People have always needed to move around the Solent area, using the watercraft available at the time. From the logboats of the Mesolithic times, to multi-decked sailing vessels of the Middle Ages. In this blog, volunteer John Davies shows the development of these watercraft, some meeting their final resting place in the Solent, others only passing through.

Log boats

The earliest known form of watercraft was the log boat, also known as the dugout canoe. These evolved in many parts of the world, at different times.

Following the end of the Ice Age around 12,000 years ago, sea levels began to rise slowly, covering the northern European land and forming the southern North Sea and English Channel. This meant that prehistoric tribes in those areas needed to move and had to develop some means of crossing, or travelling along, rivers and coastal waters. By about 8000 years ago, the Solent was forming, but not completely open at the western end of the Isle of Wight.

In Neolithic times, on the northwest shore of the Isle of Wight, a local tribe began making a log boat. They used tools made of flint and antler to shape the outside of the boat. To hollow it out, heated stones were placed on the wood, which burnt out the centre, final shaping and thinning was done with flint scrapers. However, the boat seems to have been unfinished and abandoned, as sea levels continued to rise and the area to become more silted and marshier. It was not to be discovered for about 8000 years, when a fishing boat brought up worked flint tools in the 1960’s. Investigations by divers over the next 30 years revealed a submerged, eroding cliff, Bouldnor Cliff, about 11m below mean sea level, and a large area of tree stumps. Later dives uncovered sections of worked timbers suggesting a boat several metres in length, but much of it had eroded away.

The construction of log boats continued for millennia, with examples found around southern England from various dates. There is an Iron Age boat (around 1000 BC) in Poole Museum, one found in Langstone Harbour dated to about AD 500 and one discovered in the River Hamble near Fairthorne Manor. The latter was carbon dated to AD 800 and is about 4.1m long x 0.75m beam. This date corresponds with the origins of the Anglo Saxon settlement of Hamwic on the west bank of the River Itchen, in the area now known as Chapel / St. Mary’s.

Coracles

These small, round, portable craft were used throughout much of the southwest of England and Wales, mainly for fishing. No remains of one has been found in the Solent area, but, being so flimsy, would have quickly disintegrated, so it cannot be said that that they did, or did not, appear in this area.

Figure 1: Image of a modern coracle (above) and a dugout canoe (below) at the Shipwreck Museum in the Isle of Wight

Plank-built boats

In the Early Bronze Age, the plank-built boat was a development of the log boat, to provide greater size and sea-worthiness. Felled trees were split with wedges into parallel planks and the edges trimmed using axes or adzes. Early tools were of bronze and later ones of iron.

The planks were pierced close to their edges so that adjacent planks could then be sewn together using hide strips or hemp cord. The joints were than caulked with moss and animal hair. In later boats, the planks were fixed to wooden frames along a keel with iron nails.

Boats of this type were found in various parts of England: three at Ferriby, Yorkshire, also at Kilnsea, and Caldicot. These were constructed between 2000 and 1000 BC and had a flat bottom of broad planks, whilst the sides were of curved clinker construction.

