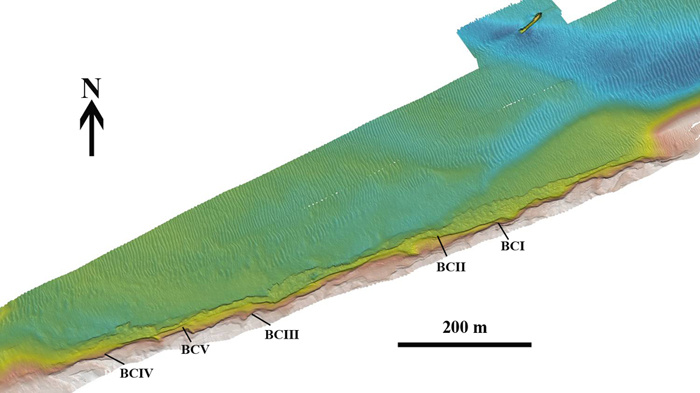

The submerged Mesolithic landscape at Bouldnor Cliff lies on the edge of the drowned palaeo-valley and is now 11m underwater, 1km east of Yarmouth on the Isle of Wight. It stretches for a further kilometre west to east and contains five known loci containing archaeological evidence. It lies within the Solent Maritime Special Area of Conservation and is in the Yarmouth to Cowes candidate Marine Conservation Zone.

Work on this fascinating prehistoric site began back in the 1980s, when it was identified as a preserved prehistoric forest with associated peat deposits.

However, it wasn’t until 1998 when the Hampshire and Wight Trust for Maritime Archaeology (now the Maritime Archaeology Trust) began investigating the site as part of the European ‘LIFE’ Project that research began again. During a routine survey dive volunteers spotted interesting worked flints in a lobster burrow. Excitement grew as more worked flints were found over the duration of the fieldwork season in 1998 and 1999. During the 1999 season a full profile of the cliff showing the multiple layers of peat and alluvial silts was compiled.

Since then work has been ongoing throughout numerous fieldwork seasons, during which more fascinating discoveries have included worked and burnt flints, hearths, wooden ‘platform’ structures and a worked wooden artefact that could be part of a log boat or trough. Excavation and rescue recovery have been completmented with palaeoenvironmental analysis and radio carbon dating. This data has provided additional context for the site and erosion studies, which have demonstrated how fast it is disappearing.

Significance

Bouldnor Cliff is made up of several smaller sites. Two of these are particuarly archaeological productive, and have been dated to c. 6,200 to 6,000 cal BC. One has been the source of almost 1,000 worked flints, flakes, and tools, while the other, with close to 100 pieces of worked wood, has practically doubled the amount of Mesolithic worked wood in the UK. Sedimentary ancient DNA from the sites has revealed a habitat of oak forest and herbaceous plants, inlcuding Einkorn: this last find provides evidence that wheat arrived in Great Britain over two millennia earlier than previously recored.

Bouldnor Cliff is the only archaeological site in a submerged Mesolithic landscape currently known in the UK. The waterlogged anaerobic conditions have created an excellent environment for preservation for organic material. Consequently, the site has the highest potential for the best-preserved discoveries of Mesolithic artefacts and palaeo-environmental evidence in the UK, as has been demonstrated with the unique DNA, boat building and string finds mentioned above.

Internationally, the findings suggest a sophisticated Mesolithic site with social networks linked the Neolithic front in southern Europe or the north European plain. These were some of the last people to cross from the continental landmass to Great Britain before the formation of the North Sea. Interpretation of the results would help us understand the potential and character of international connections and help us locate comparable sites within the submerged palaeo-landscapes that are being discovered across the British and European Continental shelf. Unfortunately, the evidence has been located because the seabed is eroding. Monitoring over a ten-year period has recorded lateral erosion of up to 4m in the most vulnerable parts of the archaeological sites.

A Mesolithic World

Environmental specialists have been analysing pollen, plant and insect remains. Their work has revealed a changing environment which saw pine replaced by an oak/hazel woodland, with alder probably fringing the rivers and streams.

Hazel nuts, which had been nibbled by rodents and terrestrial insects, were amongst the remains, and the deposit also contained carbonised hazel nut fragments and oak charcoal. This is significant as waterlogged hazel nuts are the food waste of rodents, whereas carbonised nutshell fragments relate to human occupation activity. This discovery is quite exciting as Mesolithic food remains in southern England are rare.

The site sedimentological characteristics suggests that the habitat was once located next to a semi-stable river bar. Based on the evidence we have found so far, we believe that the sites were used as seasonal camps or more semi-permanent habitats during the Mesolithic. We also know that this was an extensive settlement area, as we have found archaeological material stretching across the coastline for several hundred metres. The dating of the artefacts also concludes that the whole area was occupied (consistently or repeatedly) concurrently around 8000 to 8200 years ago.

Analysis of the sediment’s characteristics represent changing vegetation with conditions becoming wetter. The diatom assemblage show brackish water, salt marsh or mudflat habitat before complete marine inundation occurred.

