Volunteer Roger Burns investigates the sinking and subsequent raising of a Royal Navy Cruiser, HMS Gladiator, consequent on a collision in the Solent with an American passenger liner, SS St. Paul. Raising ships, especially such a large ship, was unusual then and a considerable feat. A decade later, a bizarre sequel unfolded.

HMS Gladiator & SS St. Paul

One of four Royal Navy Arrogant Class Protected Cruisers and one of the last Ironclads, Gladiator, Figure 1.A, was built at Portsmouth Naval Dockyard, launched on 18 December 1896, and completed in April 1899. It was iron hulled, 104.2m long, with 17.5m beam and 6.4m depth, a surface displacement of 5,750 tons, with armament of 10 x 6ins, 9 x 12pdr, 3 x 3pdr, 5 x machine guns and 2 x torpedo tubes, protected by deck armouring 76mm thick. Propulsion comprised 2 x triple cylinder expansion steam engines, 18 x Belleville water tube boilers, capable of 19 knots driven through two screws. Most of its service life was spent in the Mediterranean with other warships, often returning to the UK.

Figure 1.A: HMS Gladiator Undated, Source: Symonds & Co., Public Domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Figure 1.B: SS ST Paul c. 1911, Source: 1911 Encyclopaedia Britannica, Vol. 24, pg. 888, Plate VII via Wikimedia Commons

The SS St Paul, Figure 1.B, was launched on 9 April 1895 by W. Cramp & Sons of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania for the American Line as a trans-Atlantic ocean liner. Steel hulled, 11,629grt, 168.9m long, with 19.2m beam, it was powered by quadruple expansion steam engines and two screws, also capable of 19 knots. With accommodation for 1,370 passengers, the St Paul departed New York for its maiden voyage on 9 October 1895 to Southampton.

The Collision 25 April 1908 & Rescue

A particular feature was the weather, with heavy snow as recounted here. The St. Paul, now owned by the International Mercantile Marine Company, New Jersey, and with a Trinity House pilot, had departed Southampton at noon with 168 passengers and 362 crew for New York via Cherbourg and sailing down Southampton Water, turned by Calshot to starboard along the western Solent, experiencing transient snow showers. Meanwhile, the Gladiator was returning from the Long Sands range near Dartmouth, via Portland for Spithead then Sheerness, passing the Needles to use the western Solent. The Gladiator had just passed east of the pinch point by Hurst Castle, enveloped in a thick snow fall, with poor visibility, at 9 knots. There was a flood tide, a Force 6 to 7 NNW wind, and the St. Paul was proceeding at about 9 or 10 knots. They saw each other at about 0.5 miles apart, and both ships continued and realised they were on a collision course. The St. Paul stopped engines, then helm was put hard aport and the starboard engine full astern, the two ships should have passed port side to port side but the Gladiator starboarded, expecting the St. Paul to put helm to starboard but it did not, its bow striking Gladiator amidships on the starboard side, cutting well into the Gladiator’s side, entering No 5 bunker, bursting the bulkhead into No 6 and cutting through the upper deck nearly up to the funnel casing, a hole of about 6mx12m. The collision was at about 14.35, and although the closing speed had been high, it was a glancing blow.

Figure 2: West Isle of Wight – Sink position of the Gladiator, Source: Maritime Archaeology Trust

As agreed with Gladiator’s master, Captain Walter Lumsden, the St. Paul reversed its engines, broke free and water surged into the Gladiator which turned towards the Isle in order to beach but in under 10 minutes capsized and came to rest on its starboard side about 230m off Sconce Point, Figure 2. The St. Paul used five of its lifeboats to give assistance to those of the Gladiator crew in the water, then, with its buckled bow, returned to Southampton without any casualties, effected repairs at Portsmouth and some weeks later resumed operations.

The Gladiator, rolling so quickly, threw sailors into the icy water, causing only a few of its boats to be launched. Some sailors swam ashore, some returned to the ship which was above water, and there are many media reports of gallantry and loss. A company of the Royal Engineers was playing billiards in the nearby Fort Victoria, including Lance Corporal Poole, when they heard the crash, and seeing the ships parting, assumed it not serious but then seeing Gladiator rolling over, rushed down to the beach, two soldiers jumping into the single available boat, rowing to the ship. Poole heard the cries of sailors struggling in the cold water, stripped off all his clothes and swam out three times, saving one sailor each time. All the soldiers contributed to the rescue but, of 450 onboard which included supernumeraries including additional stokers while Gladiator was engaged on gunnery duties, 28 lost their lives. Nine injured survivors were taken to Golden Hill Fort hospital and many coffins were despatched from Haslar hospital. Noteworthy contributions to the rescue were made by the Coastguards and, throughout the rescue and subsequent salvage, by the Royal Engineers from Fort Victoria.

