The 1944 invasion of Europe was the largest amphibious assault ever undertaken in history. It required meticulous preparation in advance of D-Day, and significant logistical support in the following months.

The Solent was at the heart of this activity. Its sheltered waters were used to moor the bulk of the massive invasion flotilla, its low beaches provided ideal locations to build embarkation hards and its docks and quiet waterways provided ample space to build key components of the famed Mulberry Harbour.

The Solent 70 project has been exploring the role of the Solent in the build-up, execution and follow-up of this momentous event, in particular the role of purpose-built embarkation points, the construction of sections of Mulberry Harbour and the use of the underwater fuel pipeline PLUTO.

Thanks to the kind support of Hampshire County Council through their Hampshire Commemorates grant scheme and the New Forest National Park Authority through the New Forest Remembers: Untold Stories of World War II project, volunteers have been able to further research these elements of the Solent’s history.

Research has been conducted at the National Archives in Kew, London, Hampshire Records Office in Winchester, Portsmouth Records Office and Southampton Archives. By researching a number of historic documents, most of which were once classified at the highest level of secrecy, volunteers have been able to identify numerous maps, memos and photographs that have revealed previously unrecorded Second World War heritage.

Find out more about each element of the project:

To land thousands of men on an enemy held beach would not only require thousands of vessels to transport them; it would also require sufficient facilities in Britain to load and launch vessels from. The major ports along the south coast were all used to load large troop transports, supply vessels and of course the warships of the supporting naval forces.

But the ports would not be sufficient to load men and equipment onto all of the available vessels. Bottlenecks would develop around all of the ports if all the men, vehicles and supplies were routed through them. Fortunately there were alternatives available along the length of the south coast.

When Winston Churchill ordered the creation of a Commando force to “develop a reign of terror down the enemy coast”, he set in train initiatives and ideas that would see much of the infrastructure required for D-Day in place before an operations team for the invasion had even been created. Combined Operations was formed in July 1940, initially under the command of First World War Naval hero Admiral Roger Keyes, and from 1941 under the famed Lord Louis Mountbatten.

Construction

In May 1942, Mountbatten ordered the construction of 11 purpose built hards to serve landing craft and ships that would support his Commando operations on the European coast. These 11 were all constructed in the Portsmouth Command area (between Portland and Newhaven) and complete by July. These included six hards in the Solent:

4 hards at Stokes Bay Gosport (G1 – G4 Hards).

1 hard at Lymington (A Hard)

1 hard at Lepe (Q Hard)

The first use that some of these hards would see was in the Dieppe Raid of August 1942. Meanwhile, the first phase was expanded with a second in June, and a third in early 1943 that eventually saw a further 57 hards built along the south coast and in the Thames Estuary, as well as a further 12 projected hards in Wales and 8 in Scotland. In the Solent this added:

4 hards at Southampton (S1 – S4 Hards)

1 hard at Stanswood Bay (Q2 Hard)

2 hards in Portsmouth Harbour, Gosport (G5, GH and GF).

The vast majority were complete by spring 1943, although three – including G5 at Gosport – were abandoned, bringing the total number of hards available on the south coast to 65 by summer 1943.

The construction of the hards was shared between the Admiralty and the War Office. The War Office dealt with land requirements, including link roads built to connect the hards to the public highways, whilst the Admiralty were responsible for the construction of the hards themselves. That said, all of the work was actually delegated to civilian contractors hired by the military.

The hards were built specifically to serve two types of assault vessel; Landing Craft Tank (LCTs) or Landing Ship Tank (LST). In purpose, these vessels were the same; designed to land tanks and other vehicles directly onto a beach. LSTs were significantly larger and had bow doors, whilst LCTs had a single bow ramp. In addition a variety of other flat bottomed vessels (such as the smaller Landing Craft Infantry or Landing Ship Infantry) could be accommodated on the hards. Most of the beach hards in the Solent were ‘all-tide’ in that they could be used at all times of the tide, although the nature of landing craft meant that a vessel beaching at high tide would remain beached during low tide and would have to wait for the next high tide to refloat again.

