When thinking about the First World War it can be easy to view the maritime activities as solely those of warships. But many other vital operations were carried out by merchant and auxiliary fleets. Work experience student Noah looks into these civilian vessels and their valuable contribution to the war effort.

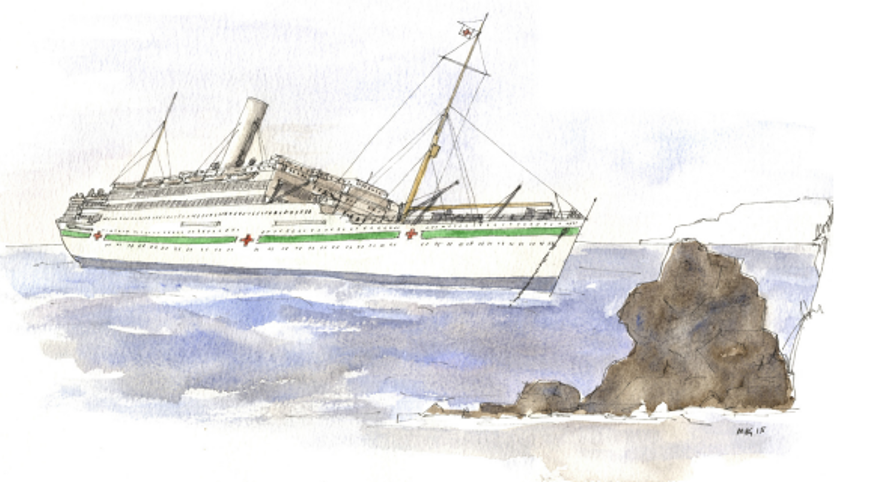

Commercial ships, such as passenger ships or postal ships, made up one of the most important forces in the Great War for a variety of reasons. Many of the steamers operated as hospital ships, as they could provide large amounts of space for the injured, necessary with the conflict raging on the Western Front. Hospital ships could quickly travel to and from the mainland to bring casualties to England. At the start of the war, they were marked in green stripes and red crosses, over a white painted hull, to conform to the Hauge convention. These marks indicated to enemy ships that the passengers on the vessel in question were wounded and should not be attacked. However, after Germany declared it would begin indiscriminate attacks on all vessels in the English Channel, marking hospital ships fell out of fashion, as it made them an obvious target. In fact, just a month after the declaration of all out war, the hospital ship HMHS Asturias was sunk, leading to many patients being thrown into the sea. Similarly, two years earlier, another hospital ship, HMHS Anglia, was sunk by a mine. Quickly, a rescue effort was launched, and at least two steam ships arrived at the scene, along with naval and other ships. They made great efforts to save the patients of the Anglia. Unfortunately, however, one of the rescuing ships hit another mine, causing even greater disaster. In the end, there may have been as many as 230 lives saved, from an original count of at least 390, but the numbers are understandably difficult to verify. And there we find the second job of civilian ships: Rescue. You can head MAT’s YouTube channel to hear more about the heroic stories of nurses aboard these ships.

Figure 1: HMHS Asturias, Source: painted by Mike Greaves

During the First World War, over 4,000 British vessels were sunk by U-Boats. This campaign was massively destructive and caused huge loss of life, but many lives were saved by the efforts of captains of both civilian and naval vessels. You can find more detail on how U-boats operated in the Great War Shipwrecks booklet created for the Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War project. But ships weren’t just carrying the wounded and rescuing stranded sailors. With a war on a scale that had never been seen before raging in Europe, industry had to kick into full action. Many of the resources for manufacturing had to be transported into France by sea, as Germany blocked transport over land. To accommodate this, Britain, just across the channel, sent many ships to the continent. Fifty-eight percent of British ships lost were merchant vessels. Only ten percent of lost ships were naval vessels. Merchant ships carried all sorts of resources: from coal and brass to soldiers and passengers. Ships ranged from steam liners like The RMS Lusitania with crews of 850, to small sail boats such as the Little Mystery, a two masted schooner with just five crewmembers. Sailing out of Fowey in Cornwall, it traded across the Atlantic with America. However, in 1917, the French government sent out a call for coal, due to shortages with production. In response, Little Mystery among, many others, began to bring shipments of coal to France. However, like so many ships of its time, without a convoy to protect it the ship was discovered by a German U-Boat and captured. Eventually, after scouring the ship for food, and allowing the crew to evacuate and bring some possessions off, the German crew detonated a bomb on the ship and it sank, just off the southern coast of England. After this event, schooners were added to the boats put in convoys to France, saving many other small boats from a similar fate. But how were these convoys protected? Traditional naval vessels were certainly instrumental to staving off U-Boat attacks, but repurposed civilian ships also played a major role in the defence of convoys, and in destroying U-Boats in the channel.

Figure 2: German U-boat UB 14 with its crew, Source: Wikicommons

The term Q-Ship came about in 1915, and were vessels purposefully designed to look like a Merchant ship. The admiralty needed some method to stop the German submarines from damaging British and Allied shipping anymore than they already had. Convoys of ships, whilst effective, were deemed to resource intensive, and were not considered an option for the navy. Because depth charges of the time were ineffective, only gunfire or ramming could assuredly destroy a U-Boat, meaning an armed vessel had to be used. However, this was only effective if the submarine was above the surface, so some method of making the submarine surface had to be utilised. Torpedoes were expensive, and submarine captains were only willing to use them if absolutely necessary, preferring the much cheaper cannons. So how could they get a submarine to attack an armed vessel? Submarines would not surface around a naval ship, as that would mean certain destruction. So rather than sending out dedicated warships to hunt for submarines, civilian ships such as steamers would be fitted with guns and sent into areas where U-Boats were known to be operating to draw out an attack. When U-Boats surfaced, Q-Ships could bring multiple cannons to bear, overwhelming the submarines one. However, the ship would have to identify its actual purpose as a vessel of war before firing any shots. So, when shots were fired, the flag of the Royal Navy had to be hoisted, warning the enemy of their nature. Around 200 Q-Ships were utilised during the war, with twenty-seven to thirty-eight lost. They sunk around twelve to fifteen submarines. You can read about other Q-ships such as the HMS Bombala in the Hollybrook Memorial booklet created for the Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War project.

In conclusion, civilian ships were vital to the Allied war effort. Without them, shipping, troop transportation, and even treating the wounded would have been impossible, and the crews that sailed these ships should be recognised as the heroes they are.