The Flower of Ugie is a wooden shipwreck that lies in the Eastern Solent. The wreck was discovered in 2003 when a fisherman snagged his nets on a previously unknown seabed obstruction. Because the newly discovered shipwreck lay in a licensed dredging area an exclusion zone was established by the dredging company (Tarmac Marine Dredging Ltd) for its protection. Between 2004 and 2008, the MAT investigated the site as part of the Eastern SOLMAP (SOLent Marine Archaeological Project). This confirmed the location of a substantial wooden shipwreck lying exposed, just off the south-eastern edge of the Horse Tail Sands (part of the larger Horse and Dean Sands). The Horse Tail Sands is one of several treacherous sandbanks in the Solent and has been responsible for the grounding and wrecking of numerous ships throughout history.

By 2009 a significant amount of surveying and recording had taken place on the wreck. However, the precise date and identification of the shipwreck was still unknown. It was recognized that there was an urgent need to investigate the date and identity of the vessel in order to determine its archaeological significance and to develop sustainable long-term monitoring and management of the site. To facilitate this, funding from the Aggregate Levy Sustainability Fund (ALSF), distributed by English Heritage, was awarded to the project. Throughout the project the aggregates industry has continued to be involved. In particular, considerable support and input has been received from Tarmac Marine Dredging Ltd.

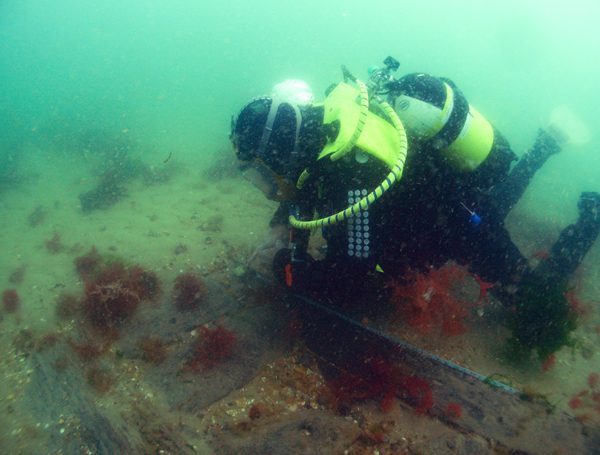

Funding from the ALSF allowed the 2009 diving season to concentrate on gathering information that would enable the wreck to be dated and identified. To achieve this, the survey of the seabed structure was completed and samples were taken from the wooden timbers and from the metal fastenings that held the hull together. This sampling process, in conjunction with careful analysis of the ship’s hull structure allowed the characteristics of the vessel to be established. Following this, historical research allowed the identification of the shipwreck to be confirmed as the Flower of Ugie. Further historical research was then undertaken that re-created the story of where the vessel had sailed over the course of its career, from building to wrecking, and allowed the vessel to be interpreted against its wider context.

Throughout the work on the site, it was observed that there were changes to the levels of sediment that covered the hull remians. The exposure of new timbers was good for understanding more about the vessel’s remains, but also meant that the newly exposed timbers then began to decay from erosion and from being eaten by marine organisms. To try to understand this process further, the wreck has been carefully monitored so that we can understand which areas of the site are losing sediment and which areas are gaining sediment.

At the same time, observations have been made about where new timbers have appeared and where older timbers have disappeared. Together, this work will allow us to plan how to manage the site in the best way in the future.

Identifying the Flower of Ugie

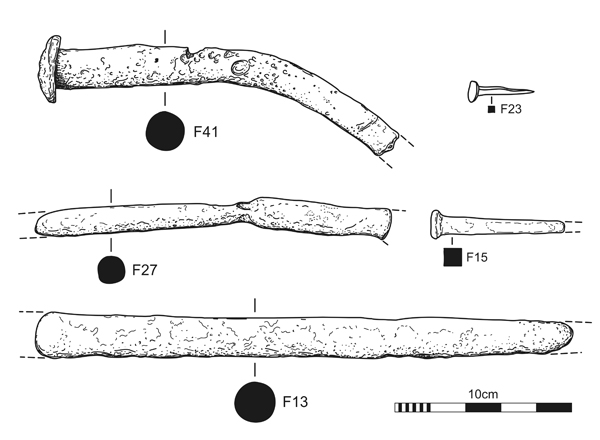

In order to complete the identification of the vessel, it was important for the characteristics of the vessel to be fully understood. This was done by careful survey of all of the remains, so that their location and size could be recorded. At the same time, important features such as the type of material used to fix the vessel together were also recorded. Both the wooden structure and the fastenings were also sampled and analysed to discover the exact material composition of them. This information helps the dating of the wreck, which allows a more precise identification to be made.

