During a weekend wander round the graveyard of St Michaels and All Angels Church in Bude, looking for gravestones of shipwrecked sailors, an unusual name caught the eye of Julie Satchell, our Head of Research. ‘Barnabas Stanlake Shazell’ drowned at Saunton in April 1899, with his body being recovered in June of that year. It was assumed the body was recovered in Bude, however, following up in the newspaper archive it became clear that Barnabas had indeed been a shipwrecked sailor and from a Bude ship – the ketch Joseph and Thomas – the loss of which would have considerable impact, not only to a local family, but for coastguard cover on the North Devon coast. Quite a tale soon began to unravel……..

Gravestone of Barnabas Stanlake Shazell at St Michaels and All Angels Church, Bude.

The Joseph and Thomas

The Joseph and Thomas was built in 1834, most likely in or around Plymouth. It was a two-masted ketch, 66 feet (20 metres) in length, registered as 47.58 tons and sailing with a crew of three. The archives of the Royal Cornwall Gazette show that at least between 1838 and 1858 the Joseph and Thomas was sailing a regular route, under Captain Kimbrell, between Plymouth, Charlestown and Mevagissey, with occasional trips to Par and Pentewan.

Details of when Bude became the ships home port have not yet been found, but we know that when here, Barnabas Shazell was the owner and Captain. He purchased the ship having previously owned a part share in the well-known Bude ketch the Ceres. Barnabas had served on Ceres as apprentice

Ketches of a similar type to Joseph and Thomas on Bude Canal (From the collection of the late Ray Boyd, reproduced with permission)

Coastal trading ketches plied the waters around the south west carrying a wide range of cargoes at a time when transport by sea was far quicker than any land routes. Bude at this time was well connected with ports across the County, to Bristol, South Wales and Ireland. In such a long service it is not surprising that the Joseph and Thomas encountered dangerous situations and had to have ongoing repairs. In 1889 the ship was practically rebuilt at a cost of £600 (around £49,000 at todays value). The reason for the rebuild must have been damage from when it was driven onshore on Coach Rock. On the 21st December 1888, around day break, they were trying to enter Bude Harbour with a cargo of slate from Port Gavern, when they were struck by a heavy sea. The crew climbed into the rigging and were rescued by the lifeboat Elizabeth Moore Garden. A display in The Castle Heritage Centre includes more details and the full RNLI transcript of the rescue. It was reported that “The ketch is much damaged, and it seems almost doubtful in her shattered condition if she will be got away again. Her cargo is being discharged” (Royal Cornwall Gazette).