Of the flint pieces (lithics) discovered, more that 40 are struck flakes in a remarkably fresh and sharp condition. The knapping process shows evidence that it was carried out with the aid of an antler or bone hammer, a technique confirmed by Phil Harding’s (Time Team) experiments in replicating the flint industry at this site. The sharp edge blades also have signs of re-use. A surprising discovery was that of the tip of a flint axe displaying a uniform and bifacially prepared cutting edge similar to axes of Neolithic type (2000 years later); this is an unusual occurrence in a British Mesolithic context.

Under Threat

After monitoring the Bouldnor Cliff site since 1999, it has become apparent that the site is seriously affected by coastal erosion. Every year more of the site becomes exposed. This puts the archaeological material under the threat of being washed away before it can be recorded, and thus important clues could soon be lost. Where the organic material (e.g. wood) has been well-preserved in the silts on the seabed, the exposure to oxygen will quickly cause the material to degrade. Losing the submerged forest and root system will also accelerate the speed of erosion, as it allows for the sediments to be simply washed away.

The threat of erosion at Bouldnor Cliff was recently highlighted in a blog post by Historic England. The Mesolithic site is listed as one of 7 key archaeological sites that are currently under threat of eroding fast. The Trust is currently only able to conduct a rescue mission of the material that has already been exposed. In order to be able to continue rescuing archaeological material and conduct further excavations before the site is lost, we are appealing to the public for help. Please donate here to help save Bouldnor Cliff. Thank you for your support!

More Information

For more in-depth information we have compiled a research report (2011): “Mesolithic Occupation at Bouldnor Cliff and the Submerged Prehistoric Landscapes of the Solent”. More information on the book, and where to purchase it, can be found here.

You can also view all of our 3D models of the site and some of the worked timbers below.

Ongoing Research

The site of Bouldnor Cliff is regularly dived, monitored, and researched by the MAT. You can find out more about each season’s discoveries below:

2000 – 2002

Peat deposits gathered and analysed in previous years allowed a date to be put on the site of Bouldnor Cliff. This date, whilst broad, put the site firmly in the Mesolithic period, specifically to sometime around 6,000BC.

With this background, a large scale investigation was mounted in 2000. This work brought together a team of professional diving archaeologists and volunteers on a boat moored over the site for 7 days. Divers on ‘Surface Supplied Diving Equipment’ (SSDE) and the more mobile ‘Self-Contained Underwater Breathing Apparatus’ (Scuba) divers were both employed to investigate the site below the surface; the SSDE divers could have longer on the seabed with full communications to the surface while excavating, whilst the Scuba divers were able to track the peat deposits to the east and west of the site.

Sections of the seabed were removed in specially designed trays; these were then excavated on the surface under controlled conditions. Undertaking this more detailed investigation of the deposits above the water has ensured a high recovery rate for the many worked flints.

In addition to the excavation of stratified deposits, further investigation of the underwater landscape was carried out to map the extensive peat layers which run for over a kilometre at a depth of 11m. Another task was the sampling of the remains of the Mesolithic forest which lies in the lower peat deposit; these are being subjected to dendrochronological analysis.

The 2002 season targeted three sites for further work. Two lay to the west of the ‘main’ Bouldnor site and one to the east. They all exhibited the features of three peat horizons, a vertical profile and surfaces suitable for monitoring. The easterly site was the most interesting, showing the basal peat deposits thinning out at various levels up the cliff. Further worked flints were also discovered on the land surface below the peat.

2003

Funding from English Heritage in 2003 allowed further excavation of the submerged landscape at Bouldnor Cliff. The opening up of an extended trench by divers using surface supply equipment early in 2003 permitted the new exposures in the trench to be sampled.

The newly exposed stratigraphic layers were exciting but suggested a complicated sequence of events. The lowest exposure contained fluvial gravels within sand and flint fragments. A small cluster of burnt flints were recovered from above this horizon which suggested burning and possibly a hearth. A silty sand layer above this contained freshly knapped flints.

Bulk samples were taken and also samples using specially constructed monolith tins which were subject to dating and specialist analysis. The specialists analysed pollen along with macroscopic and microscopic organisms in the sediments, which can help interpret past environmental and climatic conditions. These results could then help to reconstruct events which shaped the geomorphological evolution of the Solent.

The discovery of this Mesolithic site below the waterline outlined the need to look for other such sites beneath the sea. The sea level has risen by as much as 100m since the Mesolithic period in some areas around Europe, so these sites will long have been hidden from view. The investigations at Bouldnor can help us assess where best to look for other sites in the future.

2004

Late in 2004 an exciting discovery was made by MAT divers inspecting the site. A pit containing worked flints was lying within the ancient land surface. Additional material at the site included a worked flint embedded in a sapling exposed on the cliff face. The feature was located 2 metres to the west of the hearth and 30cm below the Mesolithic submerged forest. Adjacent to the timbers burnt and worked flint was exposed in the cliff face. The site predated the inundation that formed the landscape.

