A total of six steam powered lifeboats for the Royal National Life Boat Institution (RNLI) were built and put into service by the RNLI between 1890 and 1900. MAT volunteer Roger Burns takes us through the background behind the introduction of these craft, describes two very different propulsion systems, summarises their service histories, and touches on the reasons behind only six being procured over a ten-year period.

Background

From its beginnings in 1824, the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck became in 1854 known as the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. These lifeboats were sail and oar (oar was also called pulling) propelled, and this means of propulsion lasted at some locations through both World Wars until 1948. These craft, with the volunteer crews, not only saved lives from ships in distress but on occasion succumbed themselves.

The Globe of 30 June 1871 carried a report about a meeting of the influential committee of the Steam Lifeship Fund, as it was then called, and after discussing finances, turned to an important topic, the “construction of a powerful vessel, to be propelled by steam, and to be exclusively devoted to saving human life”. Comparisons were made between significant improvements with the adoption of steam, citing hand-operated fire appliances v. steam fire engines, and sailing vessels v. steamships. But progress in realising this ambition was punctuated with caution and realism, to ensure constructive and effective use of RNLI finances, a voluntary funded organisation then as it remains today. The Quarterly Journal of the National Lifeboat Institution gave reasons why steam power was not considered viable: many examples of current lifeboats being launched from a beach through surf, the violent motion experienced in storms, and the difficulty of finding and expense of training crew with knowledge of steam engines as current volunteer crews were drawn from competent fishermen and sailing vessels. A reaction to this report by John Fellowes was included in the Journal Springer Nature, (181-182) airing his opinion that a screw or paddle powered lifeboat would be disastrous!

In May 1886, a RNLI sub-committee was tasked with examining the practicability of applying steam to Lifeboats; the sub-committee examined models of steam powered lifeboats at the Liverpool International Exhibition – a huge exhibition – and concluded nothing had convinced them to adopt any type of steam lifeboat. But pressure to evolve in applying mechanical power to lifeboats led to the RNLI offering gold and silver medals for drawings and plans suitable for steam lifeboats, which attracted entries from Europe and America. Again, examined by three independent experts, none were deemed to satisfy the requirements of the RNLI. At one point, electrical power was considered using accumulators but the enormous weight quickly ruled it out.

In early 1888, Blackwall shipbuilders R&H Green submitted a proposal to the RNLI who, with their professional advisers, negotiated an acceptable package which was approved and the go-ahead for construction was given for a steam powered lifeboat. Negotiations had been aided by a model built by Greens. The propulsive effort was not a screw propellor, and not paddles which were clearly unsuitable, but a then controversial “hydraulic” or “turbine” system, despite this system needing more power via a large engine and boiler and therefore more coal than a screw for comparable speed. The screw was deemed to be unsuitable for shallow waters, the sometimes violent motion of the boat through rough seas thus exposing the propeller thereby racing the engine, and obstructions as floating wreckage or ropes tangling with the propellor. The adopted alternative solution was an inlet on the bottom of the hull connected to a powerful centrifugal pump, (a turbine) whose discharge was piped to front and rear hull outlets, these variably directed outlets being easily controlled via deck operated valves to vary the direction of discharge of the water jet, greatly aiding manoeuvrability, without the need to juggle power from the engine. The exiting water jet stream(s) simply thrust the boat in the direction needed, on the principle that to every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. At full speed, it was estimated that one ton of water per second entered the intake. During trials, experiments were undertaken by artificially introducing various types of debris, including ropes, sails, and wood which showed that the intake operated satisfactorily without ingesting anything but there was recognition that only real-life rescues would prove the concept. It was also recognised that steam lifeboats would only be possible at a limited number of sites, those where it would be moored afloat, as launches from beaches, slipways or transporters were impractical. There was concern at the higher capital and maintenance costs.

Joseph Green from the London Blackwall Yard exhibited a patent 1-inch scale model of the hydraulic lifeboat at the 1893 Chicago exhibition.

