There are many instances of submarines being lost by contact with a naval mine, collisions with other vessels (both accidental and deliberate ramming), surface vessel gunfire, depth charges, aerial bombs, and unexplained circumstances. But a successful attack by one submarine on another submarine is comparatively unusual. MAT volunteer, Roger Burns, investigates two historical examples below.

The First Incident of Submarine Attacks and Their Wrecks: E.3 and U-27

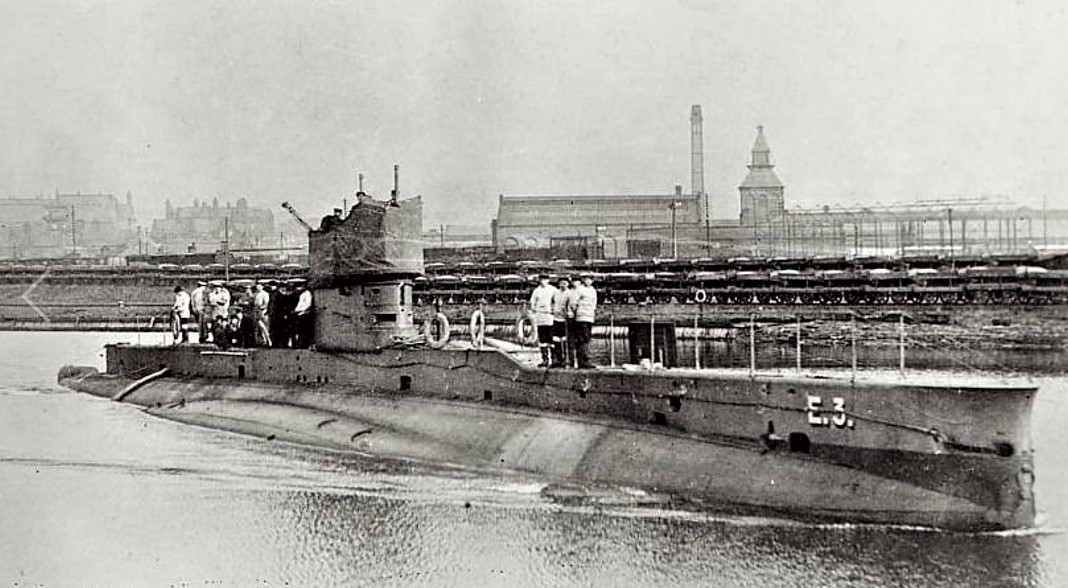

The loss of British submarine HMS E.3 to German U-Boat U-27 early in the First World War on 18 October 1914, is the first recorded submarine on submarine loss and the first submarine loss of the war. British submarines had undergone successive development from the early 20th century as weapons of war. The “E” class was, unsurprisingly, based on the “D” class but modified to include broadside torpedo tubes, which now comprised one bow tube, one stern tube and two broadside tubes, with eight torpedoes on board although E.3, in Group 1 of this Class, was completed to carry ten 18” (c. 45.7cm) torpedoes. Other differences were introduced including two internal watertight bulkheads that provided for the first time an element of internal watertight compartments. After the first eight were built, further modifications were introduced. HMS E.3 is shown in Figure 1.

Submarine E.3

HMS E.3 was built by Vickers at Barrow-in-Furness, laid down in April 1911, launched on 29 October 1912, commissioned on 29 May 1914, and allocated Pennant “83”. The design complement was 3 officers and 28 ratings, but when lost, the number was 3 officers and 25 ratings. The full specification can be read here.

Submarine U-27

German SM U-27 was the first of only four Type U27 Ocean-going diesel-powered torpedo attack class submarines, details of which can be read here. Crewed by a design complement of 35, it was part of IV Flotilla based at Emden, North-West Germany, and had one commander, Kptlt. Bernd Wegener, sinking 11 ships during its service, 10 being British and the first being HMS E.3.

The Attack

E.3 had departed from Harwich on 16 October 1914 to patrol off Borkum, one of the islands off the Ems, Figure 4, northwest German coast, under the command of Lieutenant George Cholmey. Two days later, German destroyers were spotted, but E.3 was unable to manoeuvre into position to attack them; neither could they pass them, so E.3 retreated into the bay until they dispersed. Unfortunately, E.3 did not notice that U-27 was in the bay. U-27 had surfaced, but it had noticed an object resembling a buoy that shouldn’t have been there and consequently dived, suspecting a British submarine. E.3 was not fully dived and its conning tower was visible, showing “83”, its Pennant number. U-27 concluded beyond reasonable doubt that it was a British submarine. Two hours passed while U-27 tracked E.3, until ‘up sun’. Noting that the E.3 lookouts were scanning in the opposite direction towards the Ems, U-27 closed to 300m and fired two of its torpedoes. A hit was registered and E.3 sank immediately. Although four men appeared to be on the surface, U-27 dived in case another British submarine was nearby, withdrew for 30 minutes, then returned. There were no survivors.