Support from SCOPAC and BAE Systems enabled MAT divers to visit the site on several occasions in 2004. Samples were collected in monolith tins which were assessed for pollen and environmental evidence, and a branch from the archaeological horizon beneath the Mesolithic forest level was sent for C14 (radiocarbon) dating.

On-going inspection by divers during the summer of 2004 showed this area to be rapidly eroding. The excavated pit site was protected with sand bags, but this could only be a temporary measure. The confirmation of this rapid erosion demonstrated that there was a need for urgent action to recover what remains of this unique discovery, before the information contained in this non-renewable resource is lost forever.

2007

During the 2007 fieldwork season, Mesolithic wooden artefacts, flint tools, reused burnt flint, worked wood chippings, charcoal, and timbers covered in tool marks were some of the items recorded and recovered from the site. Evaluation trenches revealed an area rich in evidence of Mesolithic life that suggested industrial activity, with evidence of woodworking and burning. The discoveries not only revealed the stone tools used by prehistoric people to fashion items necessary for daily living, but also the organic articles they crafted.

Attention was first drawn to this specific site following discoveries in the autumn of 2004 when a burnt-flint filled pit was spotted eroding from the edge of the cliff. The pit, believed at first to be a deep hearth or oven, lay adjacent to a timber built platform-like feature. The discoveries were sampled and dated as part of an English Heritage project.

Monitoring the features over the last three years indicated the cliff and seabed were steadily retreating, removing anything archaeological with it. Exposed timbers that were recovered from the surface of the seabed for examination proved to be too degraded for interpretation. Biological erosion, ably assisted by a two-knot tide, quickly removed detail, leaving items peppered with pitted surfaces and impregnated by holes an inch in diameter.

It was clear that an evaluation excavation would be necessary in order to identify the potential of the site and to recover information before it degraded. A project was therefore developed to investigate the archaeological landscape and was funded by the Leverhulme Trust via the Department of Archaeology, University of York and by the Royal Archaeological Institute.

Project Preparation and Fieldwork

Preparation for the excavation began in May when the site grid was set up. The greatest challenge presented to the MAT excavation team was the recovery of delicate archaeological and palaeo-environmental material from the seabed, whilst minimising the impact on its integrity. To achieve this and to assess the broad distribution of material, the area first needed to be defined, so a grid was established on the seabed as a framework for recording. Markers were placed at set intervals within the grid along the cliff to act as reference and monitoring points to inform future changes. The next step was to identify sections within the grid for detailed survey. A uni-strut frame, courtesy of Analytical Engineering, was fixed over the test pits before layers were removed to record stratigraphic horizons.

June saw the first tranche of augering, which helped characterise the stratigraphic layers. This was led by the Defence Diving School from their tender with help from Andy Williams with his RIB Dingle. In July and August, two busy weeks of diving activity saw the extensive survey and recovery of samples from the boats Wight Spirit, Oberon, the Ro Ro Sailing Project catamaran Scot Bader, and Rob Heaton’s RIB. For these two weeks a shore base was established in Keyhaven Scout Hut, which hosted a total of 29 volunteers who came from as far away as Canada, Australia, France, Newcastle and York. While the work was hectic and lasted from dawn till dusk, the volunteer and professional divers were supported by the shore crew who provided excellent catering, as well as excavating, sieving and sorting through the many samples retrieved.

An alternative method used to maintain contextual integrity was to sub-divide areas and retrieve cohesive samples sequentially. The sample boxes had been designed in-house with the aid of construction specialist Bob Bailey. In total 43 samples were recovered from the seabed; the holes left behind were subsequently back filled. Excavation and sieving of the material in the sample tins recovered from the site uncovered numerous artefacts, including worked wood, worked flints, burnt flints, charcoal, wood chippings, hair-like fibres and a wide range of immaculately preserved macrofossils.

In addition to the samples raised within the tins, larger pieces of timber were excavated to the south of the site and recovered in lifting baskets. These included posts, stakes and plank-like timbers.

Overall, the project preparation, fieldwork and post processing (which was conducted at the National Oceanography Centre) covered a period of over nine months. A total of 18 diving days involving six boats and 45 people helped to recover the material from the site. The project owed its success to the great number of people involved. This included professional archaeologists, the Defence Diving School, students of archaeology, avocational divers, volunteers (above and below water) and of course the many people who support the work of the MAT. Finally, this ground-breaking work would have proved very difficult without the amazing dedication of all the volunteers.

Interpretation

Initial interpretation of the findings suggested industrial activity, where flints and pebbles were used to prepare timber by burning it before it was cut. The flints were repeatedly heated to a high temperature and appear to have been stored in at least one pit before being reused. Amongst the finds was a pointed stake, a large piece of round-wood with cut marks and a timber 60cm wide and over 1m long. These large pieces of timber have yet to be fully analysed, but appear to be intrinsically linked by the nature of their immediate relationship. Any structure that requires such large components demonstrates a considerable amount of investment of time, which in turn implies a degree of local settlement.

