For our Metal-Hulled Sailing Vessels project, generously funded by generously funded by Historic England and Lloyd’s Register Foundation, volunteers are investigating the potential and significance of the collection of metal-hulled sailing vessels located within English territorial waters. One of these vessels is the Preussen, a unique ship that at one point, was the largest sailing ship in the world. MAT volunteer Jane Thakker explores the wreck in greater detail.

Figure 1: The Preussen in full sail, source: Allan C. Green, Wikimedia Commons

The Preussen was the only five masted, full rigged, cargo ship ever to be built, with a spread of canvas twice as great as the largest British sailing ship. Due to its unique appearance and excellent sailing characteristics sailors called it the “Queen of the Queens of the Sea”

The Preussen was built at the Joh. C Tecklenborg shipyard in Geestemunde in 1902, for the F Laeisz shipping company and named after the German state and kingdom of Prussia, launched on 7th May 1902. It was designed to round Cape Horn and return at speed, making up to 20.5 knots and was built to weather every storm, and even tack in force 9 winds, although in such conditions eight men were needed to hold the 2m double wheel.

The Preussen had a waterline length of 124m, an overall length of 132m and had a displacement of 11,330 tons, with a total sail area or 6,806 square metres. Not only was the hull made of steel, but the masts and spars were constructed of steel tubing and most of the rigging was steel cable. The only wooden spar was the gaff of the small spanker. It was manned by a crew of 45, supported by two steam engines which powered the pumps, the rudder systems, the loading gear and the winches but used sails for propulsion. It was designed as a so-called “three-island ship”, a ship with a third “high level deck” amidships beside the forecastle and poop deck. The midship island or the midship bridge, is also called a “Liverpool house”, because the first ships equipped with that feature came from Liverpool yards. Dry and well-ventilated accommodations for crew, mates, and captain, as well as the pantry and chart room, were built in this middle deck.

During it’s service, the ship was used in the saltpetre trade with Chile, setting speed records in the process, sailing an unequalled record voyage from Lizard Point to Iquique in 57 days. The Preussen also made twelve round trips from Hamburg to Chile, and one journey around the world via New York and Yokohama under charter to the Standard Oil Company. For eight years, it carried both nitrates and general cargo.

Figure 2: The Preussen in New York, 1908, source: Bain News Service, Wikimedia Commons

On the morning of the 6th November 1910, the Preussen, under the command of Captain Jochim Hans Hinrich Nissen, was on an outbound voyage to Chile, carrying a cargo that included pianos, cement, railway tracks, wax, wool, sugar and bricks. The ship was rammed by the Brighton, a mail packet operated by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway Company, eight nautical miles south of Newhaven. Contrary to the “rules of the road” the Brighton had tried to cross the bows of the Preussen, having underestimated its speed. The Preussen was seriously damaged and lost much of its forward rigging making it impossible to steer the ship. The Brighton returned to Newhaven to summon assistance and the tug Alert was sent to aid the stricken ship. A November gale meant the Preussen could not be towed to the safety of Dover Harbour, but instead was anchored off Dungeness. However, both anchor chains broke and despite three tugs taking hold of the Preussen in an attempt to to tow it to Dover, the ship again broke loose and was driven onto rocks at Crab Bay. With a south-south-west gale and breaking heavy seas, tugs were sent from Dover to assist, but due to the violence of the gale and the dangerous position of the vessel they were unable to come close enough to help.

When maroons were fired to summon the lifeboat and the rocket apparatus crews, the lifeboat was launched with difficulty and taken in tow by one of the Dover tugs. The St Margaret’s rocket crew found it impossible to get a line over the wreck from their position high on the cliffs, so one of the men undertook the hazardous task of climbing down the cliff face on a rope ladder to enable the apparatus to be moved down. However, the East Cliff Coastguards made their way along the foot of the cliffs and succeeded in getting a line over the Preussen’s main rigging, working in the surf with the sea up to their waists.

On the return of the lifeboat, members of the crew stated that they encountered a terrific sea, which lifted and tossed their craft about like a cork. The men had great difficulty in keeping their seats. When they got near the Preussen, the lifeboat crew shouted, but could get no response, although lights were burning in the deckhouses and other parts of the vessel. The lifeboat had one or two

narrow escapes, nearly being capsized, and their position became so dangerous that the tug which had been in charge of her towed her off, and with great difficulty she returned to Dover.

No fewer than twelve tugs were on the scene in an attempt to tow the ship from its perilous position, but they had to abandon their efforts due to the weather and seas. The crew remained on board gathered on the midship deck house wearing cork jackets, and at times they waved their hats at the crowds of spectators onshore. Captain Nissen told reporters that his crew had said “Captain, we will stick by you. At the worst we can swim ashore and we have lifebelts.” One of the crew, described their experiences after the collision with the Brighton:

