A dramatic introduction to intended trans-oceanic sailing followed by its untimely demise, the sailing vessel Irex could hardly have had more misfortune on its maiden voyage! Volunteer Roger Burns recounts the events of its short and expensive life.

The Irex features within the Unpath’d Waters Needles Voyager and is also being researched as part of an investigation of Metal Hulled Sailing Vessels in English Waters , so this ship features within multiple MAT projects.

The Irex

Launched on 10 October 1889 by John Reid & Co. in their Newark Yard, Port Glasgow and completed the following month, the Irex was a steel hulled, three-masted sailing vessel, 92.11m long, with 13.14m beam and 7.41m deep. It had four boats, two of which were lifeboats. Owners included Mr William Wallace, and Mr Alexander Mackay, the managing owner being John Daniel Clink of Greenock. The Irex was registered at Greenock on 5 November 1889, ON93224, with tonnage 2,348/2,249 grt/nrt. As we shall see, it leaked slightly on its maiden and only voyage, so it is worth a brief look at the expertise of the shipyard. They were prolific builders; from a paddler in 1845 and an 1846 floating church permanently moored with pulpit and 400 pews, the first sailing vessel (SV) was launched in 1852 with many more mostly three-masted, plus barges and naval vessels, steamers from the late 1870’s, all of these in rivetted iron, some composite yachts, and from 1878, changing to steel steamers and sailing vessels. The Irex was the penultimate ship built before the yard was taken over in 1909 by well-known shipyard Barclay, Curle and Co Ltd., and then in 1912, Swan, Hunter and Wigham Richardson acquired a controlling interest in Barclay, Curle and Co Ltd.

The Voyage and Wreck

Having calibrated its three compasses in Gare Loch and loaded with cargo comprising some 3,600 tons of iron sewage pipes, pig iron, metal kitchen pots and earthenware pipes, it set sail from Queen’s Dock in Glasgow with 36 crew under Captain Hutton bound for Rio de Janeiro. Towed by a tug to the Mull of Galloway where it cast off, the Irex’s troubles started, summarised in the narrative augmented by location maps, Figures 1A & 1B, and a Daily Timeline, Figure 2.

Figure 1A : Voyage landmarks until 1 January 1890, 1B : Voyage landmarks 1 January 1890 to wreck 25 January 1890

Figure 2 – Daily Timeline 10 December 1890 to wreck

With the tug having cast off, sail was made but a strong breeze from the SW hindered progress and by 13 December, a gale developed, sail was reduced but the Irex rolled heavily, its cargo shifting, so it put into Lamlash, Isle of Arran, for shelter. Examined by Mr Clink and a surveyor, it put back to the James Watt Dock in Greenock, some 20 miles downstream of the Queen’s Dock. There, some of the crew deserted and joined other ships. The cargo was carefully restowed by stevedores which took 1,000 hours; this confirmed that the original stowing was good, and the wooden dunnage appeared to have moved. The Irex was towed to sea on 24 December, this time with 35 crew, two stowaways, and Captain Hutton. The crew included six apprentices, one of whom had been to sea previously. The next day, another gale developed, so refuge was taken in Belfast Lough, whence it departed on 1 January 1890. Weather was initially favourable, but strong head winds developed and water was shipped, disabling two crew, one with a broken arm, the other with a broken leg.

The Bay of Biscay was reached on 22 January, sails were lost, a leak through rivets developed with 15 ins (c. 0.4m) water in the hold, pumping was started, the wind increased again to what was described as hurricane force, the ship laboured and lurched, the cargo again shifted with pipes rolling about striking the hull, and on 23 January, the crew asked Captain Hutton to put back. Initially he refused as doing so would reflect badly but later in the day having established from a passing steamer it was just over 200 miles to Falmouth, he ordered the ship around, the intention being to put into Falmouth. The weather eased allowing rope coils to be taken below to prevent the hull being struck by pipes. Sighting the Lizard Light on 24 January, a pilot request was made as the risk of entering Falmouth without was unacceptable, but none materialised, so having gone too far east, sail was set for Plymouth at 04.00 on 25 January. A thick fog developed, clearing by the evening when at 19.00 they sighted St. Catherine’s Light some 15 to 20 miles distant, a strong W. to N.W gale blowing. The Irex was under reefed foresail, reefed main upper topsails, three lower topsails, and foretopmast staysail, making about ten knots on a N. by E. course.

At about 22.00, a bright light was seen ahead, which the Captain took to be a pilot boat, so a course was set for it, the captain burning a blue light to contact it. Shortly afterwards, the Irex struck the rocks in Scratchell’s Bay, bouncing off once, then became stuck, south of Needles Point and within 200 m of the beach. The sea was breaking over the vessel, and the Captain ordered the boats to be got ready. The Captain, mate, and some of the hands were engaged clearing away the lifeboat on the starboard side of the bridge aft, when a heavy sea was shipped which carried away the two boats on that side and all those employed in clearing them away, and they were not seen afterwards. The Second Officer then ordered the crew to take to the mizzen rigging.