The wreck remains can be divided into three areas; a western section of hull remains, a second (eastern) section of hull remains some 23m to the east and a central area of scattered remains mainly comprising concreted elements and further wooden remains. All of the frames and planks of the vessel were built from wood, mainly Oak, Elm and Ebony. These wooden pieces were fixed together with wooden treenails (bolts) and metal bolts made from copper and brass. The vessel’s wooden structure was also reinforced with iron knees. Fragments of brass sheathing (called yellow-metal) indicated that the outside of the vessel’s hull was sheathed in that material. All of these results indicated that the vessel was built and used between about 1820 and 1860, the mixture of materials further suggested that the vessel had been refitted and repaired during the course of its life.

The detailed characterisation of the wreck remains resulting from the archaeological survey and specialist analysis allowed a general set of characteristics to be drawn up:

- The vessel is built of wood, reinforced with iron framing elements.

- The absence of mechanical propulsion elements or any significant armament indicate that the vessel was a sailing merchant ship.

- The hull is fastened using treenails as well as copper and brass bolts.

- The copper bolts are likely to have been manufactured within the UK between the mid-1820s and before 1850.

- The brass bolts are likely to have been produced during, or after, the late 1840s.

- The outside of the hull is sheathed in Muntz Metal; this can only have been applied to the hull after 1832, when this material was first patented. Analysis of recovered sheathing suggests that it dates to the late 1840s, or later.

- The vessel was probably at least 30m in length.

These characteristics were then compared with shipwreck losses recorded by the NMR, Hampshire Sites and Monuments Record, Isle of Wight Sites and Monuments Record, UK Hydrographic Office (via Seazone Hydrospatial) and the Receiver of Wreck within 10km of the wreck site. These comprised:

- 303 losses that do not have a known seabed location, only a named location (NLO).

- 77 losses that do have a known seabed location.

- Six seabed obstructions were noted within 1km of the site.

This comparison allowed the majority of the losses to be disregarded because they did not fit with the observed characteristics of the wreck. This left five vessels that required more detailed analysis; Colonist (sank 1837), Hopewell (1838), Flower of Ugie (1852), Eastern Monarch (1859) and Egbert (1867). Following consideration of their date of use, size, material composition and sinking location it became clear that the remains visible on the wreck site correlated closely with the Flower of Ugie, a barque built in Sunderland. Subsequent additional historical research into this vessel further confirmed this conclusion. Once the identification of the vessel was known, it was then possible to begin to research the career of the vessel between its building and wrecking.

Vessel History

Once the identity of the Flower of Ugie was confirmed, it was possible to investigate the building, use and eventual wrecking of the vessel, through historical documentation. This included sources such as the Lloyds Register, the Lloyds List and a range of contemporary local and national newspapers in the UK.

The keel of the Flower of Ugie was laid in August 1837 by the Sunderland shipbuilder Luke Crown. The vessel was launched in July 1838 and surveyed by Lloyds Surveyor John Brunton; listed dimensions were 102’ (31.25 m) in length, 27′ (8.23 m) extreme breadth, depth in hold of 19′ (5.8 m) and a registered tonnage of 350 old tons (402 new). The vessel was rigged as a barque. In his survey of the vessel, Brunton noted that the vessel was well built and that in some areas (such as the planking and fastening) the vessel was as good as it was possible to make. The vessel received a Lloyds classification of 10 A1, indicating that it did not need to be re-surveyed for ten years, the A categorising the hull as carrying the highest rating and 1 categorising the vessel’s rigging and stores as also the highest rating. You can view a transcription of the Lloyds Survey Report by John Brunton on the Flower of Ugie here – this document was crucial to our research into the vessel.

