A query from a local Bude resident for more information about the shipwreck that her mum had been named after – the Miura – began another adventure in the archives and on the beach for MAT’s Head of Research, Julie Satchell. Armed with a historic photo of the ship on the rocks and an account that “at high tide in October the sea goes in and out of the boiler under Sharpnose Cliff and it goes off like a rocket”, an initial beach visit managed to identify approximately where the wreck would be, but it was clear that a particularly low spring tide would be needed to see any potential remains.

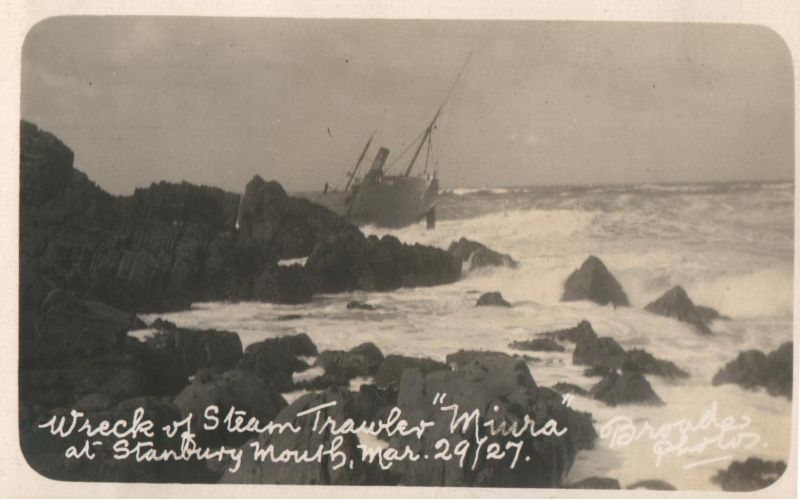

The wreck of the Miura, copyright unknown.

The Miura

Research revealed that the Miura was built in 1916 in Middlesbrough by Smiths Dock Co Ltd at South Bank. The owners were Neale & West Ltd and the intended use was as a fishing vessel out of Cardiff. The ship measured 125’4” (38m) long, 23’4” (7.15m) wide, with a depth of hold of 12’8” (3.9m), the net tonnage was 107, the boiler fitted had a diameter of 13’6” (4.11m) and a length of 10’6” (3.2m). Detailed documentation is available for the ship thanks to the Lloyds Register Foundation Archive, it includes survey reports, classing committee reports, reports on installation of electric lighting and certificates of the ship’s forgings (to name but a few). This rich historical record gives many clues to what might be found archaeologically today.

In 1917 when Miura was completed the First World War at sea was raging, with unrestricted German submarine warfare having a significant impact on vessel losses and the threats from mine fields impeding shipping and fishing. It is not surprising that Miura was requisitioned by the Admiralty for use initially as a minesweeper and then as a hydrophone vessel (fitted with underwater listening equipment that could detect submarines). Fitted with deck guns Miura continued in war service until 1919 when the ship moved to its original intended use fishing out of Cardiff. Reports of shipping movements show that between 1919 and 1927 Miura operated out of Bute West Dock under registration number CF45.

The loss of the ship

What had been expected to be a standard trip began on the 18th March when Miura headed to fish off the Irish coast. The ship was expected to return to Cardiff on the night tide of the 30th March, instead the voyage would end off North Cornwall. On Tuesday night they ran into a dense patch of fog near the coast while there was ‘half a gale’ blowing. The skipper took soundings and gave an order to stop the vessel but didn’t have time to go astern before the ship struck rocks; there were heavy breakers and a swell. From 23.45 the wireless operator sent out an SOS and continued until 00.30 when the wireless mast was carried away.

The crew all donned life jackets and attempted to launch the lifeboat but it was smashed to pieces against the side of the vessel. The ship had heeled over considerably to port. They went to the forecastle having to make their way along the rails on the starboard side that were in the air, some of them lashed themselves to the mast. As the tide rose the crew were washed overboard until there were only five left and the ship was submerged. Two of the five jumped overboard – one was the wireless operator – he reached the shore uninjured but the other was badly buffeted on the rocks and later died.