The Rescue

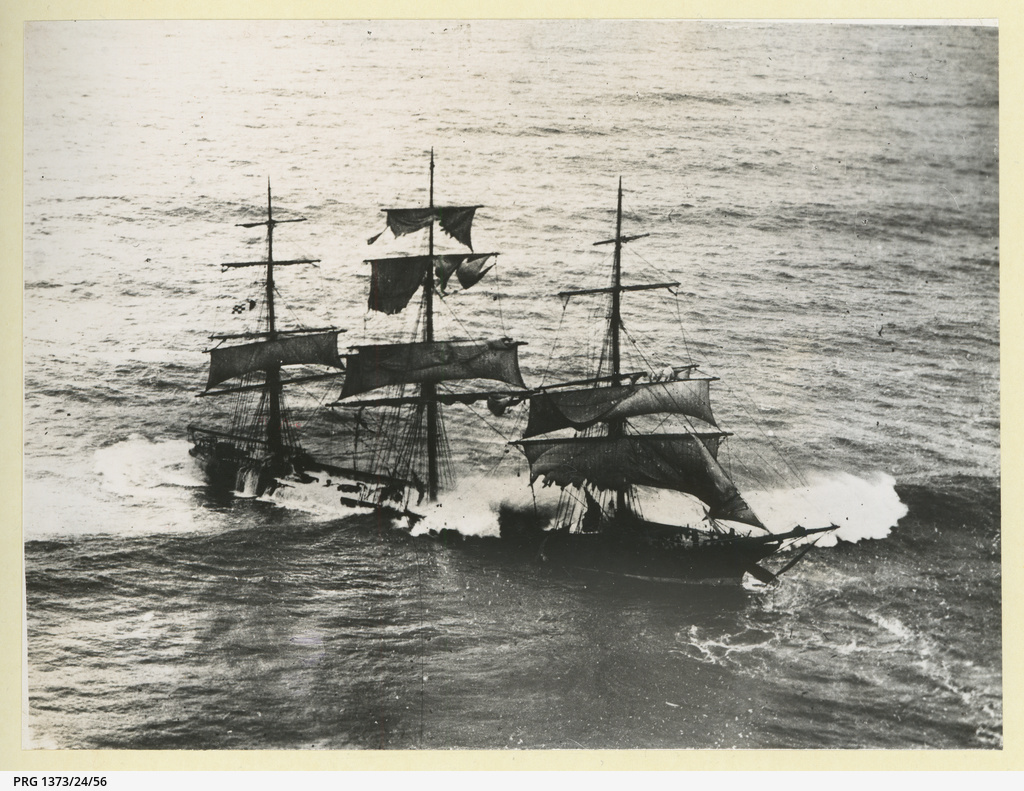

It was daylight the next day, when at 09.00 the Irex was spotted from the Needles Battery, informing the Totland lifeboat. A steam collier, the Hampshire, also saw the Irex but neither were able to approach the Irex due to the storm. Figure 3 shows the deck swamped by the waves.

Figure 3: The Irex after going on the rocks, undated.

Source: State Library, South Australia, no known copyright restrictions, part of the A.D. Edwards Collection.

It was noon the next day before a tug arrived with a lifeboat but the heavy surf prevented any rescue. Rocket apparatus from Freshwater arrived, and from the 400ft (c. 122m) high clifftop, fired, at the first attempt, a line right over the ship, and eventually a breeches buoy was rigged. From 16.00 the crew were taken ashore through the efforts of the soldiers, coastguards and local residents. During this rescue, one man fell to the deck of the ship, regained the line, fell again and was washed overboard, drowning. In total, seven lost their lives. The state of the deck afterwards is illustrated in Figure 4A, and one of the apprentices who went on to become a master mariner is seen in Figure 4B.

Figure 4A – The subsequent state of the deck.

Figure 4B: Apprentice Exton Swaffield.

Source of both images: Kindly permission of Carisbrooke Castle Museum, references P.1986.46 & 2000.23A respectively.

On 31 January, Queen Victoria met the second mate and seven of the crew at Osbourne House. The following day, all those from the coastguards and the soldiers who had assisted in the rescue were received by the Queen.

0n 24 April, salved stores comprising barrels of mess beef and pork, tinned provisions, white lead, rosin, paints, oils, varnish, various containers of linseed oil, about 900 cast iron cooking pots and glazed drainpipes were auctioned at Cowes. The wreck was auctioned, as seen, on 29 September 1890, and more salved materials comprising nearly 100 sails, deck gear, and a new steam winch complete with transport carriage were auctioned at Cowes. About 2,500 tons of cargo were sold at auction at Southampton on 3 June.

Initially, the wreck remained upright and was included in paddle steamer sightseeing excursions but in early November 1890, a gale broke the ship in two near the mizzen mast.

The Inquiry

At the behest of the Board of Trade, an Inquiry into the loss of the Irex opened at Greenock Sheriff Court on 20 February 1890, with a further four sittings (fully transcribed here within the Irex’s document list).

Evidence was heard from several of the crew, the owners, and the Partner of the firm of stevedores at Greenock. Evidence from some crew was discredited, and although Captain Hutton was not considered favourably by some crew, several witnesses spoke highly of him. It emerged that Captain Hutton had not slept for several days caring for his ship, and it was found that he had misinterpreted the bright light to which he had steered anticipating it to be a pilot boat but which was in fact the Needles Lighthouse. The steward testified that Captain Hutton had about 200 charts on board and had two charts of the English Channel open. The court found that:

- The cargo was properly stowed on both occasions and had shifted due to the severity of the storms;

- The ship was sufficiently manned;

- Verification of the position of the ship when St. Catherine’s Light was seen could not be answered as the two key witnesses, the Captain and First Mate had both drowned;

- Cause of grounding was the master steering for the Needles Light believing it to be a pilot boat, and continuing until it was too late to correct the mistake; and

- No blame was attached to the owners.

On a final note, the Irex cost the owners £25,000 in 1890 (c. £2.65million in 2024) which was insured but losses from the charter amounted to some £5k to £6k (c. £532k to £638k in 2024).