Design and Facilities

The hards very simple structures; little more than slipways into the water that the landing craft could beach on. Some made use of existing slipways, but were suitably reinforced for military purposes. In the Solent, the Lepe, Stanswood Bay and Stokes Bat hards were all built on sand and shingle beaches. To create a tough all weather apron that would not erode or shift like a soft beach and that heavy vehicles could drive onto to reach the vessels, concrete was laid above the high water mark and in the intertidal zone beach hardening mats were used to create a solid surface. A number of designs for beach hardening mats were submitted to the Directorate of Fortifications and Works; the final version was of a reinforced concrete design, using steel rods to strengthen blocks approximately 70cm by 40cm and 15cm thick. The rods were also used to interlink with the neighbouring block, creating a continuous and well secured surface. The blocks were given a griddle pattern on the surface for improved grip, which has led to their common name of ‘chocolate blocks’.

Just offshore of the ramps, mooring dolphins were built in the water. As well as securing the vessels, the dolphins were used to support ramps allowing men to embark onto the upper decks of the landing craft. Onshore, accommodation was provided for the hard crew. In the early hards, this consisted of an officer and 11 men; later hards show evidence of several dozen men and some members of the Woman’s Royal Naval Service (WRNS or Wrens). Living quarters, piped water and electricity were all provided, as were latrines, which were considered very important when Wrens were present!

To service vessels beached on the hards, workshops and operational beachmaster offices were built. Refuelling facilities were also established at every hard, as it was felt desirable to be able to refuel the landing craft at the same time as loading, thus saving time before they undertook operations.

Trials at Lymington in October 1943 showed several problems in carrying out night operations using oil lamps. A new system of electric lighting was trialled at Stokes Bay in November and electric lighting was eventually adopted at all the hards.

D-Day

The Solent hards were in regular use throughout 1942 and 1943 for training exercises and other operations. In the build up to D-Day they were in near continuous use; the loading table for Q2 Hard at Stanswood Bay shows that the moment a ship departed its mooring, another took its place. The hards at Lymington and Lepe were mainly used to embark troops bound for Gold Beach, whilst the Southampton hards were used by Canadain forces bound for Juno Beach. Gosport was used by a mix of troops bound for Juno and some for Sword Beach. Many men and vehicles embarked several days before D-Day and remained at moorings in the Solent until they set sail for France.

Operation Turco

D-Day did not mark the end of the hards’ role in Operation Overlord. A thorough plan had been drawn up for the resupply of the Normandy beachhead and the Solent would be key to that operation.

The Solent’s role in reinforcing the beached cannot be underestimated. Between 7 June and 31 July 1944, 650,519 men and 137,249 vehicles made their way to France on ships, landing craft and landing ships that sailed from Southampton, Portsmouth and the hards (this is in addition to the 73,114 men and 9,188 vehicles that left the Solent to take part in the initial assault). In the same period, 34,222 prisoners and 53,423 wounded soldiers came back to the UK through the Solent ports and hards.

“If you have faith the size of a mustard seed, you could say to this mulberry tree, ‘Be uprooted and planted in the sea,’ and it would obey you!” (Luke 17:6)

Mulberry Harbour was perhaps the single greatest innovation that ensured victory for the Allies in the Battle of Normandy that followed D-Day. Without port facilities, the Allies would never have been able to build up their forces in France sufficiently to be able to withstand the German’s efforts to defeat them.

Allied planners realised at an early stage that they would need a port facility very soon after arriving in France. Without one, all the men and materiel that would be needed to secure the beachhead, would have to be landed directly onto the captured beaches. This would necessitate using landing craft, which were relatively small and inefficient next to the facilities that a deep water port can offer.

However, a port would be hard to capture quickly, and there would be no guarantee that the German forces would not destroy the port before they abandoned it (indeed, most of the ports they abandoned were thoroughly wrecked by the time the Allies reached them).

