For the past few years, our Christmas blogs have joyfully explored celebratory events and traditions from around the world. This year, we’re taking a fresh perspective, recognizing that Christmas can also be a time of unique challenges for many. Amid the holiday cheer, countless individuals, including mariners, continue their essential work, often in extraordinary circumstances. MAT volunteer Roger Burns dives into the history of maritime losses during the Christmas season, focusing on the southern English coast. His journey uncovers fascinating stories, including an in-depth look at one notable shipwreck.

Selected Parameters

The principal elements explored and leading to maritime incidents such as wrecks include adverse weather, navigational errors, vessel malfunction such as leakage and equipment failures, conflict, human error, and these are often in unfortunate combination. The period investigated is from 20 to 30 December between 1750 and 1950, geographically stretching along the Channel from Land’s End to Margate including the Scillies and the Isle of Wight.

Weather

Weather reports rely on diverse sources, many dating only to the mid-19th or 20th century, making it challenging to capture a full historical picture, especially for routine events. While some earlier records exist, such as digitized handwritten reports, they rarely cover the south coast or the selected period in detail.

The year 1900 was notable for having six gales with severe storms over the winter, touching the southern coast, but only one Christmas period wreck was identified, the SS Enercuri, off Dorset, on 29 December. 1927 experienced the worst Christmas blizzards in a century, but without Christmas period wrecks, and December 1929 saw excessive rainfall and gales, with 89 and 96 knot gusts respectively at Falmouth and the Scillies but on 7 December, and SS Hermine was lost on 29 December 1929 off Kent.

Coastal flooding was sometimes recorded and relatively minor occurrences were at Ryde and Lymington on 26/12/1860, with seven wrecks between Dorset and the Goodwin Sands; at Chesil Beach and around Kent and the Thames estuary on 21/12/1927 and 27/12/1947 without Christmas period wrecks. The Solent coast of the Isle of Wight was affected on 26/12/1913 with one wreck off Hampshire, as was the Solent stretching to Kent on 26/12/1924, with slightly worse flooding but without wrecks. There was significant flooding on 26/12/1912 affecting Poole, Lymington, Southampton, and the Isle of Wight through to Havant with six wrecks stretching from the Scillies and Cornwall to Sussex.

Isolated storm occurrences causing shipwrecks on Christmas Day are summarised in Figure 2 below.

Here, mention should be made of a wreck on 27 December 1852 which involved the MAT in extensive investigation, eventually identified as the Flower of Ugie with the investigation available here and dive footage here.

Wrecks

For the selected period and area, 320 wrecks either onshore or offshore were identified and these were distributed Cornwall & Scillies – 71, Devon – 45, Dorset – 33, Hampshire & IoW – 54, Sussex – 29, and Kent including the Goodwin Sands – 88.

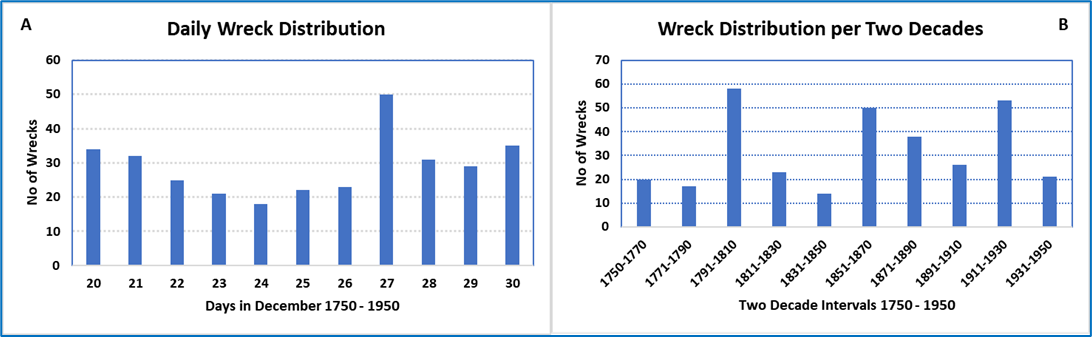

The daily wrecks, 1750-1950, for the 11 days straddling Christmas are shown in Figure 1A and over the 200 years, in Figure 1B. 22 of the identified wrecks in the decade 1911-1930 were during the First World War. The final decade included the Second World War involving 18 wrecks. These wars although contributing to the loss count did not account for all of the identified Christmas Day wrecks during the war years.