Mr Kennedy (2nd engineer) reported “We climbed the rigging to the masthead light, and I clung there. We shouted to the others to join Wilkinson, Bridge, Melhuish and myself, but they could not get along. The last person, I think, to go over was the third hand, Thompson. He said ‘I’m finished’, and disappeared. After daybreak we saw a couple of fellows waving to us. Wilkinson dropped over and made for the rocks, and I followed. A big sea came along, and I swam blindly for the shore. I was weak and cold and rolled over and over, striking small rocks all the time. Someone pulled me out.”

The wireless operator, W Page, had made it to shore after being in the water with a life belt for about an hour and a half before the mist cleared and he could see the shore and managed to scramble over rocks. He could not climb the cliff immediately opposite the wreck, but at dawn he was able to make his way up a section of cliff and went in the direction of Stanbury Farm where he was given food and boots and then went on to Woodford where at around 7.30am he made contact with Coastwatcher Hughes. The inquest into the wrecking heard that Hughes had been at his station the night before until 22.00 at which time it was a clear, starlight night with around five miles visibility. As soon as he heard of the wreck from Page, Hughes headed to the wreck and saw the remaining four men in the rigging, he then ran to the watch hut to call the Bude Station to send the rocket apparatus. The remaining men were rescued, although by then were exhausted.

Saved men were: R Bridge, 2nd Mate (Bristol), A. Melhuish, deck hand (Splott), T Wilkinson, deck hand (Grangetown), P Kennedy, 2nd engineer (Roath), W Page, wireless operator (Aylesbury).

Those lost were: M M Joyce, skipper (Cardiff), B Collins, boatswain (Splott), C G Thompson, deck hand (Cardiff), W Metcalf, cook (Grangetown), J Shaw, chief engineer (Grangetown), C Webb, fireman (Grangetown), E Goode, fireman (Cardiff).

This was the worst disaster to have happened in the owners’ firm’s history.

By the 1st April the Salvage Associations Special Officer inspecting the scene reported that ‘the ship has completely broken up and as far as I could see is in three parts, the bow having parted at the forecastle bulkhead and pointing to the eastward. The boiler is on the starboard side and lying at a right angle to the wreck. The after gallows on the port side are visible at low water and the number CF45, can also be read. Under these conditions there is no hope of salvage’.

Searching for the remains

The 30th March 2021 was one of the lowest spring tides of the year (coincidentally occurring exactly 94 years after the remaining sailors would have been lashed to the mast waiting for help), so another trip to Stanbury was planned to see if any remains of the ship could be found. Historic photographs appear to show the ship right out on Lower Sharpnose Point; with the tide dropping it was clear that access that far out on the rocks wasn’t going to be possible and not wanting to become another coastguard statistic caution prevailed and the site was watched from a distance from the beach. As the tide dropped a suspiciously curved looking ‘rock’ began to be exposed and not long after the breaking waves were causing a strange spout of water to emerge from the ‘rock’. Further in towards Stanbury beach than the initial wrecking position the Miura’s boiler was beginning to emerge!

The Miura boiler emerging from the waves (Julie Satchell)

Even with a camera with a reasonably powerful zoom they aren’t the clearest of photographs, but the fixtures on the top of the boiler show it is in an almost upright position. The spout of water must be coming from the ‘man hole’ that would be on the side of the boiler, the water likely entering via the furnace openings (not exposed even at extreme low water) and forced up and out of the boiler casing. Whether there are more remains of the wreck close to the boiler it is impossible to say. An even lower tide and calmer seas might allow a drone survey over the area that would show more. For now, it will remain an intriguing mystery.

One of the anchors from Miura outside Bude Museum (Julie Satchell)

It is possible to get ‘up close’ with part of the Miura. There is an anchor from the wreck which has been recovered and is currently residing outside of The Castle Heritage Centre. With the historical records for the ship giving the exact dimensions of each of the three anchors that would have been carried onboard it should be possible to identify exactly which one this would have been. A task for another day……….