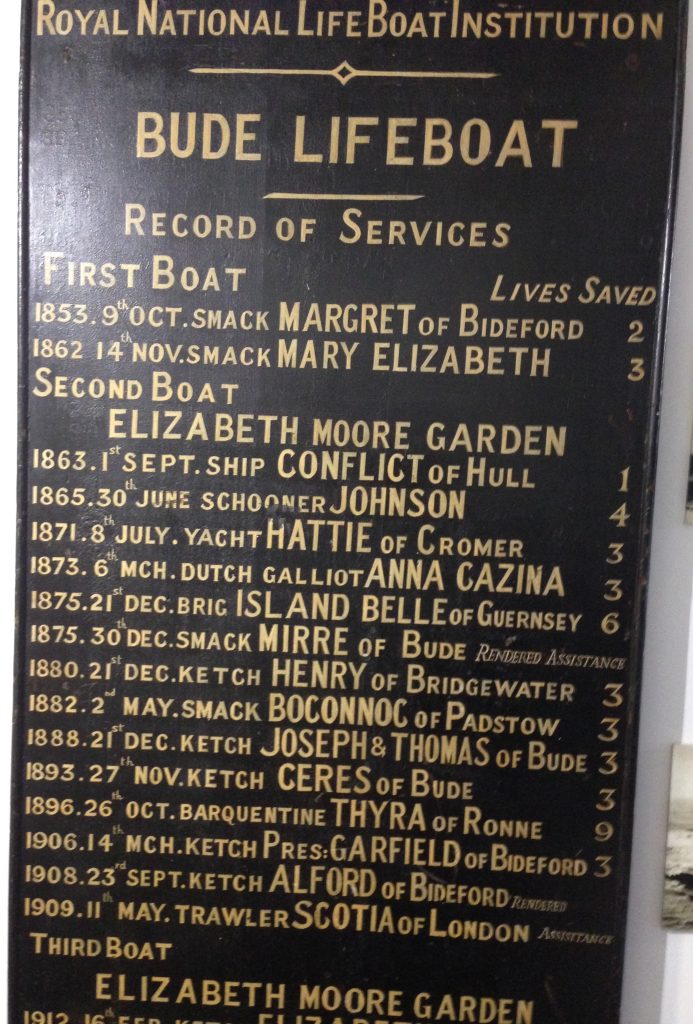

Bude Lifeboat board including the rescue of the crew of the Joseph and Thomas, part of the shipwreck display section at The Castle Museum, Bude.

A brief look at some of the voyages of the substantially rebuilt Joseph and Thomas in 1898-99 sees the ship in ports – Padstow, Cork, Penryn, Saundersfoot, Cardiff, Gloucester, Fishguard, Kinsale, Dublin, Newport, Swansea and Port Talbot. Many of the Welsh port trips would have been bringing coal back to Bude with the trip being possible to sail in a day with fair weather. Another voyage took a cargo of 85 tons of bricks from Gloucester to Cork – not all trips were to and from Bude.

The Wrecking and Repercussions

There is an unusual amount of detail available on the wrecking of the Joseph and Thomas due to an inquest and subsequent Board of Trade enquiry. The storm that was to take the ship was severe, newspapers around the country reported the casualties for shipping. It was a north westerly gale that ‘raged in the English Channel and along the South Coast’. The Joseph and Thomas had left Port Talbot on Monday the 3rd April with 88 tons of coal, heading for Penryn, all went well until Wednesday the 5th when the ship was ‘knocked about a good deal’, by the afternoon of the 6th they were taking in water. The seas they encountered must have been formidable with the sea in the Bristol Chanel reported to be ‘tremendous’, by the Friday the ship was in a dangerous situation.

Captain Shazell (recorded as being a splendid seaman) decided to head for Ilfracombe. Everything had been battened down to approach land and the ship was seen 7 or 8 miles offshore around 11.30am to the north of Baggy Point, but at around 13.30 it was driven in over Bideford Bar. The ‘doomed vessel’ was reportedly watched over ‘with great anxiety’ from the shore by a large number of visitors. It is hard to imagine how terrifying it must have been on the ship, almost all the sails had been lost, leaving the crew little they could do to help their predicament. They didn’t manage to launch any distress signals, their flags having been locked away in the battened down cabin. “They had eaten nothing since Wednesday morning, and were drenched, the waves coming clean over them. Captain Shazell managed to get into the rigging, Couch held on to the rudder, while Fred Davis, the third hand was amidsips”. Davis was either washed over board or had decided to try to swim for the shore, reportedly being seen in the water for 20 minutes before he was lost. Two very heavy seas capsized the ship on the sands with Shazell in the rigging. “Just afterwards Captain Shazell shouted ‘Good-bye, John! It is all up with us. God save me!’ and immediately Couch was washed overboard. He had secured a lifebuoy, and was cast ashore by the breakers. Fortunately, a number of persons had followed the vessel, and Couch, almost dead, was transferred to the hotel and well cared for” (North Devon Journal 13th April 1899). Other accounts add more detail: while most onlookers stayed on the cliff, a local builder, John Issac, headed towards the lighthouse and around 2pm he saw Crouch in the water – he went in and dragged him to the beach where he was taken behind the sandhills and a man sent to get blankets and brandy. Around 2.30 he was put on the coastguard rocket apparatus cart and taken to the hotel. Despite Couch being close to death and hardly able to speak when recovered from the water on Friday afternoon, as soon as the Saturday the bereaved Mrs Shazell had travelled from Bude to hear from him about the wrecking, an ‘interview’ that caused him ‘great distress’.