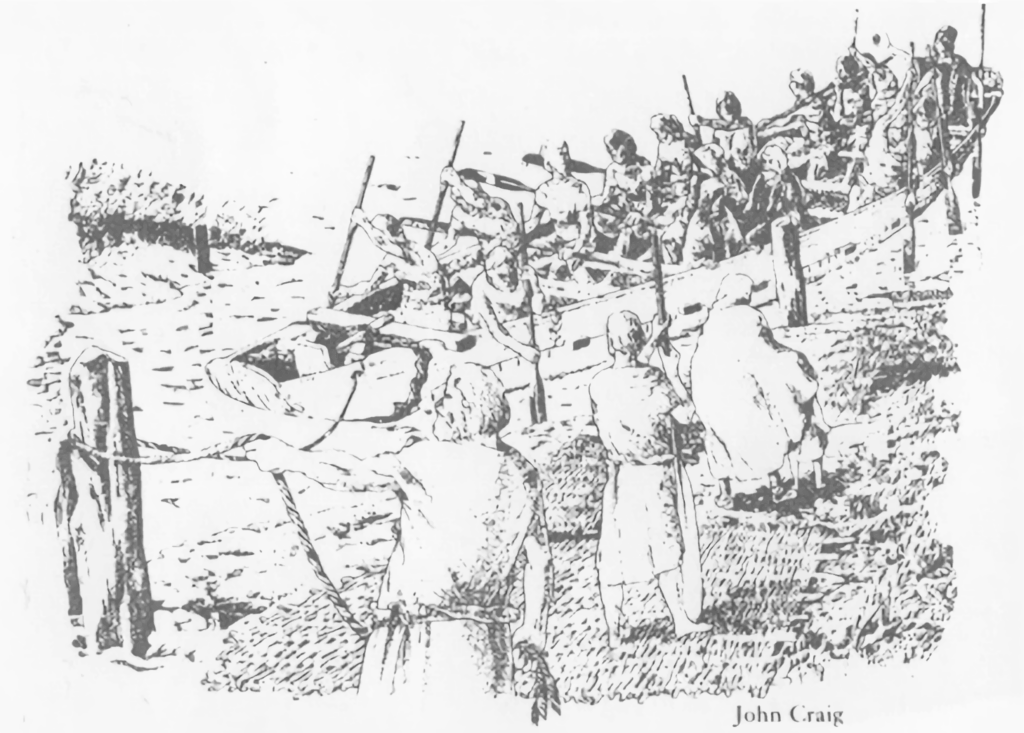

Figure 2: A Ferriby boat (The Story Beneath the Solent: Discovering Underwater Archaeology, Hampshire and Wight Trust for Maritime Archaeology, courtesy of John Craig).

A 9th Century boat was found at Graveney, north Kent. This was 14m long and nearly 3m beam, with a keel and planking curved into stem and stern posts. There was no evidence of a mast, so it was probably propelled by oars. Such a vessel could well have come around the south coast to the Solent, but there is no firm evidence to confirm this.

Pre-Roman boats

In the few centuries before the Roman invasion, boat-building techniques on the Continent had evolved into quite sturdy vessels. In Caesar’s history Gallic Wars, he described Gallic vessels as being different to Roman ones. They had very high bows and sterns for use in heavy seas. Their hulls were made of oak and fastened with iron nails. Some of their timbers were over a foot wide.

No remains have been found in the Solent, but there is much evidence of trade between northern France and southern England, including at Hengistbury Head.

Roman vessels

Following their successful invasion in AD 43, the Romans spread across southern Britain, establishing settlements and forts. In the Solent area, these included Portchester, Clausentum (Bitterne Manor, Southampton) and Venta Belgarum (Winchester). These all needed supplies and trade to and from the Continent. As the Romans were here for around 400 years, they would have had a lot of vessels sailing between Britain and the Continent. There were three main types of vessels in use: Liburna, Corbita & Oneraria.

Liburna

This boat was mainly a fighting vessel, with a single row of oars, a main mast with a square yard & sail and a foresail carried on a forward-inclined mast. Steering was with a large oar on the starboard side at the stern. Some of them had the bow formed into a ram. It is probable that this type of boat was used in the invasions.

Corbita and Oneraria

These were standard freighters of varying sizes, with a main mast and square yard/sail and a small foresail, but they appear not to have oars. They carried cargoes of oil, grains, etc. in terracotta pots or amphorae into Britain and returned to the Continent with loads such as wool, tin and copper. They were usually up to 35m length and almost 10m beam, often built of oak. (Larger ones in the Mediterranean have been found up to 55m x 14m capable of carrying 2000 tons of cargo). Remains of Roman pottery and other artifacts have been found on the Isle of Wight and many locations in southern England, showing extensive trade with the Continent. No remains of these vessels have been found in the Solent area, although three have been found in London dated to the 2nd and 3rd centuries.

The Romans invited the Angles and Saxons to Britain to help them fight the Picts around the end of the 4th century, following which the Romans were ordered to leave. So began the Anglo-Saxon era, which saw the gradual development and improvement of ship design.

