MAT volunteer Roger Burns explores the voyage and collision history, and First World War loss of the cargo steamer SS Kurland. One incident in 1891 was replicated in 2021, albeit with considerably more world-wide repercussions.

The Kurland was originally named William Branfoot when launched as vessel no 241 from the North Sands yard by J.L. Thompson & Sons of Sunderland. It was a steel hulled, single deck, schooner rigged, cargo steamer on 10 September 1888 built for local owner William Branfoot, changing in 1894 to the Tyzack and Branfoot Steam Shipping Co. Ltd., 18 John Street, Sunderland. Of construction typical for the period, it was first registered ON95275 at Sunderland, 86.6m long with 1.6m beam, 2,022/1,235 grt/nrt and powered by a 3-cylinder steam engine having two boilers, driven by an iron propeller. The ship was fitted with four steam winches, a steam windlass, and steam steering gear. Water ballast tanks extended the full length of the vessel, and six steel watertight bulkheads were included.

Cargoes were typically transported between North European ports, such as London, Antwerp, Spain and Tyne ports. Also, to North and South America ports, including New York, Buenos Ayres and Delaware*. These voyages were punctuated with sailings to India, Ceylon, Malaysia, Singapore, Hong Kong, and Japan.

In 1897, the William Branfoot was sold to Argo Dampfschifffahrts Gesellschaft, a German company from Bremen when it was renamed Kurland and re-registered in Antwerp, and sold again to a Belgian company named Compagnie ens Ocean in 1908. The North Atlantic voyage pattern continued although information is sparser as there was a contemporaneous similarly named vessel and respective voyage identities are less certain.

Cargoes carried are not generally recorded but cotton or coal was carried on occasion. Incidents during this pre-war period included, as William Branfoot, a collision in November 1890 in the Thames with SS Zeta forcing the William Branfoot back to port for repairs, and a grounding on the bank of the Suez Canal in October 1891, obstructing navigation for two days (unlike the well-known six-day obstruction in 2021) ; later, as the Kurland, departing Antwerp with coal for New Orleans, colliding with two coal laden lighters, the Ida and the Prince Baudouin in the Scheldt in January 1904.

Voyaging, unarmed, from New York to Calais, carrying a cargo, described below, which led to it being known as the “Rifle” wreck, the Kurland successfully evaded an attack by a German submarine on 13 December 1917. Later that morning, at about 05.00 when 4.8 nautical miles ESE of Dunnose, the Kurland collided with the significantly smaller SS Deventia and sank, having been struck amidships, causing it to sink in minutes. The fate of the 25 crew is not recorded. The British steamer Deventia, went astern and steamed away, either in ignorance or choosing to ignore what had happened, and continued to operate until wrecked off the Devon coast in 1929.

It was not until some 50 years later that Martin Woodward, founder of the Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum at Arreton Barns, Isle of Wight, discovered the builder’s plate by the keel of the wreck and proved the identity of the vessel as the Kurland. For many years, the identity had been mistaken for the SS Leon, a similar wreck, and there is another unidentified wreck close to the Kurland. Having carried a cargo of boxed rifles and ammunition, bricks, horseshoes, wheels, tyres and other supplies for the Belgian Government, the reference “Rifle” wreck was coined, and discovery of 1880’s Belgian Mauser rifles cemented this identification. Springfield rifles and .303 Lee Enfield rifles were also found. It was additionally carrying shoes for mules and horses at the Front, a vital commodity with background here.

The MAT dived the Kurland in 2016 and 2017, and on both occasions, visibility was poor at only a few metres. The wreck is approximately 30m deep, and lay on a sand and shell seabed within an area of scour, particularly around the bow and port side. Standing upright but broken up in places, one of the holds still held the reported cargo, and amidships, parts of the hull with structural frames still stood. The boilers were the most prominent items standing some 4.5m high. Over the last century, the wreck has significantly degraded, with deformed structural elements, presenting confusing areas of wreckage.