Figure 3:The Gladiator wreck.

3.A: Clockwise bow, stern and a propeller, Ref. NETCC : P.1986.1283.47;

3.B: Crew removing light articles, Ref. NETCC : P.1986.1600;

3.C&D: Before salvage starts in earnest, Refs NETCC : P.1986.1630 & NETCC : P.1986.1634. Source: Kind permission of Carisbrooke Castle Museum.

On hearing of the disaster, the Admiralty immediately mobilised battleship Formidable, cruisers Berwick and Forte, plus naval tugs Malta and Enterprise to the scene, more vessels following. Navy divers quickly conducted salvage duties, primarily to find bodies, and collected ships documents and personal items such as golf clubs, sporting guns, and other effects. No bodies were found but Mickey, a black and white ship’s cat, was found, terrified, but calmed when recognising one of the ship’s crew.

Awards

On 16 July 1908, a silver medal was awarded to Royal Engineers Cpl. G. Stenning, and bronze medals to LCpl Poole and Sgt Makot Creeth by the Royal Humane Society in recognition in saving lives on 25 April. On 17 August 1908 at Fort Victoria, Admiral Sir A. Fanshawe, having identified that the soldiers needed a boat, presented to the 22nd Company, Royal Engineers for bravery during rescue, and attending to needs of those rescued, the undamaged gig from the Gladiator with a plate suitably inscribed affixed to the gig backboard.

Salvage & Raising Gladiator

Naval authorities decided to appoint the Liverpool Salvage Association who had just salved HMS Montagu at Lundy to recover Gladiator. The Association’s chief salvage officer, Captain Frederick H. Young, was placed in charge, using one of their salvage vessels, Ranger, originally a naval gunboat, assisted by several naval vessels and lighters. The salvage proved to be one of great difficulty despite his broad experience.

The wreck was lying on the edge of a bank near deeper water, so initially shore works were built, partly to hold the wreck in place in case the strong currents and storms moved it but also to help righting it. These works comprised strengthening the shore, providing two bollards, Figure 4.C & D set in concrete, and two powerful steam engines, Figure 4.B. Cables, comprising Bullivant & Co’s galvanised special extra flexible steel wire, were taken from the shore works and affixed to the wreck. Use was made of the now derelict Fort Victoria pier, Figure 4.A which is just visible in Figure 4.C. The shore stabilisation, comprising stone in gabions, in Figure 4.C may be more recent, photographed in 2006.

Figure 4: Shore Works.

4.A: Fort Victoria pier. Source: The old pier near Fort Victoria by Steve Daniels, CC BY-SA 2.0 via Wikimedia Commons

4.B: Two engines embedded in concrete, 09/1908, Ref NETCC : P.1986.1669. Source: Kind permission of Carisbrooke Castle, Museum, Ref. NETCC : P.1986.1669;

4C&D, remains of bollards. Source: Kind permission of Alan Stroud, 2006.

In parallel with the shore works, salvers started removing accessible superstructure works to lighten the wreck, moving onto underwater items, but the divers’ hours were severely limited due to the strong currents. Several vessels were involved, big pumps, Figure 5.C, were employed and large pontoons 33m long x 3m diameter, Figures 5.D to 5.F, were affixed to the wreck in an effort to float it. Additionally, 200 tons of ballast were placed on the port bilge, by early September compressed air was being pumped into the pontoons and the wreck was sufficiently afloat to close the gaps in the hull.

Figure 5: Salvage Operations. 5.A: Multiple resources deployed,

5.B to E: progressive stages,

5.C on 2/10/1908, E on 1/10/1908, D on 8/09/1908. Source: All with kind permission of Carisbrooke Castle Museum. Refs: A-F are NETCC: 2013.487.46, NETCC : P.1986.1681, NETCC : P.1986.1661, NETCC : P.1986.1601, NETCC : P.1986.1653, and NETCC : P.1986.1668.

Sconce Point to Portsmouth and Repair Decision

It was originally thought that recovering the wreck would be relatively quick but it was not until early October that the wreck was sufficiently upright and watertight to contemplate it being moved.

Figure 6: The Final Stages.

6.A&B being towed en route to Southampton, 3/10/1908.

6.C&D docked at Portsmouth, 7/10/1908,

6.E pumping out in dock,

6.F the damage to Gladiator. Source: All Carisbrooke Castle Museum, Refs A to F are NETCC : P.1986.1671, NETCC: 2013.487.106, NETCC : P.1986.1665, NETCC : P.1986.1675, NETCC : P.1986.1682 and NETCC : P.1986.56

By 1 October, the wreck was as nearly watertight as possible, bulkheads closed and on 3 October, over five months work culminated in final floating, albeit with a slight list to starboard, and at 12.25 with four tugs, Gladiator set off for Portsmouth, Figures 6.A & 6.B, expected to arrive at 16.00. Despite calm conditions, it actually took six hours for the 20 miles, and on arrival, despite pumping, had settled about 60cm lower in the water. Dry docked, Figures 6.C to 6.E, the damage really became apparent, Figure 6.F.