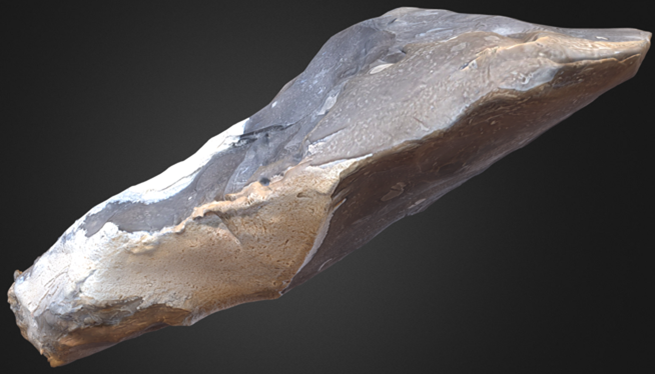

The largest timbers appeared to have been hollowed out in the same way that a log boat or trough might be made. The evidence for burning, flint heating and wood working would also be what was expected from a site where such artefacts were made; the hot flints would be used to carbonise the wood which could then be more readily removed from the centre of the tree trunk with stone tools.

Other timber raised from the seabed in October 2007 appeared to be the remains of a single piece of wood that had deteriorated prior to becoming protected by fine fresh water silts, an event that occurred prior to the rise in sea level.

The largest of the timber fragments was 94cm long by 40cm at its widest point and its maximum thickness was 3cm. It was found protruding horizontally from a small cliff. Sediment had covered and protected it but its original length remains unknown as it had been truncated by recent erosion. Initial inspection suggested the wood was hollowed out along the grain.

Directly beneath the timber was a layer of twigs and small branches; these did not show evidence of burning. Amongst this layer were the remains of hazelnuts, one of which appeared to have been sprouting shoots. This provided further evidence of stabilisation before the area became inundated and submerged. Below the twigs was a dense deposit of charcoal 2 to 3cm thick with a scattering of burnt flints, followed by further layers of twigs and charcoal. These multiple phases of burning activity suggest it was an area that was occupied for a period of time rather than a one off encampment. It also infers there could be much more material to be found which deems it important to recover this before it is lost.

2008

As well as processing of the assemblage recovered in 2007, 2008 saw on-going fieldwork at Bouldnor Cliff. Divers located a further 31 worked flints, mainly from newly eroded areas at BCII. A series of auger samples were collected from BCV where more timbers associated with the possible log boat were found. Another loci of archaeological finds was discovered eroding from the cliff 100m to the east of BCV.

The work on the site in 2008 continued primarily with the support of the Leverhulme Trust and the Royal Archaeological Institute who provided grants to push forward investigations on this unique resource. It is an area that has a lot more to offer within the pristine land surface buried below the silts. Unfortunately it is a race against time as the ongoing loss of the submerged prehistoric landscape means the loss of an unparalleled component of our prehistoric heritage.

2009

Following previous years’ work, which saw a range of survey, sampling, excavation and analysis work undertaken, the work in 2009 concentrated on rescue survey and recovery of ‘at risk’ items from this important Mesolithic site. An inspection dive in June revealed that erosion and trawler damage was evident on the seabed.

More timber was being exposed on this nationally important site. One particular worked piece was protruding 20cm from the archaeological layer. The wood was adjacent to the section recovered in 2007 and believed to be associated with it. The exposed section of timber, which had been cut to a point, was rescued.

Further investigations of the site were undertaken during the first week of July. The dive team worked hard to record the site including planning, excavating and filming the activity, resulting in an invaluable archive that will help illuminate our knowledge of the southern British Mesolithic environment.

In July the sondage (small test excavation) cut in 2007 was extended to include the area around the newly exposed timber above. Removal of the covering sediment revealed a wide array of interconnected pieces of what appeared to be trimmed oak members measuring between 8 and 14cm wide. The length of the pieces is as yet unknown as they continue into the bank. The complex of timbers suggests that a substantial Mesolithic structure had once stood in this location.

Later in July, Channel 4 joined the MAT team for a day’s diving on Bouldnor Cliff to carry out filming for a four-part series: Man on Earth. Tony Robinson travelled back through 200,000 years of human history to find out what happened to our ancestors in the face of catastrophic climate changes. The MAT featured in the second episode, The Birth of Civilisation, shown on Monday 14th December 2009.

2010

Fieldwork during 2010 focused on the recovery of strategic samples in order to resolve inter-related parts of the buried worked timbers. In addition, the development of a functional monitoring system was continued. This valuable work is being supported by the European Regional Development Fund through the Atlas of the 2 Seas project and the COST programme through the SPLASH-COS project.

The week of fieldwork was undertaken by a team of professional divers and volunteers. With the help of three boats and a team of 12, the work concentrated on and between the locations at BCII and BCV. The positioning of monitoring pins every 25m along a 400m stretch between the two sites was one of the key tasks begun in 2010. The system is made up of labelled monitoring pins allowing divers to locate positions underwater while acting as reference points to monitor cliff erosion. The pins were marked with small fishing floats to facilitate location in the future. Neap tides, when the tidal range is lowest, were used to maximize working time underwater which was forever being curtailed by relentless tidal changes. This was particularly restricting when it came to checking the monitoring pins which necessitated the divers swimming back and forth against the moving water.