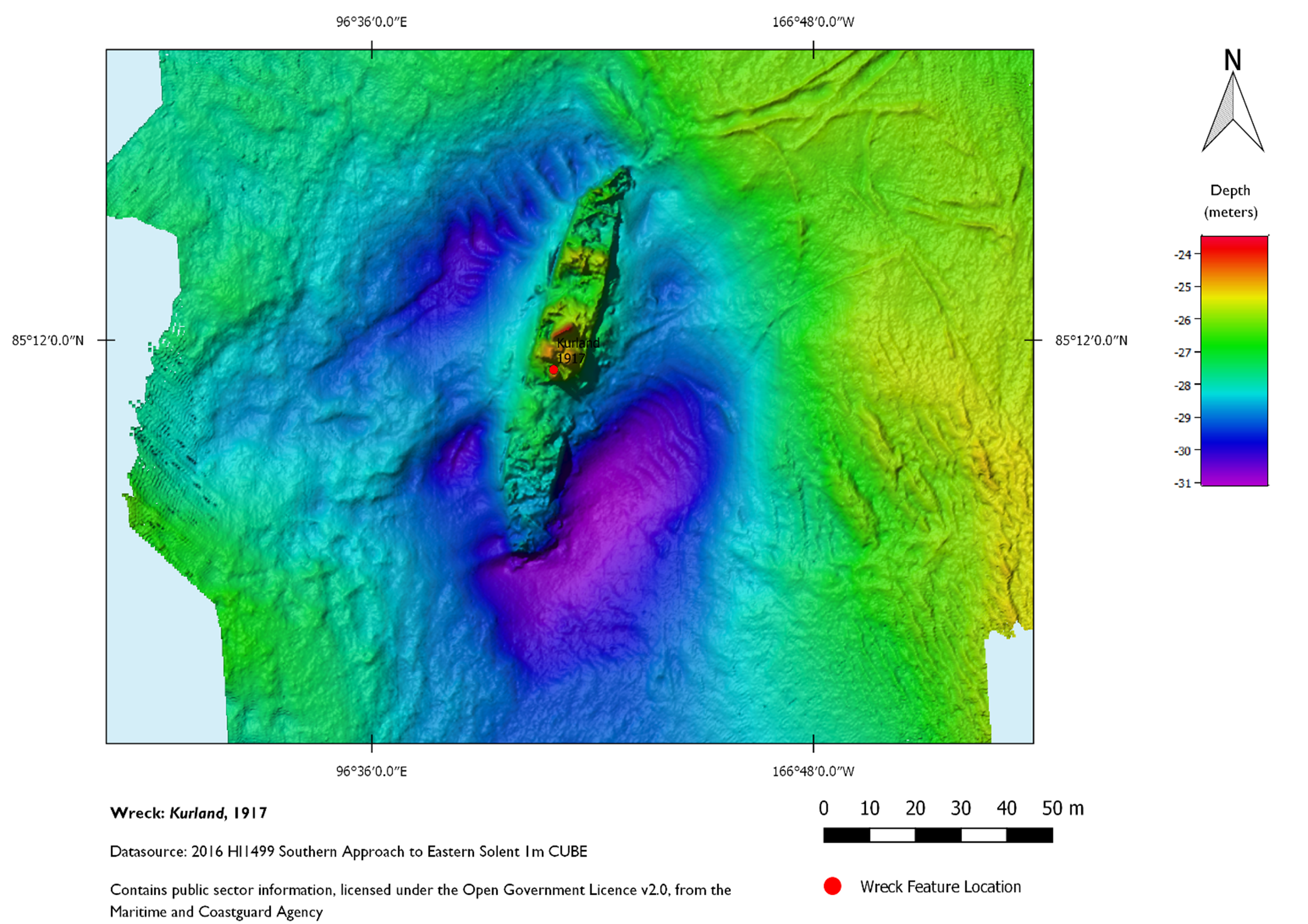

Figure 1: Bathymetry Image of the Kurland Wreck. (Contains Public Sector information licenced under the Open Government Licence v.3 from the Maritime and Coastguard Agency)

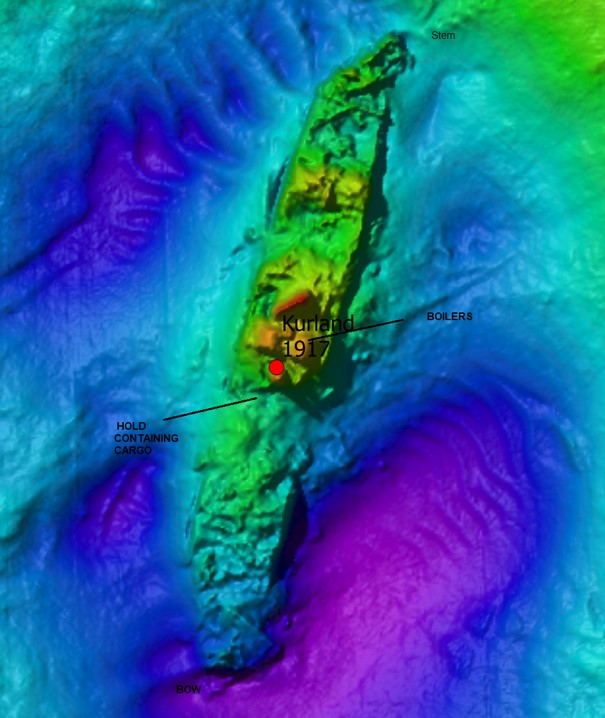

The bathymetry image of the wreck shows it is upright, the bow facing SSW with some displacement of the bow and stern towards the east, a confused picture along the vessel, and scour at the bow and the forward areas of the port side, with less scour diagonally opposite. Figure 2 is an enlargement of the wreck, showing the boilers and hold containing cargo.

Figure 2: Close up of the geophysical image

Figure 3 of the wreckage shows piles of the cargo of canisters or possibly shells, and Figure 4 shows piles of horse and mule shoes lying amongst the cargo. Both images are by MAT.

Figure 3: Canisters or shells

Figure 4: Piles of horse or mule shoes

Figure 5: Builder’s Nameplate recovered by Martin Woodward

Whilst the ship in itself was a common type, the Kurland’s fascinating cargo is what truly sets the site apart from other shipwrecks of this age. Additionally, the site has international significance, particularly for Belgium, and historical relevance due to its direct links supporting the First World War. Due to this significance, the Kurland was studied as part of the Trust’s Forgotten Wrecks map and further information on the Kurland’s artefacts can be found in the site report.