Volunteer Jane Thakker explores the story of the Thomas W Lawson, a vessel researched as part of the Metal Huller Sailing Vessels project. When it was destroyed by a storm in 1907, it became one of the first large marine oil spills.

The Thomas W Lawson on its maiden voyage. Source: Schooner ‘Thomas W. Lawson’ 1902-1907a – Thomas W. Lawson (ship) – Wikipedia

In December 1907 the Lloyd’s agent on the Scillies telegraphed to say that oil was floating on the water, at the position occupied the previous night by the American schooner, the Thomas W Lawson, the lights of which had disappeared at 2.50am. The ship had been on its maiden Transatlantic voyage carrying 6,000 tons (2,225,000 gallons) of light paraffin oil and became the source of the world’s first major oil spill.

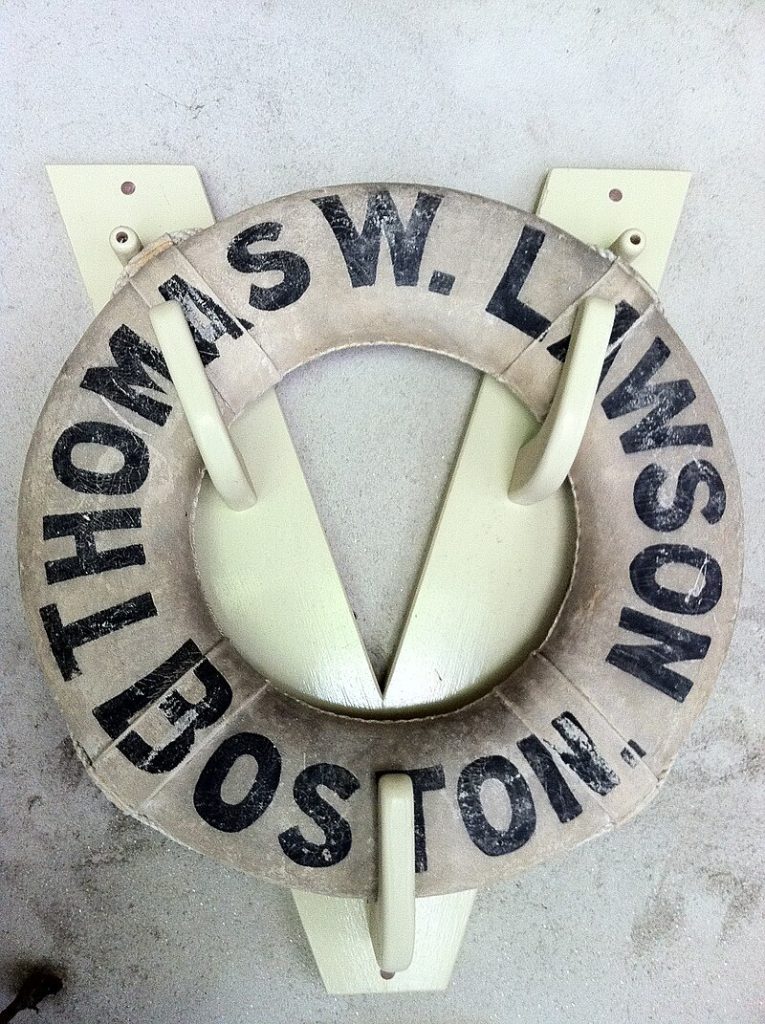

The Thomas W Lawson was built in 1902 in Quincey, Massachusetts, by the Fore River Ship and Engineering Company for Coastwise Transportation of Boston, a syndicate headed by Captain John G Crowley. Launched in 1903, it was the first seven masted schooner and the largest American sailing vessel ever built, and was only 37ft shorter than the German ship, the Preussen, which was known as the Queens of the Seas. Both sailing ships were made of steel and had steam engines to do the heavy work such as powering the winches and hoisting the anchors, the Thomas W Lawson however, had only 16 crew compared to the Preussen’s 46. The Thomas W Lawson was 408 ft long, 50ft wide and had a full spread of canvas of 43,000 sq ft. According to the ‘Western Daily Press’ of 16th December 1907 the ship was fitted with “a munificence” that would “startle the average sailor”. There were baths aboard for its officers with a hot and cold water supply, and the mess room fittings were more in keeping with a yacht than a sailing ship.

The ‘Jersey Evening Post’ of 12th February 1903 mentions that Captain Crowley was understood to have been mainly responsible for the design, having gone on many voyages with his father, who was a sea captain, and becoming master of his own vessel at a very young age.

The ‘Belfast Northern Star’ commented, on 21st February 1903, that the schooner was performing very well in the American coasting trade, and that on a recent trip from Boston to Norfolk it made an average of ten miles an hour with a cargo of 8000 tons of coal. However, it eventually proved to be uneconomical as a collier and was converted into an oil tanker.