The 28 submariners lost on HMS E.3 are commemorated here at the Imperial War Museum Lives of the First World War.

The Wreck of E.3

A fishing boat snagged something in 1990, but it was not until 14 October 1994 that the obstruction was identified as the wreck of E.3. The stern section had been detached in the explosion, indicating that loss of life was immediate. It was later raised. The motor and engine compartments were open and had been looted. The conning tower was raised in fishing nets, and the ladder is said to have been donated to the Royal Navy Submarine Museum in Gosport but is apparently not listed in their official records. The bow section is largely intact.

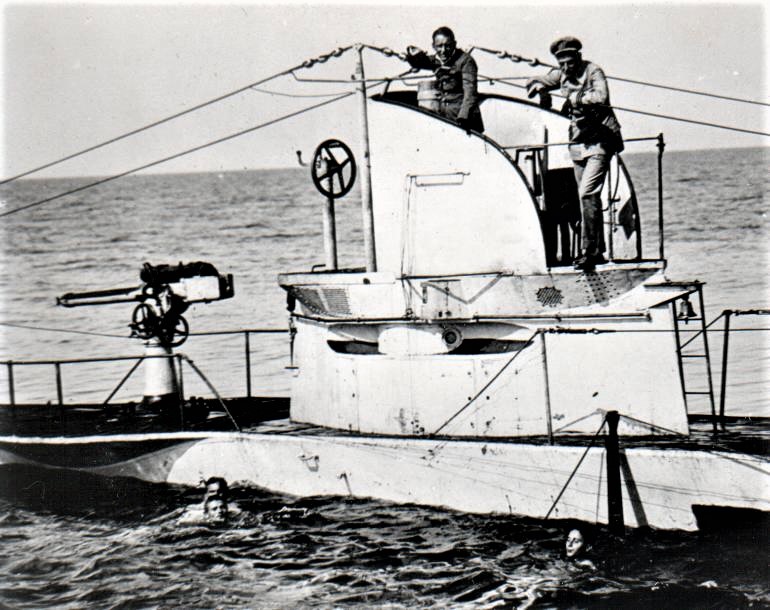

On 19 August 1915, U-27 was sunk by gunfire from the British Q-ship HMS Baralong (Lieutenant Godfrey Herbert RN), which had been roughly equidistant between Cork and Land’s End. Herbert ordered that all German survivors, the commander of U-27 among them, should be executed on the spot. Although the British Admiralty tried to keep this event a secret, news spread to Germany and the infamous “Baralong incident” – a war crime which was never prosecuted – had its share in promoting cruelty at sea.

The Second Incident of Submarine Attacks and Their Wrecks

The second example of a submarine sinking another took place during the Second World War. It is a unique case because it remains, throughout naval warfare, the only known publicly acknowledged example of a submarine, HMS Venturer, sinking another submarine, the German U-864, while both were submerged. It should be noted, however, that Venturer holds another record as it was the only British or German submarine in the Second World War to sink two enemy submarines, U-771 and U-864.

HMS Venturer, allocated Pennant P68, was launched on 4 May 1943 by Vickers-Armstrong Ltd., Barrow-in-Furness, for the Royal Navy. Details about it can be read here. A Schnorchel was fitted to U-864 in October 1944.

U-864, after a 10.5-month training period at Stettin, which lasted until 31 October 1944, was assigned to 33 Unterseeboatsflotille at Flensburg. It immediately went on active patrol with 72 crew, commanded by KrvKpt. Ralf-Reimar Wolfram. It did not sink or damage any enemy vessels before it was sunk by HMS Venturer.

HMS Venturer, Figure 5, exercised from its completion until 8 November 1943 in the area between Larne and Holy Loch. It was then assigned to Lerwick for its first operational patrol. This patrol and the subsequent 12, in which it managed to sink five ships and surfaced German submarine U-771, are described in detail here summarised from official documents.