Figure 1: Wreck Distribution

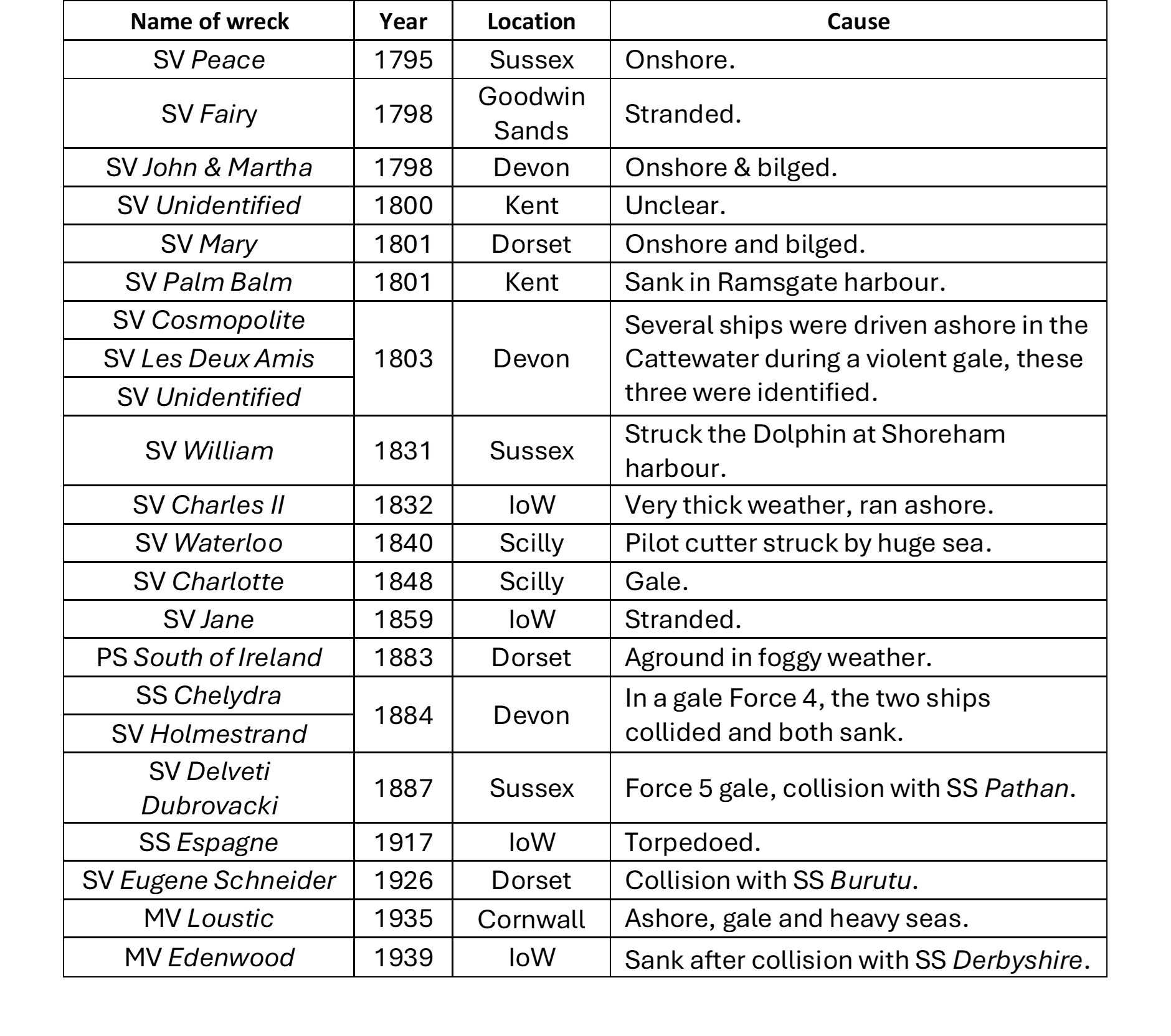

The Christmas day wrecks identified between 1750 to 1950 are listed chronologically in the following table, Figure 2, and their disposition is shown in Figure 3.