The sailing career of the Flower of Ugie can be divided into three distinct phases of use. The first phase saw the vessel engaged in trade between the UK and destinations in the Indian Ocean and the Far East, between 1838 and 1846. The vessel sailed to destinations such as the Cape of Good Hope, Calcutta, Madras, Mauritius, Penang, Singapore and China. This included a continuous period of three years without returning to Britain, when the vessel sailed mainly between India and Mauritius. It is likely that the vessel was involved in the transport of indentured labour from India to the island of Mauritius during this period. The second part of the vessel’s career began in 1847 and correlates with a change in ownership. In this period the vessel remained in the northern hemisphere and visited destinations in Europe and North America. The ports visited included Odessa, Constantinople, Alexandria, Hamburg, Bremen, St Petersburg, New York and Quebec. A third phase of use occurs at the end of the vessel’s life, during 1851 and 1852 and is a combination of the first two periods. This again sees the Flower sailing to destinations in South Asia (Sri Lanka and Burma), as well as returning to North America (Quebec). The final intended voyage of the vessel was from Sunderland to Cartagena in Spain.

The Flower of Ugie departed Sunderland on 7th December 1852, bound for Cartagena with a cargo of coal, passing Deal on the 22nd December. On the 26th December the vessel encountered a severe storm in the English Channel and was thrown on its beam-ends (turned on its side) off Portland. The main-mast and mizzen-mast were cut away in order to save the ship and bring it upright again. Following this, the damaged vessel arrived in the relative shelter of the eastern Solent in the early hours of the 27th December. It was reported as having thirteen feet of water in the hold. The Flower of Ugie became stranded on the Horse Tail Sand and the foremast was cut away in order to try to stabilise the vessel. The captain and crew were eventually forced to give up their attempts to save the vessel and they abandoned ship, reaching safety in an attendant pilot boat. Observers report that the vessel broke up rapidly and sank during the afternoon of Monday 27th December. Some elements of the vessel’s rigging that were washed ashore were sold at auction a few weeks later.

Flower of Ugie interpretation

The Flower of Ugie was built on the banks of the River Wear in 1838; fourteen years later the vessel was wrecked in the Eastern Solent. Between these two events the Flower spent the vast majority of its life at sea, sailing thousands of miles between a range of ports in South Asia, Southern Africa, Europe and North America. In this sense the vessel epitomised the age of global seafaring and developing capitalism that was in full-swing by the mid-19thcentury.

Although unclear, it seems likely that the vessel was commissioned for use in the trade with British colonies in Southern Africa and South Asia; the Cape of Good Hope, Mauritius, Madras and Calcutta being primary destinations over a number of years. With this in mind, it may be possible to classify the Flower of Ugie as a late form of British East Indiaman, albeit one with no connection to the British East India Company itself. Ascribing such a status to the Flower of Ugie is perhaps over-simplistic; the vessel was very much the continuation of a tradition of British merchant shipbuilding that could be traced back to the beginning of the 19th century. If shipbuilder Luke Crown had been engaged in the building of a similar sized vessel, but with an intended destination of Quebec, rather than Calcutta, it is likely that he would have built the same design of vessel with the same materials and carrying the same rig. The flexibility of the ships resulting from the building tradition in which the Flower was constructed is illustrated by the range of destinations and variance in passage distance that the vessel was capable of being employed on. The vessel was equally suited to trade in the Baltic or Mediterranean as to the conveyance of cargoes to the East Indies.

In light of later developments in materials and hull-form, in particular iron and steel and the clipper-style hull-form, it is easy to view the Flower of Ugie as being at the end of a particular branch of shipbuilding evolution. While this may be true in part, this should not mean that the vessel is viewed as backwards looking, low-tech or less advanced. Consideration of why the Flower of Ugie was constructed in such a way, and using such materials, provides a clue to the motives of the builder and owner and offers another interpretation of the vessel. The Flower was built to a tried and tested design formula that offered the capacious, steady conveyance of cargo over potentially long-distances in an economic fashion. Further indication of the latter is given by the rig of the vessel, selected for economic performance, rather than out-and-out speed. The building materials tell the same story through the building and repair of the vessel during its career; materials selected because they represent the most cost-effective way of achieving a specific technological aim.