Note that an image of U-864 or of its sister vessels has not been sourced.

All of Venturer’s patrols were off the Norwegian coast, commanded by Lt. J.S. Launders DSC RN, mainly out of Dundee and Lerwick. It is pertinent to note that Launders was regarded as a first-class officer, and he was awarded the DSC in December 1942 for his actions with the surface fleet before he was transferred to Venturer in April 1943, his first submarine command.

Noted as a fearless and skilful commander, Launders was awarded a Bar to his DSC in July 1944 for “outstanding courage, resolution and skill”. On 11 November 1944, Venturer sunk U-boat U-771 for which he was awarded the Companion of the Distinguished Service Order “for courage, skill and undaunted devotion to duty“. When U-864 was sunk, several crewmen aboard Venturer were decorated, and Launders was awarded a Bar to his DSO. Launders was a ““boy-wonder with a genius for mathematics”, which gave him a tremendous edge in making the necessary vector calculations (manual or minimally mechanical-computer assisted reckoning of speed and trajectories for targets, torpedoes, attacking vessels and currents) that were part of submarine warfare tactics of the day”.

Venturer’s attack on U-864 is narrated in the website highlighted above for the sinking of U-771. The information is log-driven and based on official documents. The location of the attack was about two miles west of the island of Fedje, Figure 6.

The background to the attack and the environmental consequences are important. The British, unknown to the Germans, were able to decipher messages sent using Enigma and had deciphered signals to the Japanese about German Operation “Caesar”. U-864, being a long-distance submarine, was to transport military equipment to Japan with a cargo including 67 tonnes of metallic mercury in 1,857 32kg steel flasks. Japan had been purchasing mercury to be used for explosives, particularly primers, from Italy, but when Italy surrendered in September 1943, some of the supply was with Germany. Additionally, on the cargo manifest, there were also parts and engineering drawings for German jet fighter aircraft Jumo 004, V-2 ballistic missiles, and other supplies. Passengers onboard included a Japanese torpedo expert, Tadao Yamoto, a Japanese fuel expert, Toshio Nakai, and two German Messerschmitt engineers, Riclef Schomerus and Rolf von Chlingensperg.

The decrypted messages contributed to HMS Venturer being sent to intercept U-864 in the Fedje area. Venturer failed to find the German submarine, which had passed the Fedje area, but misfortune for U-864 would be a stroke of luck for Venturer, when one of U-864’s diesel engines started misfiring. Faced with a long journey, KrvKpt. Ralf-Reimar Wolfram decided to return to Bergen for repairs and a signal was sent confirming an escort would meet it at Hellisøy, Fedje. The noisy diesel engine was heard as hydrophone effect aboard Venturer and, in due course, U-864’s periscopes were spotted. Launders decided to turn off his active sonar to minimise chances of detection by U-864. Then, using his “genius for mathematics”, armed four torpedoes to run at different depths in a spread calculated in 3D terms that, at the time, had not previously been used in combat situations. U-864 heard the incoming torpedoes so dived and turned away, but it unknowingly steered into the path of one of them and, following an explosion, sank. 32 minutes after the explosion, Venturer encountered oil and a floating cylinder. All 73 on board the U-864 perished. All German submariners who died in conflict are commemorated at the U-Boot-Ehrenmal Möltenort at Heikendorf near Kiel.

HMS Venturer underwent a refit when the war with Japan ended. It was then sold to the Royal Norwegian Navy and renamed Utstein. It was finally broken up in 1964.

The Wreck of U-864

Local fishermen alerted the Norwegian authorities when their nets encountered an obstruction and the Royal Norwegian Navy found the U-864 wreck in March 2003. An ROV survey in August 2003 located multiple pieces of debris and the mercury was found to be leaking with the propensity to cause a major environmental disaster by mercury poisoning. An attempt to salvage the canisters failed as the wreck was unstable, but one of the steel canisters was recovered and found to be corroding. A three-year study followed and in 2008 a contract to recover the wreck was awarded. This was later halted when the Norwegian government asked for further studies. The Norwegian Coastal Administration decided in October 2008 to entomb the wreck, a feat that could be carried out safely using proven technology. Further environmental aspects of the wreck can be read here and here. Images, subject to copyright, can be viewed here.

We hope you enjoyed exploring these two unusual cases of submarine attacks and their wrecks. If you would like to explore vessel losses involving sea mines, you might enjoy reading another of Roger’s articles on ‘Naval Sea Mines to 1919’.