Duke of Northumberland Lifeboat

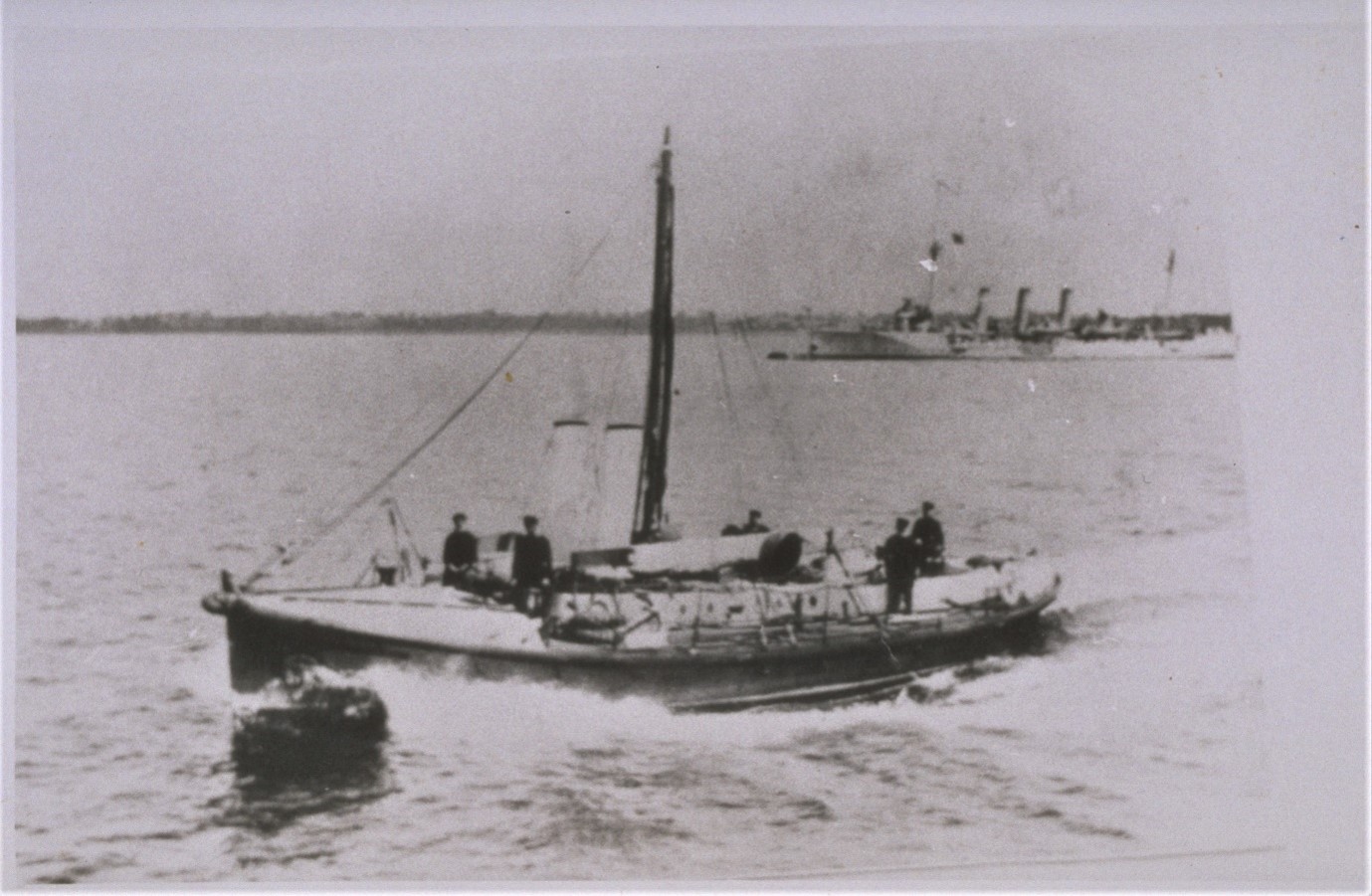

A series of trials in early August over the measured mile at Maplin, the Duke of Northumberland, Figure 1, named after one of the RNLI’s keen supporters loaded to replicate its service condition, realised a mean average speed of 9.171knots. After testing, Harwich Lifeboat Station in September 1890 received this first steam lifeboat in active service. It was soon in action the following month and “behaved admirably”, as reported in the Morning Post of 21 October 1890.

Figure 1: Duke of Northumberland Lifeboat. Undated. Source: RNLI. Kind permission of the RNLI/Graham Farr Archive

The lifeboat’s hull was of best quality steel, the plates being triple rivetted together with 72,000 rivets – torpedo boats of the period were double rivetted – without a single continuous seam, in order to counter the stresses smashing into waves, whereas other steel hulls were single rivetted. It was not self-righting beyond 110°, the mast being 20° below the horizontal, but featured modified end boxes designed similarly to self-righting vessels, and contained fifteen water tight compartments, bilge pumps and steam ejectors. 15.24m long with overall beam of 4.36m and 1.07m deep, including a flush deck with inset accommodation for up to 40 persons, it was powered by twin horizontal direct acting compound steam engines complete with one boiler and at full speed, a 1,000-rpm fan created forced draught, and it had twin funnels. Recognition must be given to the fortitude of the engine room crew including stokers of these steam lifeboats when being tossed around in storms but the forced draught would have provided ample ventilation. A fuller account may be read here.

