As part of our recent series of blogs on Bouldnor Cliff, MAT has been exploring how divers qualify to dive for work, and the methods recently used to take samples at the site. Now, MAT’s Project Officer, Carley Divish, shares her research on the lithic collection.

I have experience diving in all conditions, from freezing Indiana lakes and caverns to clear-as-glass Caribbeans waters. Diving in Bouldnor was new. The currents were surprising, and switched with the tides, the pace of work was fast, and using heavy tools underwater sucked my air away. However, it was all worth it. And honestly, what is a dive without a bit of a challenge? The water was clear, the currents kept the silt of our work away, and the drysuit kept me nice and warm! The other volunteers were just as excited as I was to venture into the unknowns of this project, so the boat was cheerful.

When I came to the UK to do my Master’s Degree at the University of Southampton, I knew I wanted to research submerged landscapes. In the States I worked with shipwrecks, museums, and archives, but being from Indiana, a landlocked state, there was not much coastline to work with. Oceans do not rise in the middle of the plains. In Southampton there was much more opportunity than I had even considered. My time at the University taught me a lot, mainly about something I never thought I would be interested in: lithics. This led me to volunteer with the Maritime Archaeology Trust on Bouldnor Cliff, and eventually focus part of my dissertation on the lithic collection.

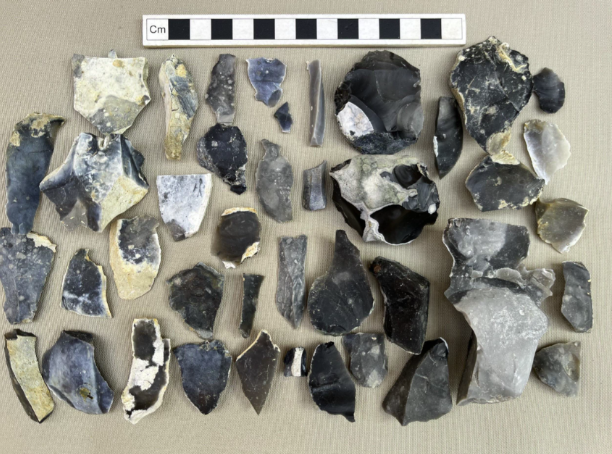

Figure 1: 2020-21 Bouldnor Lithic Collection oriented by location, Source: Maritime Archaeology Trust

If you aren’t a niche archaeologist, lithics are stone tools. Easy enough, right? You’d think, but the hard part is identification when most evidence is debitage, or the flakes that come off the larger core when making a tool. If you think about it, you have to create hundreds of flakes to create one final product!

The lithics at Bouldnor Cliff are unique, though. It is more than the fact that they have been submerged for thousands of years, it is also the erosion of the cliff. The Mesolithic site has gone through periods of exposure to air and submergence again, but right now it is fully submerged, no doubt about that. The cliff that the lithics are in is eroding, with the currents and lobsters removing sediment and stone tools falling out onto the sea floor. This means that they are ‘out of context,’ or that the soil layer they were originally in is gone. Because of that, the lithics lose a lot of information that archaeologists would love to know, all coming from the dirt.

Figure 2: Reconstruction of life at Bouldnor during the Mesolithic, Source: Painted by Mike Greaves

However, the lithics have been collected since the project began in the 90s with documentation of their condition and display in the Shipwreck Centre. There is so much information we can use to understand how they were made, how they moved underwater, what people used them for, and so much more. Furthermore, because the lithics are so sharp, we can tell that they haven’t moved far. Even through the strong currents and silty sea, these small rocks hold strong, cemented down by sediment and tiny crabs. This means that their location still likely has significance, even though the soil is gone. What that tells us, I’m not yet sure, but it is a strong step forward!

During my second dive on the site this past summer (BCII for those in the know), Garry Momber, the Director of the MAT, took me aside, telling me we were going to see the lithics, the things I was focusing all my energy on studying! We jumped in the water, swam past everyone else working, and eventually made it to the place. His flashlight illuminated hundreds of rocks on the sea floor, and I have to admit, even after all my study, it took him picking up a few lithics and showing me the evidence for me to understand what I was looking at. Lithics were EVERYWHERE. And they were all so sharp! I began collecting a few, careful to only take the ones I was sure of, documenting where I had found them. Some of the tools looked like I could pick them up today and start cutting some rope. I placed them in the archival quality bags, ready to check out again on the surface, labeling where I had found them. When the dive ended, I was nervous but excited! I had seen exactly what I was spending all my time researching! When we got unsuited on the boat and I finally got to expose the tools to the fresh air, I was not disappointed. I had found lithics for the first time, something tangible to add to my own research and help continue the work on this site.

Figure 3: Lithics collected June 2024 from BC II , Source: Maritime Archaeology Trust

The Mesolithic period dates to around 12,000 years ago, and these tools still remain as fresh as the day they were dropped. It was an awe-inspiring feeling to know that I was the first human to touch these since they were left so long before. I know studying rocks is not the most interesting pursuit in the world, but to me these tangible elements of early human life are worthwhile not only in the information they can tell us, but also in the connection they create to the past.