Some reports say that the coastguard used the rocket line to help rescue Crouch, however, others detail that the ship had been too far out to reach with the apparatus. Other articles question why the lifeboats had not been summoned, particularly due to the amount of time the ship was watched from the shore and known to have been stuck on the bar. This issue was examined in detail by the Coroner who heard evidence from Captain Heddon, the Lloyds Agent at Croyde, who indicated that the lifeboats stationed to the south west should have been wired by the coastguard. The jury of the inquest decided on the verdict “Accidentally drowned” adding that “If, when the vessel was in distress off Baggy and the adjoining coast, communication had been instantly made with the neighbouring lifeboats, the lives of the crew might possibly have been saved”. It was due to this rider that a Board of Trade enquiry was held on the 23rd May at Barnstaple. The enquiry considered issues related to the situation of the RNLI stations, their communications and the wrecking of the Joseph and Thomas.

The fact that there were lifeboats at Woollacombe, Saunton, Appledore and Clovelly, but none had gone to assist was examined in detail. The Lifeboat Institution at the time didn’t have look-outs on the coast but offered a reward of 7s for anyone reporting a vessel in trouble. The account of John Graves, the Croyde Coastguard, adds further detail of the events: he believed the ship was going ashore on Croyde Sands and got out the rocket brigade and apparatus as quickly as possible, he tried to telephone Ilfracombe but left before there was a reply and didn’t communicate with Saunton or Croyde lifeboat stations and in his rush to get on site with the equipment he left the station unattended. Only when he got to the shore did he see the wreck was drifting towards Saunton and out of reach.

The Enquiry considered whether the Croyde coastguard houses, being situated nearly a mile from the look-out which had no telephone caused a delay, and whether having only one man on duty at the watch-house had impacted the rescue. It was stated the issue was not with the individuals involved in the lifeboats, of which ‘they could not have anything better’, but the focus was on the communication systems and staffing levels. If the lifeboats had been called they would have launched. It took about an hour to launch the Saunton lifeboat as it needed 10 or 12 horses to do this, with around two hours passing between the Joseph and Thomas being seen in distress and the time of capsizing, it is possible the lifeboat could have reached them. As a result of the enquiry it was concluded that the coastguard station system could be improved due to the distance between them and that having only one person with responsibility in an emergency was too great. Another suggestion was that ‘blankets and stimulants’ should be stored close to the beach to be prepared for similar emergencies in the future.

It wasn’t for another three weeks after the enquiry, on the evening of the 13th June 1899, that the body of Barnabas was discovered. Mr J.H. Dean had been prawning at Westward Ho! when he made what must have been a gruesome discovery under the cliffs, close to Rock’s Nose. At 3am the following morning the coastguard and local police officer were able to reach the body, which was taken to Northam Mortuary. Suspecting the identity of the body, Barnabas’ brother in laws – Mr W. W. Petherick (merchant) and Captain R.W. Petherick – were sent for to confirm this. Reports include detail of his clothes and possessions; a dark blue jersey, dark trousers, lace-up boots, a pocket watch and chain, his purse (containing 13s in gold and silver) and a small knife. “Commanding the vessel during Captain Shazell’s illness on the voyage before the last ill-fated one, Mr. R. W. Petherick wore some of the same clothes, so that there can be no doubt as to the identity of the body”. Clearly a tragedy for this family that worked so closely together. Captain Shazell was 56 years old and left his wife and two grown up daughters. He had 40 years experience at sea in this area and on this type of ship. His body was conveyed to Bude in an oak coffin by hearse, and after a funeral was ‘laid to rest in a moss grave, the spot overlooking the harbour and home he loved so well’.

So, what of the remains of the ship? Reports say that large quantities of wreckage, including boxes of soap, tallow, and the hatches of a vessel, were washed ashore at Morte Bay. The main part of the ship ‘drifted away’ on the Saturday driven ashore on the Westward Ho! Pebbleridge. At the time of loss the ship was insured for £300 (around £23,500 today).

Finally, there are a number of shipwrecked sailors graves at St Michaels and All Angels Church, many have examples of maritime iconography included on them – a fascinating visit for those interested in the maritime history of Bude.