Salvage cost amounted to £64,000, and assessed as beyond economic repair, the wreck was sold in March 1909 for £15,125 to Messrs. Hendrick Ido Ambrecht, a Dutch shipbreaking firm, with a £500 contribution by the Admiralty to make it seaworthy for the tow to Holland. (2023 prices are approx. £6.3m, £1.5m and £50k)

Seabed remains

Guns and fittings were largely removed during salvage but there is material in the area on the seabed picked up by side scan that is thought to be related to the remains of the vessel but the area is not normally dived due to the strong currents. Believed to have come from the Gladiator, a pen and inkpot stand was found on Isle of Wight’s south coast.

Court Martial and Admiralty Court

Both actions which overlapped heard differing evidence and the Admiralty court judgement was delayed pending the Court Martial to avoid prejudicing the latter.

On 12 June 1908, the Court Martial found Captain Lumsden guilty of hazarding the ship by default, but not by negligence. The Admiralty court concluded that the Gladiator was to blame for the collision, confirmed on appeal in December 1908, and in February 1909, the owners of the St. Paul claimed compensation for damages of about £25,000 (c. £2.45m).

SS St. Paul 1908 and 1918

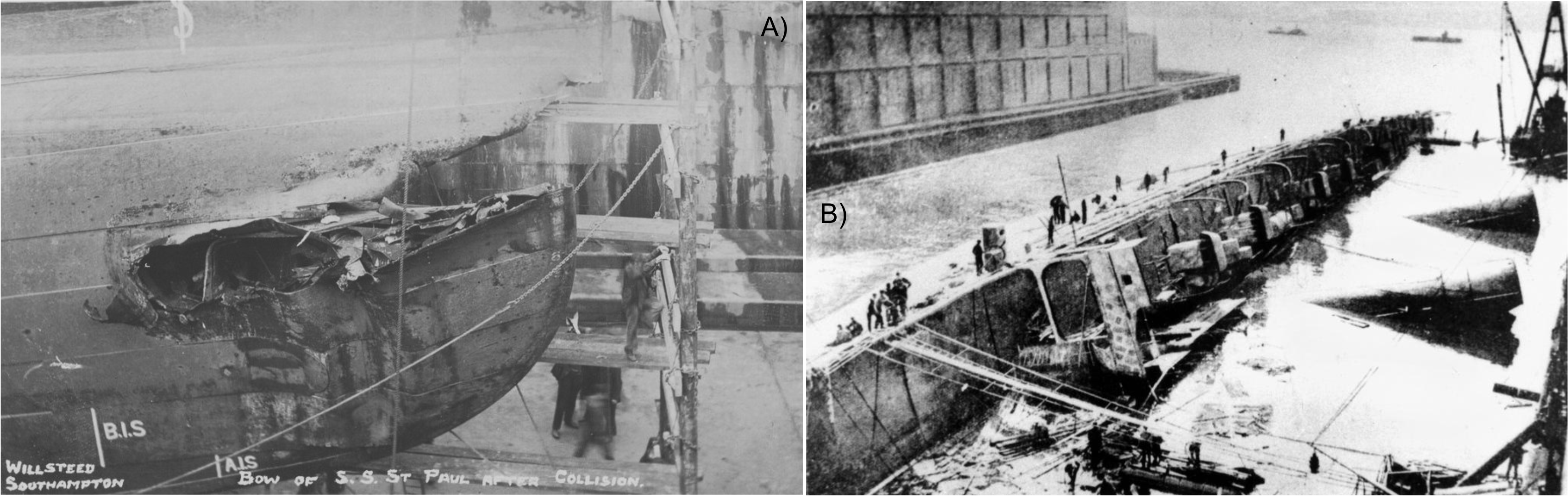

Figure 7.A: Damage revealed at Southampton, 1908, Source: Kind courtesy of Carisbrooke Castle Museum, Ref NETCC : P.1986.1604.

Figure 7.B: Capsized in New York Harbour, 25/04/1918, Source: Public Domain via Wikimedia Commons

The extensive damage to St. Paul’s bow, Figure 7.A was repaired, returned to service and in April 1918, it was commissioned as a troop transport. Renamed as USS Knoxville, it arrived after conversion at Pier 61 in New York where it capsized and rolled over, Figure 7.B. Bizarrely, it was 25 April, exactly 10 years since Gladiator rolled.

Model of Steering Gear used in the Gladiator

The Science Museum in London have a working, scale 1:4, model of Bow M’Lachlan and Co’s steam steering gear as fitted to the Gladiator. The following images were specially and generously provided to MAT by the Science Museum.