Taking all of this into consideration, it is possible to see the Flower of Ugie as representing a state-of-the-art approach to the procurement, use and deployment of materials in a manner in which economics was the primary driving force. Viewed in this way, the Flower of Ugie does not lie at the end of a technological line of development for large wooden shipbuilding, waiting to be displaced by bigger, faster iron and steel vessels; the fact that vessels such as the Flower of Ugie would cease to be built within a generation of its launch is beyond question. But Luke Crown could not foresee this in 1837, he was simply building within the accepted tradition of the day. Instead, the Flower of Ugie may be seen as representative of the pinnacle of British wooden merchant shipbuilding, developed over several centuries and epitomised in the approach of shipbuilders in the north-east of England and in Sunderland in particular.

On a wider-scale, the Flower of Ugie also symbolises much more than simply a technological snap-shot of British shipbuilding in the mid-19th century. The role played by the vessel throughout its life places it at the heart of the globally developing trading systems that were an on-going feature of the 19th century. Many of these routes and the goods, people and ideas that travelled along them, lay at the heart of British commercial activity at this time. This activity itself was linked irrevocably with the development of overseas colonies and the maintenance and expansion of the British Empire during the 19th century. In this sense, the Flower of Ugie is itself the result of this activity as well as a facilitator of its continuation. The technological features of the ship are simply the tangible manifestation of 19thcentury commercialisation, colonialism and economisation.

Management & Monitoring

In the course of the work conducted by MAT there has been continual degradation of the site in addition to the on-going exposure of new timbers. Understanding how the sediment that covers the site is changing is important. The layer of sediment buries the ships wooden timbers and provides protection from erosion and from marine organisms such as shipworm, which can rapidly eat and destroy any exposed timbers. An effort has been made to understand this important element of the site’s future management in three ways.

- Wider-scale assessment of the geophysical data, kindly provided by Tarmac Marine Dredging Ltd, and historical mapping of the Horse Tail Sand.

- Installation of monitoring points across the site that can be checked every year to assess whether or not there has been a change in sediment in that specific area of the site.

- On-going observation of the structural remains of the site to record where new timbers are appearing and to record if any existing timbers have been lost, either through decay or human interference.

The first component illustrates that over the last 15 years there has been a steady but gradual loss of sediment across the entire area of the site. It seems that sediment may be moving from the sandbank itself into the dredging holes left from old dredging, that lie to the south of the site. This work has been combined with analysis of the historical location of the Horse Tail Sand. The dynamic nature of this sandbank means that it moves around over time and it is possible to observe the different locations of the sandbank on historical charts dating back 150 years. This has shown that since the wrecking of the Flower of Ugie the Horse Tail Sand has moved to the south, this trend now seems to have reversed and the sandbank seems to be moving slowly to the north. These two factors probably account for the on-going exposure of the shipwreck remains.

The second comment involves monitoring the sediment levels at specific areas of the site. This work was only started in 2009, so measurements only exist for the 2009 and 2010 seasons. This has produced quite a mixed picture. Despite the overall sediment loss across the site, there are some areas where there has been an increase in the sediment levels. The continuation of this work over the next few years should indicate exactly how the protective layer of sediment that has covered the site is changing. Finally, the third area of work has recorded changes to the amount of exposed timber since the MAT began working on the site in 2004. This has shown that while the western section of the wreck has survived in nearly the same state, the eastern section has suffered from a much greater loss of wooden material. At least some of this has probably occurred because of fishing nets getting caught on the site in the period after the site was first exposed. One of these net snaggings led to the site being discovered in the first place.

The long-term future of the wreck site is not clear. The geophysical and historical chart analysis, in conjunction with the initial monitoring work has shown that there is gradual, yet on-going sediment loss taking place across the site, with a few areas of sediment accumulation. The loss of sediment leads to the exposure of new timbers and structural elements. Once exposed, these begin to decay as a result of the effects of underwater erosion and attack by marine organisms. The only way these two processes can be halted is if the levels of sediment on the site increase, leading to the wooden structure becoming buried once more. The effects of erosion and degradation by marine life can never be reversed.

Although the majority of the research into the Flower of Ugie has been completed, there are still obvious areas for on-going and future work. Monitoring of the site will continue, in doing this our understanding of site-formation processes on wreck sites in general will increase, as well as keeping track of the changes that are happening to the Flower of Ugie. In addition to this, although much is known about the building, sailing and wrecking of the vessel, there is still much more to be discovered about the cargoes, people and crew of the vessel. This research should provide a fascinating insight into the lives of seafarers during the mid-19th century.