Viking longship

In AD789, Viking raids began with an attack at Portland, Dorset, followed over the years by raids on numerous settlements around the English coast, including the Solent.

These were clinker-built vessels without a keel, about 20m long, with a stempost enlarged to a dragon’s head. They had a mast and square sail, as well as oars. In the Early Middle Ages, the knarr was a development of the Viking longship as a cargo vessel, being larger and with a bigger square sail on a central mast. They were about 16m long and 5m beam and could carry up to 25 tons of cargoes such as wool, furs, wheat, timber and even livestock.

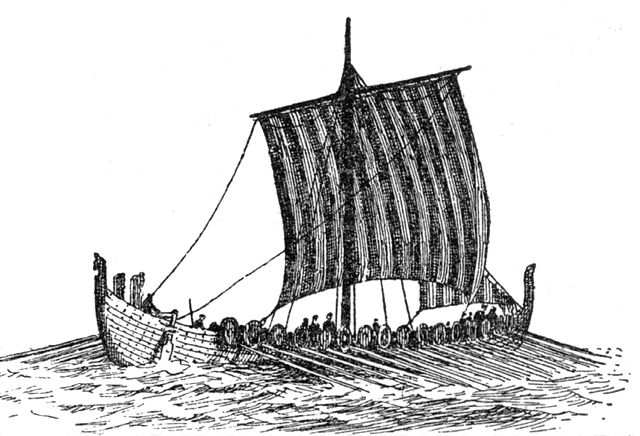

Figure 3: A Viking longship (Wikicommons)

Figure 4 :Knarr (Wikicommons )

In the High Middle Ages, three types of ship evolved; the keel, the cog and the hulk:

Keel (anglo-saxon: “ceol”)

The keel was a clinker-built vessel with a full length base timber and clinker-laid planks fixed to frames attached to the base (now known as the keel). One or two masts with square sails on yards.

In AD 896, the Anglo Saxon Chronicle recorded that King Alfred (based in Winchester) had built a new fleet of 60-oared warships. These were of the clinker-built Keel type and probably spread around southern and eastern England, with some in the Solent. No remains yet found.

Cog

The cog was of Danish origin, but traded widely with eastern and southern Britain, likely including the Solent. It had high, steep clinker sides with straight stem and stern posts and a flat bottom, with similar masts and sails. The length was between 15 and 25m and the largest could carry up to 200 tons of cargo. They have been described in documents from the 9th century but no remains have been found in the Solent.

Figure 5: A cog replica (Wikicommons)

Hulk

The hulk was also clinker-built, with high stem and stern. Masts and sails were also similar to the keel. This type of vessel was referenced from around AD 1000. Their appearance has been deduced from depictions on town seals and the like.

Norman French ships

After the Norman invasion and the Battle of Hastings in AD 1066, French vessels such as the carvel-construction carrack would have appeared in the Solent. Their appearance can be seen depicted in the Bayeux Tapestry, but no remains have been found in the Solent

Grace Dieu

By the Late Middle Ages, ship design and construction had evolved to the extent that a significant warship, the Grace Dieu was ordered and built in the early 15th century. It was an English version of the carrack and was completed in 1418. Weighing in at 1400 tons displacement, it was the largest ship of the time and approximately 50m long, with triple-layer planking. Accounts record the use of 1000 beech trees and 17 tons of iron nails.

It was in service from 1420 for ten years, but made only one voyage in that period, by which time England had control of the sea along the south coast. Then, in 1430 it was taken up the Hamble and moored. Four years later, it was struck by lightning and burned down to the waterline. It’s remains lie in the mud of the River Hamble to this day and can be found on a map visible here (HAM052).

Some fragments of these vessels can still be seen around the Solent area, such as the Hamble log boat (now in a Southampton Museum store), another in Poole Museum. Also, the remaining parts of the Grace Dieu can sometimes be seen in the Hamble at Low Water Spring Tides. It is possible that remains of Roman, French and later ships may yet be found around the shores of the Solent.