The work on BCV was focused on an area where previous excavations have revealed worked wood. The area was planned in 1:20 and a couple of monolith box samples were recovered. Further pieces of worked wood were identified and rescued for laser scanning by the University of Birmingham. The work on the area of BCII focused on collecting samples and recovering surface finds of flints.

The dive team was supported by an eight person shore-side team made up of MAT employees and experienced volunteers who processed all the samples recovered by the divers on a daily basis. Volunteers began the week identifying and sorting through lithic samples recovered by the divers. Once ‘box’ samples began to be recovered from the site, their excavation could begin. This involved careful analysis of the sediments and how they related to one another. Once the different layers within the samples had been excavated these were then wet-sieved; wet-sieving revealed the contents of the layers so that the volunteers could then sort out the different contents from each other for expert analysis of the environmental and anthropogenic settings of this site.

Further Analysis

In 2010, with support from the Leverhulme Trust via the University of York, English Heritage and the National Oceanography Centre (NOC) further processing, analysis and recording of artefacts recovered in 2009 took place. The finds were kept in the BOSCORF (British Ocean Sediment Core Research Facility) cold store at the NOC and the results of the processing integrated into the MAT dataset. Details of the analysis also contributed to the Bouldnor Cliff publication: Submerged Mesolithic landscapes of the Solent, published as a Council for British Archaeology Monograph in 2011.

The most significant finding that emerged from the analysis was the use of technologies on some of the worked wood that are 2,000 years ahead of anything else seen in the UK to date. The largest piece of timber recovered so far measured 0.94m long by 0.41m wide and provided a radiocarbon date of 6240-6000 cal BC (Beta 249735). It had been tangentially split from a large slow grown oak tree. This method employs wedges to cut a plank towards the edge of a tree so the grain runs almost parallel along its width. The technique can be used to create a flat plank. Once this is removed from a large oak bole, around three quarters of the tree’s circumference would be available for further conversion or fashioning. Another indicative factor was the relative angles of the medullary rays, which were almost parallel. This suggested the timber had been converted from the edge of a large tree in the order of 1.5m to 2m wide. The length of such a plank may well have been over 10m long.

This presents the possibility of creating a large, deep log boat or dugout canoe with the rest of the tree. If not the remains of a log boat, this tangentially split timber could have been part of a monumental building. Prehistoric timbers using these conversion techniques have been found elsewhere, although not until the Neolithic period over 2,000 years later. The timber was associated with many other pieces of trimmed and flattened wood. Some were surveyed and recovered while others remain beneath the old land surface. The true function of this exceptional site can only be resolved by further investigation which must be done before it is lost completely.

The work at Bouldnor Cliff continues to recover unprecedented material from the Mesolithic submerged forest, yet limited funds only enable us to pick at the surface. The submerged landscape has a one kilometre long exposed face that is continually eroding. Previous research has shown that between 0.1m to 0.5m of perfectly preserved landscape and covering sediments disappear along its length each year. This equates to between 100 and 500 square metres. With it goes the priceless archaeological record. The MAT has only been able to investigate a few square metres in detail but this alone has revealed a wealth of 8,000 year old immaculately preserved material that is second to none in the UK. The HWTMA continues to seek funding as it endeavours to rescue this unique and irreplaceable archaeology for the nation.

Archaeological investigation Bouldnor Cliff continued both under water and in the laboratory in 2011. In the summer two successful periods of fieldwork allowed the linking of all five submerged sites, covering a length of over half a kilometre, for the first time. As in previous years, further sampling work recovered fragile archaeological material that continued to be at severe risk from on-going erosion resulting from the powerful tides of the western Solent. In September, for the first time and despite inclement weather conditions, a live video feed was trialled onboard the dive-boat to allow crew to view what the archaeological divers were looking at and to communicate with them.

Laboratory work to investigate the delicate artefacts and organic remains recovered during archaeological work continued. This work was conducted at the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton. Samples, artefacts and organic remains were then put into cold storage to ensure their preservation and availability for future study.

Bouldnor Cliff is a virtually unique type of site within the archaeological record of the UK and disseminating the Trust’s research into the site remains important. 2011 saw the publication of the first monograph dedicated to the thirteen years of study undertaken by the MAT at Bouldnor Cliff. This contains information on all elements of the site, from innovative archaeological techniques, through dendrochronological and pollen analysis to specialist analysis of some of the earliest evidence for wood-working so far found in the UK.

The submerged landscapes in the western Solent were investigated in 2012 as part of the international Arch-Manche project. This is supported by the European Regional Development Fund within the Interreg IVa framework and includes the partners CReAAH from northern France, the University of Ghent, Belgium and Deltares from the Netherlands. The purpose of the research was to sample and characterise deposits from around the Western Solent that could help inform our understanding of sea level and coastal change. Sites that were inspected, recorded and sampled extended from Hurst Spit in the west, Bouldnor Cliff to the south and Tanners Hard, just outside Lymington Harbour.

