Women in maritime history, as with many other areas of our past, are often overlooked or forgotten. This doesn’t mean that they had nothing to contribute; just that these things were either barely recorded or simply lost to time. Uncovering these stories is vital in understanding our past. There have always been women in areas traditionally considered “masculine”. Below are the stories of just three such women, researched and written by volunteer and author Daisy Plant.

Ethel Langton

In March of 1926, when she was just fifteen years old, Ethel Langton found herself left home alone with her dog Badger for three days and three nights. What made this especially remarkable was that she lived in St. Helen’s Fort, located in the Solent. Her father was the lighthouse keeper there and, after a break in a storm, went ashore with his wife to fetch supplies to bring back.

Unfortunately, the storm returned while Ethel’s parents were away, and it was too dangerous for them to make the return journey.

In their absence, Ethel kept the lighthouse going by herself. In order to keep the light on, she would have needed to wind up the clockwork apparatus every four hours- all through the night, for three days, in a constant storm.

She later said that spent her time “playing Patience, reading, and preparing meals”. She was found by three fishermen, with only half a loaf of bread and a piece of cake left to sustain her.

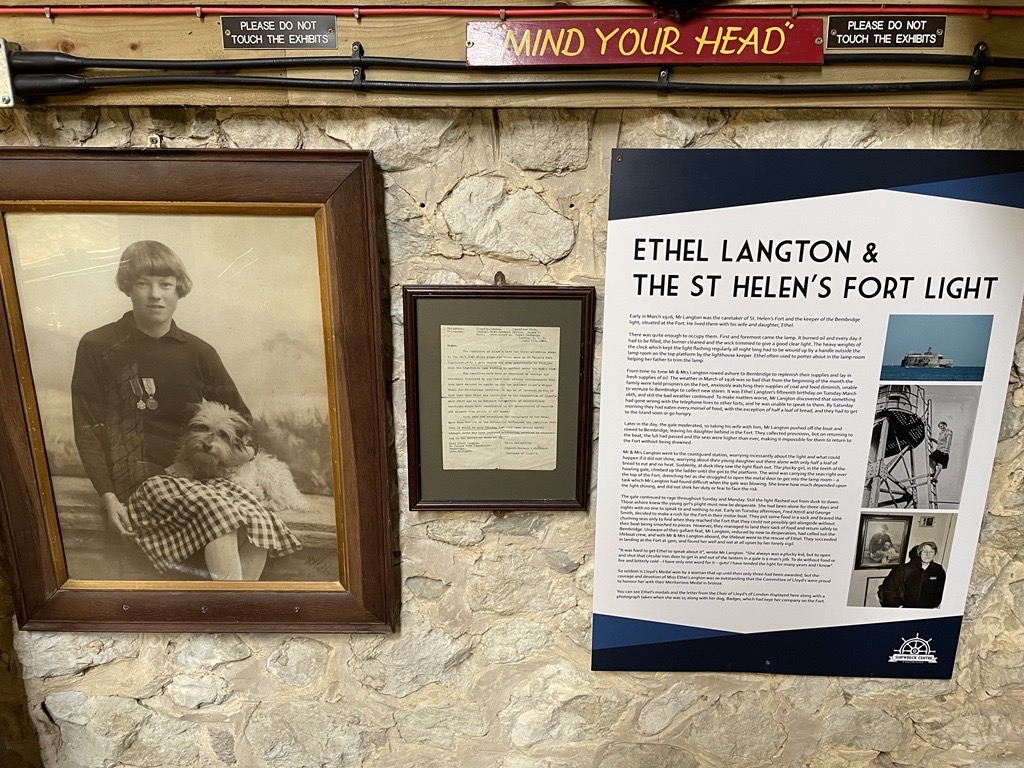

Ethel was awarded the Lloyd’s bronze medal for her bravery, which is on display at the Shipwreck Centre and Maritime Museum in the Isle of Wight. She was the first woman to receive this honour.

The Westminster Gazette also reported that she was flooded with letters and gifts- both from home and abroad- sent by fans.

Figure 1: A picture of Ethel with her faithful dog, Badger. A letter Ethel received for her bravery is also visible. Both items are on display at the Shipwreck Centre.

Figure 2: The Lloyds bronze medal Ethel received, on display the Shipwreck Centre.

Ella Trout

Ella Trout was a fisherwoman from Hallsands, Devon. She and her sister Patience dropped out of school when their father fell sick in order to operate his fishing boat, as it was their family’s only source of income. He passed away in 1910, when the girls were fourteen and fifteen years old.

In 1917, during the First World War, Ella was out fishing with her cousin (William, aged ten) when they witnessed an explosion. A ship, the Newholm, had been torpedoed just off Start Point by a submarine.

The pair raced towards it. As the wind was blowing in the wrong direction for them to use their sail, they had to row.

They were able to rescue one of the crewmembers. He was a fireman onboard the vessel, and he explained what had happened. As Ella and William were helping him, a motorboat arrived to aid in the rescue.

Twenty crew-members were unable to be saved.

For her role in the rescue, Ella received an OBE.

Blanche Coules Thornycroft

Blanche’s father, John Isaac Thornycroft, was a naval architect and engineer. He was the founder of the Thornycroft shipping company, and received a knighthood for his work.

Blanche was something of an unofficial apprentice. She seems to have been trained in her father’s craft in a way expected of an apprentice, but was never referred to as such during her lifetime. Indeed she seems to have actually tried to downplay her own role in a lot of the work the company did- although her own notes and letters betray just how involved she was. Her family also often spoke of her mathematical prowess.

The family home in Bembridge, Isle of Wight, had a specially built testing tank for model ships. This was disguised as a decorative water feature, and nicknamed “The Lilypond”. Ship models were towed at a controlled velocity, with equipment housed nearby to measure their results. A larger testing facility was later built at Steyne Wood Battery. The experiments conducted and recorded in both of these places were key to the development of several ship designs, most notably for the Royal Navy. She continued to work after her father’s death in 1928, when the company was taken over by her brother.

In 1917, Blanche was one of the first three women to be made an associate of the Royal Institution of Naval Architects.

Daisy is an author who has written a book ‘A History of Women’s Lives on the Isle of Wight’. Telling the stories of remarkable women, who were not queens or courtesans, but have incredible stories to tell.