“As the Preussen was making water badly we put back to Dungeness. We were pumping the whole night and the next morning to keep the water down. First our starboard anchor was lost in the terrific gale, and then our port anchor went and we were driven out of Dungeness anchorage. Tugs tried to tow us into Dover, but nothing would hold, and we were driven ashore under the Foreland cliffs, the ship striking violently. We have had a terrible time in the gale since she struck, and have been wet to the skin the whole time. Captain Nissen is a splendid commander, and we all decided to stick to the ship as long as there was any chance of getting her afloat. The men who were working forward had a very narrow escape when the foremast fell. The steel mast, with the mass of rigging attached, came down practically without warning, and how any who were working in that part of the ship escaped is little short of a miracle”

On the Tuesday morning the two passengers from the Preussen, a painter of seascapes and a navigating instructor, were landed and, later in the day, eighteen of the crew, consisting of the youngest hands, were brought ashore in a lighter and taken to the Sailors’ Home. The Dover Express reported that before the eighteen men came ashore Captain Nissen mustered the whole ships’ company and read them the following telegram from the Kaiser:

“I desire to express to the owner my warmest sympathy. I should like a direct report regarding the result of the catastrophe, and especially about the fate of the brave crew, which causes much anxiety.”

The remaining crew attempted to get pumping gear from the German vessel, Albatros, on board, and during the night the Albatros came alongside to try and lower the water in the ship, with no success however, as the water flowed in with the tide indicating how badly the hull was damaged. After efforts to re-float the Preussen had failed a contract was made with a Mr Callen of Dover to salvage all the gear and cargo that he could from the wreck.

“The cargo amounts to some 10,000 or 12,000 tons, and the 100 pianos and other important items will first be taken off. It had been expected that the remaining 30 men of the crew would be landed on Tuesday night, but as the weather had moderated they decided to remain on board and assist in the salvage operations. It is stated that a fleet of lighters will be sent to Dover from Hamburg to receive the cargo.”

Pending the arrival of lighters to take off the cargo, the sails, steel rigging and movable deck fittings were removed from the wreck and transferred to the German salvage steamer Albatros. While fine weather lasted the wreck was stripped of everything that could possibly be removed. The vessel, since she struck, had dragged completely over the Fan Point reef of rocks. In recognition of the pluck shown by the Dover lifeboatmen in endeavouring to rescue the crew a visitor to Dover sent the Hon Secretary of the lifeboat £5 for the crew. The most valuable salvage was the bags of wax and wool. Sums varying from £100 to £170 were paid to different parties of boatmen, who were working in small syndicates on the wreck.

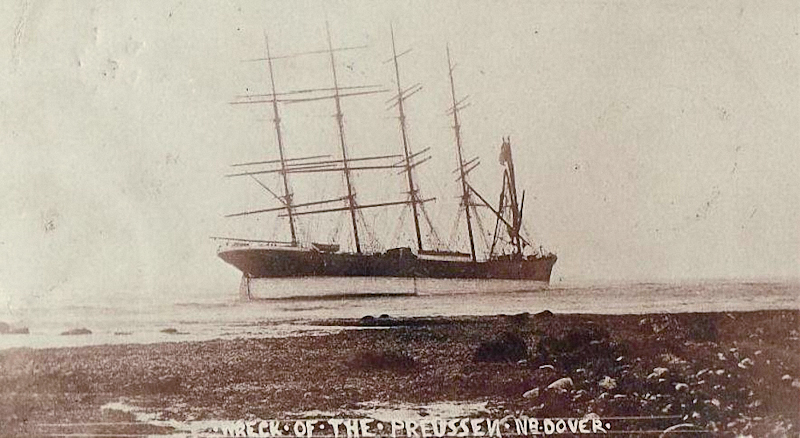

Figure 3: The Preussen stranded on the coast, November 1910, source: Botaurus, Wikimedia Commons

Court proceedings were held in London, the verdict being announced on 12th April 1911 and reported in the English journal Syren and Shipping. The verdict of the court was that the Brighton was deemed solely responsible for the loss of the Preussen. The master of the Brighton was found to be at fault and lost his licence as a result. Newspaper reports had appeared in all the local papers, the Tuesday Express, Dover Express, Westerham Herald, Dover Chronicle and the Herne Bay Press, and the ship featured in cinematographic films.

A collection of research papers published by Southampton University, “Sea Lines of Communication: Construction” includes a chapter entitled I Was At The Helm When The Preussen Ran Aground and is a translation of the memoirs of Christian Friedrich Warming who served as an able seaman on the Preussen, and is introduced by his great-grandson, Rolf Warming. There are very detailed descriptions of the ship itself, and of the catastrophe, and C. F .Warming concludes by saying that, in later years, as master of his own ship, whenever he passed Dover he kept close inshore so that he could see the wreck of the Preussen lying under the chalk cliffs, exactly where it had struck. Over the years, however, Warming says that the ship gradually began to disappear beneath the waves, although even up to the beginning of the Second World War a few frames were still visible to above the water – the remains of one of the largest and most beautiful sailing ships ever made. You can read more about this account of the Pressuen running aground here.

The wreck of the Preussen lies broadside to the great chalk cliff of Fan Point and old bottles and gas lamps have been found in heavy kelp, and “stone” cement barrels run the length of the forehold. The ship is now completely broken up, with the majority of the wreckage lying in a scour. Two masts are visible about 10m apart and there is a large amount of steel plate, but only the ribs of the hull now show at low water springs