A lull in the windy weather during June enabled peat samples to be recovered from the west side of Hurst spit. The samples were collected from a submerged stratified deposit and as such can provide dating and environmental material. The sample was collected from a deposit 7.6 metres below Ordnance Datum and it has become exposed because the protective shingle of the Spit has moved further east. This old land surface was protected by the creation of Hurst Spit and as such will help date its formation.

At Tanners Hard a submerged peat-capped cliff lying 4 metres below OD was surveyed in 2000. The cliff was in the order of 2 metres high with vertical sections exposed in places. A further basal peat deposit protruded from the foot of the cliff. Samples collected in 2000 dated the lower peat to 5290-4940 cal BC (2 sigma) and the upper peat to 4470-4240 cal BC (2 sigma). The site was revisited in June and July 2012 to record any changes to the submerged cliff. Erosion of the upper cliff surface was extensive demonstrating cliff retreat of up to 2 metres and reduction in the angle of repose from around 85 degrees to around 40 degrees. The 2000 survey area was extended a further 25 metres to the west for ongoing monitoring purposes.

At Bouldnor Cliff a series of erosion surveys were conducted along a 500-metre stretch of submerged cliff. Further evidence of human activity was discovered at both BCII and BCV. The finds provide tangible evidence of human occupation on a site that was to be lost to coastal change as the sea rose over 8 millennia ago. At BCV more worked Mesolithic timbers have become exposed.

Diary of a diver

During the 2012 season, the MAT were pleased to have two international maritime archaeologists joih them for a week: Nayden Prahov from Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridsky” in Bulgaria and Jeoren Vermeersch from Flanders Heritage Agency, Belgium. Read their summary of the week with the MAT below.

A Week of Underwater Field Survey with Hampshire and Wight Trust for Maritime Archaeology

As a young scholar with research interests in the field of underwater archaeology I have been impressed by the methodology and the results of the research projects in the Western Solent, Southern England, conducted by the Hampshire and Wight Trust for Maritime Archaeology (HWTMA), under the leadership of Garry Momber.

Led by the need and the demand for training of young Bulgarian underwater archaeologists, the director of the Bulgarian Center for Underwater Archaeology Mrs. Hristina Angelova asked Mr. Momber to accept a Bulgarian archaeologist as a volunteer and a student in his team. Mr Momber kindly agreed and extended an invitation giving me the chance to take part in a week of underwater archaeological field survey in June 2012. The Digital Institute for Archaeology at the University of Arkansas’ Center for Advanced Spatial Technologies (CAST) supported this undertaking covering my travel expenses.

In order to prepare for the project I was sent and reviewed publications about the results of the previous field work, as well as a detailed Archaeological Project Plan and a Diving Operations Plan.

The field survey included work at different sites – shipwreck, submerged Mesolithic site (Bouldnor Cliff II) and Submerged Ancient landscapes (Bouldnor Cliff) plus various underwater activities including field reconnaissance surveys, artifact recovery (flint debitage- cores and flakes), graphical documentation of submerged landscapes (seafloor, cliff, shipwrecks and a Mesolithic forest), taking of cores and samples (peat and sediment deposits, organic material), small scale excavations and other supportive activities. The atmospheric and sea conditions were challenging – rain, wind and waves, low water temperature, strong currents, low visibility.

Being new members of the team and diving for the first time at these sites and in such conditions, me and the young underwater archaeologist Mr. Jeroen Vermeersch from Onroerend Erfgoed – Flemish Heritage Institute, received special attention, instructions and detailed explanations of the tasks by the team and the project director Garry Momber. All our questions were carefully and thoroughly answered.

During the field project Jeroen and I took on a range of underwater tasks at different sites and we took maximum advantage of our training and participation. Despite being new to the site our work was appreciated and its results made a real contribution to the project.

The working days normally ended on land, in the harbour pub of Lymington town, where the results of the days were discussed, the documentation and the collected materials revised, and report working sheets were filled. At the end of the project all the field drawings of the site BCII were collated in a single plan, which was a rewarding result.

Probably the most valuable part of my participation was the communication with the team. It consisted of scholars from HWTMA and volunteers – divers with remarkable experience. They were all well organized, working in perfect coordination, conducting multiple tasks despite the hard sea conditions, being always friendly, helpful and supportive to each other. Mr Momber was organizing the work, always serious and at the same time smiling, with his sense of humour creating positive mood and attitude.

At the end of this exciting and moving week I wished to meet, work and dive with the team again. Maybe one day on a Bulgarian underwater site. A good goal to work for.

Nayden Prahov

Sofia University “St. Kliment Ohridsky”, Bulgaria

A week at Bouldnor Cliff

In the week of the 11th of June I was privileged to join the HWTMA on their underwater research in the Solent. There were many reasons why I wanted to dive with them on archaeological sites. Not only do I need to get a certain amount of dives in, in order to keep my HSE dive qualification up to date to be able to dive in Dutch and Belgian waters, also it is very interesting to share experiences among researchers. Since the HWTMA has quite some experience in this area and in the past worked with the Flemish Heritage Agency, it was a logical decision to ask Mr Momber if I could join him and his team during one week in June.