Figure 2: Christmas Day Wrecks

As can be seen in Figure 2, the Christmas Day wrecks are spread along the Channel, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: Disposition of Christmas Day Wrecks along the South Coast, 1750-1950

Sailing Vessels (SV) are coded black. Steam Ships (SS) are coded Blue

Motor Vessels (MV) are coded Green. Paddle Steamer is coded Red.

One of the above wrecks was Paddle Steamer South of Ireland which was lost in a combination of adverse weather and, as the subsequent Enquiry found, questionable navigation. The vessel’s builder built many paddle steamers between 1860 and 1875 alongside conventional steamers, and the South of Ireland was launched as an iron hulled passenger and cargo ferry on 6 July 1867 by William Simons & Co. Ltd., of Renfrew for the Milford Steam Packet Company on the Milford-Waterford crossing between England and Ireland. When launched, the vessel was credited in the media as having elegant cabins and feathering floats each side, with a description of the latter here. Paddle steamers for estuarial use were often flat–bottomed but those used later for open sea crossings had a more conventionally shaped hull to increase vertical stability and for facilitating similar immersion depths for the two paddles; without drawings, hull configuration of the South of Ireland is unclear.

Increasingly in this era as paddle steamers then steamers replaced sailing vessels for sea crossings, the railway companies offered through fares to and from distant towns via the ferries, in many locations serving England, Ireland, Wales, Scotland and France. Advertisements quoted sailing times and connecting trains, with all voyages subject to weather. Operation across the southern Irish sea was in association with the Great Western Railway who in the Spring of 1872 bought the South of Ireland and two other paddle steamers from the Milford Steam Packet Company, transferring the South of Ireland to their new Weymouth-Cherbourg route, a crossing taking between six and seven hours.

This became its well-travelled route and the only change in the vessel appears to have been the tonnage which, while under deck tonnage remaining unchanged, implied that deck cargo storage, crew and/or passenger accommodation underwent some changes over the years.

The South of Ireland was lost on Christmas Day, 1883, and intriguingly, on every Christmas period 1878 to 1882 it had encountered problems, all being machinery malfunction requiring a tow to Weymouth for repairs; in 1879 a paddle struck floating debris, and in 1882 a cylinder broke.

The ferry departed Cherbourg for Weymouth at 19.25 on Christmas Eve 1883 with 58 tons general cargo, 23 crew and one passenger. Visibility was good with a light wind enabling full speed of 11 knots but some three hours later fog was encountered and speed was halved. An hour later, the fog mostly cleared allowing full speed but shortly after more fog with half speed resumed. Just after 1a.m. on Christmas Day, the fog lifted, engines were put at full speed but just 10 minutes later in the dark, lookouts observed what they thought was a fog bank but was in fact a high cliff into which the ferry ploughed, unable to reverse in time. Once on the rocks, attempts to get off failed, so two boats were lowered to inspect the ferry externally, finding it seriously holed and filling quickly with water, so one boat with five crew was despatched to Weymouth for help. In due course, steamers arrived and the tug SS Aguila took everyone remaining off safely and with it, all the portable gear.

The wreck was initially pinned on the rocks and when visited by the tug Aguila was found to be broken in two around the fore gangway, the bows very high out of the water compared to the stern, gangways twisted, wheel house wrecked, with sea washing over the deck. Weather prevented any further salvage on the first visit. But in the following days, part of the cargo, and easily removed fittings were salved. It was hoped to save the stern section but very large pumps from Glasgow were needed and did not arrive at Portland until New Year’s Eve. These pumps, placed on a salvage barge, were proving effective on 2 January but the weather worsened and the wreck became free of the rocks on 3 January before further salvage could be undertaken. Part of the wreck must have floated some distance to its UKHO recorded position, Figure 3, which is about 150m off shore and in the line of fire from the Lulworth Army testing range. The sea is deep immediately in front of the cliffs and in 1977, there were just a few iron girders and plates, the rest scattered under the rocks and/or scattered due to tidal movement, and what was visible was heavily concreted. No further salvage was carried out.

The subsequent Board of Trade Enquiry found that the master, William Thomas Pearn, had relied on compass bearings and his route knowledge but had not allowed for the easterly flood tide and was at fault for not having taken steps to confirm his position. The Enquiry recommended his master’s certificate be suspended for three months. However, after 16 years’ service, he was dismissed by the Great Western Railway Co.

Wishing you all a happy and peaceful Christmas and a fruitful 2025!