This lifeboat was transferred in 1892 to New Brighton temporarily then was based at Holyhead – there, in 1901, while on passage, a boiler room explosion killed two firemen. It was retired from service in 1928.

City of Glasgow Lifeboat

Launched in 1894 by Greens of Blackwall, the City of Glasgow lifeboat, Figure 2, similar to the Duke of Northumberland, arrived at Harwich on 7 November 1894 where it remained until sold by the RNLI in 1901. It was so named as it had been funded by the Glasgow Lifeboat Saturday Fund.

Figure 2: City of Glasgow Lifeboat. Undated. Source: RNLI. Kind permission of the RNLI/Graham Farr Archive

Queen Lifeboat

This steam water jet lifeboat served at New Brighton Lifeboat station between 1897 and 1923. Built by Messrs Thorneycroft of Chiswick, it was 16.76m long with 4.88m beam and 0.9m draught displacing 30 tons, could accommodate 40 passengers, had a crew of nine, and unlike the first two steam vessels could burn coal or oil in the 200ihp steam engine, and was regarded as then being the largest lifeboat in the RNLI fleet. The Duke of Northumberland and the City of Glasgow each carried 30 hours supply of coal, whereas the Queen carried 60 hours supply of fuel from three tons of coal and two tons of oil. The water jets could move 60 tons/hour of water.

It travelled via Grangemouth and the Forth & Clyde canal to New Brighton, pausing at Harwich for trials, briefly visited Douglas, and arrived at New Brighton in October, succeeding the Duke of Northumberland although it was not formally handed over until December. Eventually it was sold in April 1924 to a private buyer who had intentions to use it for local cruises.

City of Glasgow II Lifeboat

This lifeboat was built by J. Samuel White of East Cowes, and was 35 tons grt, with 200 ihp steam engine. It arrived at Harwich on 11 May 1901 and had a tunnelled screw. Records disappear after 1916.

James Stevens No. 3 Lifeboat

This lifeboat, Figure 3, also built by J. Samuel White of East Cowes for the RNLI, was launched in 1898 and arrived at Cleethorpes in October 1898. It was 57 tons grt, its engine developed 220ihp and featured screw propulsion. In January 1903, the vessel was transferred to Gorleston. On 15 and 16 January 1905, the Chief engineer, Charles James Sclanders and the coxswain Harris were awarded silver medals for conspicuous merit and gallantry saving life from the Celerity off Hopton. The Norwich Mercury of 8 April 1905 quoted Sclanders in his reply speech said “he was air-tight down below when on board. Those on deck did not know what was going on below, and he, of course, did not know what was going on on deck. They had one another’s lives in their hands”.

Figure 3: James Stevens No 3 Lifeboat. Undated. Source: RNLI. Kind permission of the RNLI/Graham Farr Archive

The James Steven No. 3 was until 1908 at Gorleston lifeboat station No 4 when it was transferred to Angle lifeboat station. On 6 March 1908, while at Newquay, en route, it was launched for practice in rough weather and returning, a huge wave overturned it twice, with the loss of one crew, all of whom had been swept overboard on both occasions. At Angle it broke from its moorings, and, damaged on rocks, was withdrawn in 1915. However, the James Stevens No 3 was then stationed at Totland on the Isle of Wight until 1919, and after participating in the great river Thames Pageant procession celebrating one years’ peace, transferred to Dover which had reopened after closing in 1914 due to manning problems, due to the war but it closed again in 1922.

James Stevens No. 4 Lifeboat

Also screw driven and built by J. Samuel White, the James Stevens No. 4 lifeboat similar to No 3 arrived at Padstow on 21 February 1899. On 3 September 2009 during a heavy north westerly gale, eleven of the 14 crew were lost when a huge wave overturned the vessel when en route to the aid of fishing boat Peace and Plenty which had got into difficulty drifting towards rocks at Hell Bay. The lifeboat ended upside down among the Trebethevick rocks. Padstow was home to two lifeboats, the other being oar powered which had also gone to help, but the heavy seas defeated it with the crew saved. Three of the Peace and Plenty were lost, the remainder being saved by rocket apparatus.

J. Samuel White built one more steam powered lifeboat, the Lady Forest, which was stationed from 1903 in Fremantle Western Australia acting as a pilot boat.

Petrol Driven Lifeboats

By 1900, development of steam powered lifeboats had ceased, partly due to capital and maintenance costs. Petrol engines had been undergoing development, improving reliability which led to them being trialled in oar and sail lifeboats, notably in the Solent in 1904. One year later, the petrol driven J. McConnell Hussey lifeboat was built and stationed at Tynemouth Lifeboat Station. Initial doubts from the crew were overcome, as this lifeboat provided better power and control. Diesel engines followed and apart from the operational benefits, provided for enhanced volunteer recruitment.