The Solent is rich of sites such as shipwrecks and sites dating to the Mesolithic. The latter ones are quite unique and show very good preservation in situ. On the other hand due to the constant erosion processes these sites are under clear threat and need to be looked at and monitored on regular basis.

The extra work experience was very important for me since our agency in Flanders only has a few people who do archaeological research in the North Sea area. Gaining extra knowledge and experience therefore is essential in order to keep the learning curve going up. In this way the HWTMA was an ideal institution to work with, since they already gained so much experience in the field.

Together with another volunteer, Mr Nayden Prahov who is an underwater archaeologist from Bulgaria, we were instructed to execute certain tasks on both shipwrecks and on prehistoric sites. The different diving conditions (such as the strong current in the Solent) were sometimes a challenge to us. Thanks to the good guidance of the team we were able to execute the tasks during the course of the week and thereby contributed to the work of the Trust.

Apart from the dive experience it was a good thing that afterwards there was enough time to socialize as well. The debriefing occurred in the local pub of the harbour and in the evening there was time to chitchat and to drink some Belgian beer or be treated with a terrific good Bulgarian meal.

The contacts that were laid with the archaeologists from the UK and Bulgaria and the enthusiastic volunteers certainly helped to make the week a huge success and the training and experience gained will hopefully be put into practice in Belgian waters too.

Jeroen Vermeersch

Maritime Archaeologist

This site continues to provide an opportunity to study an archaeologically rich prehistoric palaeo-landscape, cost effectively and in detail. Its investigation can address key research questions and help inform decision makers when addressing the impact on comparable sites ahead of offshore development impacts. During 2013 the site was subject to extensive research as part of the Arche-Manche cross border project.

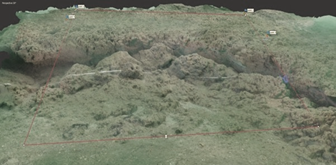

Geophysical investigation

Analysis of geophysical survey data that has been collected from the seas around Europe over the past few decades has revealed a network of well-preserved pre-inundation landscapes with relict river channels, lakes and sheltered lowlands.The western Solent is an example of a pre-inundation landscape that has become accessible.

It was a resource rich valley cut by a river floodplain that proved to be suitable for occupation. Like other fluvial systems that drained the UK at the end of the last glaciation, it filled with estuarine silt as sea level rose.Today, the process of sedimentation has reversed following the formation of the Solent. This now runs perpendicular to the original channel.

As a consequence, erosion has cut a natural section through a 7m thick accumulation of brackish water silt to expose a submerged forest 11m below UK Ordnance Datum that dates to over 8,000 years old. Once exposed, erosion can be up to half a metre a year. The loss of material is unfortunate but it has provided access to the base of a palaeo-channel that would otherwise be covered by many metres of sediment.

Researching exposed zones

Today, underwater at Bouldnor Cliff, a 1km long corridor of extremely well preserved landscape is exposed. Within it, four archaeological sites have been identified and two are being investigated in detail. One site is associated with a fluvial sand bar and is dominated by worked and burnt flint, while the other is a site of industrial activity with well-preserved worked timbers suggesting the construction of a log boat. The different sites are recorded in relation to their surrounding landscape features to characterise the most attractive areas for occupation. These will be the locations with the highest archaeological potential. Characterising analogous sites prior to commercial development can help inform mitigation strategies and reduce risks of impact.

Excavation and analysis

Over the last 10 years, a range of methods have been employed to excavate and record material from the palaeo-deposit. Box sampling was used for recovery of fine environmental and archaeological material while larger pieces of worked timber were raised individually. To date over a thousand pieces of worked and burnt flint have been recovered from just 9 square metres while over 600 have been recovered in the last 2 years following the natural erosion of a 8 metre wide section. Dozens of timbers, pieces of string and extensive samples of charcoal have also been recovered.

The period of occupation is late Mesolithic but the discovery of tangentially split timber and a carefully prepared bi-facial flint axe demonstrate technologies not apparent until the British Neolithic. In addition, the use of obliquely blunted blades, akin to tool types found in the ParisBasin, infer cultural links with the continent. The site brings into focus patterns of Mesolithic occupation, it queries our understanding of regional technological capabilities and raises questions about human dispersal during the final severance of Britain from mainland Europe. While inferences can be drawn from the archaeological record in adjacent lands, the archaeological material that is being discovered underwater contains unique evidence from this time of great change.

2014-2016

Over the past 10 years, monitoring the Mesolithic deposits at Bouldnor Cliff has demonstrated lateral erosion of up to 4 meters in the most affected parts of the archaeological sites. Therefore it has been an essential part of the fieldwork to rescue archaeological material that is at risk of immediate loss. In 2016 the Trust retrieved another 24 pieces of worked timber, adding to the collection of remarkable artefacts recovered from the site. One of these timbers proved to be of great significance as it showed evidence of being tangentially split. This is a practice that has previously only been recorded during the Neolithic.