The Thomas W Lawson, under charter to the Anglo-American Oil Company, was on passage from the Marcus Hook Refinery, Philadelphia to London. Two days before departure the new captain, George Washington Dow, had had to hire six new crew members to replace six seamen who had jumped ship due to problems with payment. The ship and its crew had a rough voyage, with the weather turning foul the day after its departure from the Delaware River. It lost most of its sails, all but one lifeboat and its Number 6 hatch was breached, causing the ship’s pumps to clog with a mixture of seawater and engine coal which was in the hold. Approaching the Scillies in poor visibility it mistakenly passed inside the Bishop Rock Lighthouse and, being in a dangerous position, let go its bow anchors, between the Nundeep Shallows and Gunners Rock, with the intention of weathering the approaching storm.

At 4pm on 13th December Bishop Rock Light fired a distress signal to call out the lifeboat, the wind being WSW Force 9 with rain. The ‘Morning Leader’ of 16th December tells how a boat, which had been attempting to relieve Round Island Light, and was returning to St Agnes, turned to establish the cause of the signals and discovered the schooner in a dangerous position amongst the reefs between Bishops Light and Annet Island. Huge seas were running in, under the gale from the west, causing the ship to strain dangerously at its cables. The relief boat could not assist but when the St Mary’s and St Agnes’ lifeboats approached the Thomas W Lawson, its captain assured them that it was in no danger and that he would be able to ride out the storm. The St Mary’s lifeboat had ventured so close to the schooner that a huge sea hurled them together causing the lifeboat’s mast to snap and, only with its own safety compromised, did its exhausted crew return to harbour. When a member of the St Agnes lifeboat crew fell unconscious and was not able to be revived, that lifeboat too was forced to return to shore, pleading with the schooner’s crew to accompany them. The captain, however, decided that they would remain on board but asked for an eye to be kept on their riding lights. The lifeboat managed to get a pilot, William Hicks, on board, where he remained with the anchored vessel.

The storm worsened during the night, and at 1am on the 14th watchers in St Agnes saw the lights vanish as both anchor cables parted and the ship was left to the mercy of the seas. The captain advised the crew to climb the rigging, but the ship was driven ashore at Minmanueth Rocks by tremendously heavy seas, its masts were lost and it capsized, killing most of the crew. Those that survived the fall from the rigging, despite wearing lifebelts, drowned in the thick layer of oil and the crashing rollers. A later telegram from the Lloyd’s agent reported that the vessel could now be seen bottom up and that three dead bodies had been found on Annet Island. One seaman, George Allen, also found on Annet, had survived but died within 24 hours of being rescued.

The master, Captain George Dow, and the engineer, George Rowe, were rescued from the Hellweather Rock and were the only survivors from the total of 18 crew plus pilot. George Rowe was unhurt and able to swim to a rope thrown from the rescue boat, the six-oared gig, Slippen, but the captain, who was a heavy man, had a broken wrist and could not swim out. Fred Cook Hicks, the son of the pilot who had died on the wrecked schooner, in what was described as a most daring and brave act, jumped into the tide race amongst a maze of rocks, with a rope around him, and managed to get the captain safely into the boat.

‘Lloyd’s List’ of 26th December 1907 reports that Mr T Algernon Dorrien Smith wrote from Tresco Abbey on the Scillies as follows: “We have formed a committee on these islands for the relief of the widow and family of W T Hicks, pilot and lifeboatman, who lost his life in the execution of his duty, at the wreck of the American seven masted sailing ship, the Thomas W Lawson. He leaves a widow and family of nine. It and the four youngest, aged 16, 15, 12 and 7, were dependent on his earnings for their support. Contributions will be gratefully received by me, or by Barclay and Co, bankers (Scilly branch).”

One article states that gold medals were awarded to the crew of the gig that rescued the two officers who had been washed on to the Hellweather rock, however the Lifeboat Magazine states that a Silver medal was voted to Fredk. Charles Hicks, who by swimming saved, at imminent risk to his own life, the captain of the schooner. The RNLI also voted a sum of 12 (assumed to be GBP, but the source is unclear on this) to the men who manned the shore-boat by means of which the rescue was effected.

A sum of 200 (again, possibly GPB) was voted by the RNLI, with an expression of deep sympathy, to the fund raised for the dependent relatives of W T Hicks, a lifeboatman, who lost his life on board the seven masted schooner, the Thomas W Lawson of Boston, wrecked at the Scilly Islands, 13th -14th December 1907.

In 2008 a memorial seat was blessed by the Reverend Guy Scott in the churchyard of St Agnes, the nearest inhabitable island to the wreck and the home of the pilot, Billy “Cook” Hicks. The seat, made of granite from a St Breward quarry, faces the mass, unmarked grave of many of Thomas W. Lawson’s dead.