The research on Bouldnor Cliff conducted by the Trust has demonstrated the significance and research potential of the site. This area was occupied by humans only a few hundred years prior to the land separation between Britain and the European mainland. This historically significant period is still poorly understood, as archaeological remains from this era do not tend to survive very well on dry land. To this day, Bouldnor Cliff remains the only submerged Mesolithic settlement in Britain. This is significant as the archaeological remains found at the site have been remarkably well-presevered in the anaeorobic conditions on the seabed.

In furtherance of our fieldwork at the site, the Trust also conducted a photogrammetry survey. This has allowed us to create an interactive 3D model of a section of the Bouldnor Cliff site. This model along with other 3D-models of artefacts and wood from Bouldnor Cliff, are freely accesible here.

In 2016 we teamed up with DigVentures to create more awareness for Bouldnor Cliff. The articles from the collaboration can be found on their website.

2017

In 2017 two fieldwork sessions were conducted at Bouldnor Cliff. The MAT team were joined by researchers from the For Sea Discovery programme, who helped with recovering more wood and sediment samples for analysis. This year the first tranche adze from the site.

A BBC reporter joined the team on the dive boat while they conducting fieldwork. This feature aired on BBC Radio 3.

During the summer of 2018, a series of dives began a process of photogrammetric survey across sites Bouldnor Cliff II and V (BC-II & BC-V). Over 9,000 still images were collected, which are revealing fine details of the landscape and enabling us to create 3D digital models of the sites for visualisation and monitoring. During the survey, exposed material was recorded and rescued. In total, 152 burnt and worked flints were recovered after they had eroded from the foot of the cliff at BC-II, while 14 newly exposed pieces of worked timber were saved. This included two upright posts, one of which was a composite structure made of three pieces. A further post was recorded protruding through the peat indicating the remains of worked wood just below the surface. This is very promising as it will invariably be associated with material that could help reconstruct the settlement. The archaeological horizon lies just below the surface of the seabed, so, while this means it is threatened by loss as the thin layer of peat over it is steadily taken by the tides, the limited cover that remains makes it relatively easy to excavate. This provides a window of opportunity to record this irreplaceable and unique site before it is lost.

2019

The 2019 fieldwork season has made an exciting new discovery at Bouldnor Cliff: a new feature, constructed of over 60 pieces of split and trimmed timbers, some of which are up to a metre long. Many were converted from the edge of a large tree. The timbers were laid in a position covering an area approximately 1m by 2m, although evidence of other structures can be seen in the adjacent seabed. Three layers of flattened worked pieces were placed on top of horizontal round-wood that ran underneath and perpendicular to the main structure. The feature appears to be a platform. It would have formed a solid surface or hard standing in its wetland setting, being close to a stream that ran down from the Isle of Wight.

Inspection in May 2019 revealed that this feature had only recently become exposed as it was not seen in 2018. The ongoing erosion meant we had to record and recover it or lose this unique piece of our past forever. A photomosaic, pre-disturbance survey, of the site was taken at the outset before the different elements of the structure were tagged. Further images were collected as the timbers were removed and white string was used to help define the blackened wood against the blacker peat. This has helped with the reconstruction following recovery. The lower layer of the structure can be seen in the image below. This challenging work was achieved by the MAT team with the help of many Friends of the Trust.

You can help us raise funds to carry out further work here.

2020

Our team of marine archaeologists from the Maritime Archaeology Trust returned to Bouldnor Cliff (BC) to inspect and record the site on a couple of cold, but clear mornings in November. We first inspected ‘BC-V’, which is the World’s oldest boat building site. Here we recorded more exposed timbers. These were found at both the east and west ends of the site. This was where we found ‘Britain’s most intact Mesolithic platform’ which was rescued in 2019. The conditions were dark but we recorded the areas that were eroding to monitor any change and prepare for rescue in the coming season (Figure 1).

On the second day, the team visited the area where many flint tools are eroding from the seabed at ‘BC-II’. This is the area that we found the oldest evidence of wheat in the UK. The evidence is eroding from beneath a collapsing clay cliff (Figure 2).

BC-II is under particular threat because the artefacts all lie within, and on an ancient sandbar. This was covered by mudflats as sea level rose but recent erosion has eaten into the side of the old deposit allowing the sand to seep out onto the floor of the Solent. The moving sand carries artefacts, which can then be washed off site by the strong tides (Figure 3).

Each time we visit the site we find freshly exposed tools (Figure 4). This expedition was no exception as we found 38 new worked flints that had eroded from an area that was inspected a few months earlier. Significantly this included including a complete Tranchet axe (Figure 5). This is only the second axe to be found. (Figure 6).

The Maritime Archaeology Trust team have serviced the equipment and booked boat dates to dive throughout the summer, beginning in May. The plan is to continue the recording and monitoring of the site. Once recorded, we will recover any items under threat of loss. These will be researched, conserved and put on display at our Museum on the Isle of Wight. The interpretation will contribute to online education resources.

The location with the richest source of archaeological material will be cleaned and a sample will be taken for sedaDNA analysis. This will provide the DNA sequence of the plants and animals that were at the location 8,000 years ago.