The solution, in the eyes of Winston Churchill and several senior planners, was to take a port with them. A floating harbour that could be transported directly to France, and assembled off the beaches would ensure that sufficient facilities were in place to land large quantities of heavy equipment to supply the British, Canadian and American armies.

The plan called for two Mulberry harbours to be constructed at Normandy; Mulberry A at the American beach of Omaha and Mulberry B at Arromanches on the British Gold beach. With the beaches successfully captured, elements of Mulberry were towed to France as early as 6 June. Assembly began immeadiately and both harbours were operational within ten days, although amendments and expansions continued well into July.

Unfortunately a large storm struck the beaches on 18th and 19th of June. Mulberry A was almost totally destroyed and Mulberry B was not much better. The decision was made to abandon the American harbour and all the surviving elements were incorporated into Mulberry B. It was succesully reopened and renamed Port Winston. By October when it was officially closed, over 39,000 vehicles and 220,000 men were landed at the port.

The Construction

Facilities all along the south coast were used to construct the various elements. London docks and some ports around the coast were used for building large elements of the harbours, but it was the Solent that sat at the centre of the construction.

At Southampton Docks, Phoenix Caissons, the large concrete blocks that could be floated to Normandy and then sunk to create a breakwater, were built in the dry docks of the old port. Photos discovered in Southampton City Archive also showed bombardons, large floating breakwaters, also being constructed ion the King George V dry dock. Records in the National Archives showed that these were tested in Portland Harbour when complete, and they were despatched from there to France in the days following D-Day.

Across the water at Marchwood, a new military port was built largely to serve the forces for the invasion, and to construct pier elements. ‘Whale’ roadways were built here; these had been extremely well designed so that they would be able to flex with the currents that they would be exposed to. These roadways would float above the water on ‘Beetles’, hollow concrete floats that could be anchored to the sea bed. When put together, these floating roadways could stretch one mile out to sea, into deeper water where larger ships could berth at the pier heads.

Further round the coast, Beetles were also built on the River Beaulieu. An old Oyster Bed at Cobb Creek was dredged and became a Beetle construction site.

The largest Solent construction sites were at Lepe and Stokes Bay. Here they built Phoenix Caissons on the beach so that they could be directly launched into the sea. Six were built at Lepe and fourteen at Stokes Bay. All were built concurrently in separate spaces along the beach.

Legacy

Some legacy of this construction survives in the Solent today. In the 1950s, when the marshland at Dibden Bay was reclaimed, several dozen Beetles were used to create breakwaters behind which the land could be filled. Lines of these beetles still survive on the foreshore today, and at low tide thety can be seen from the Red funnel ferries or from Town Quay, lined up along the beach across Southampton Water. It’s doubtful that these Beetles ever went to Normandy; most likely they were spares from Beaulieu or Marchwood that had been kept in reserve in Southampton Water.

During the latter stages of the war, when other ports had been captured and Mulberry was no longer required, large numbers of Whale roadway sections were reused to repair bridges in France. A great many pieces of Whale roadway are still to be found on some of France’s quieter roads even today. In Southampton, two sections were used by Red Funnel as boarding ramps for their old ferries. One section is still there today. Although it is no longer used as a boarding ramp for the newer ferries, it remains in impressive (if untidy) condition. Mulberry was only expected to last six months as a port; the fact that elements such as these survive in such good condition shows the true quality of their construction.

During the latter stages of the war, when other ports had been captured and Mulberry was no longer required, large numbers of Whale roadway sections were reused to repair bridges in France. A great many pieces of Whale roadway are still to be found on some of France’s quieter roads even today. In Southampton, two sections were used by Red Funnel as boarding ramps for their old ferries. One section is still there today. Although it is no longer used as a boarding ramp for the newer ferries, it remains in impressive (if untidy) condition. Mulberry was only expected to last six months as a port; the fact that elements such as these survive in such good condition shows the true quality of their construction.

In Langstone Harbour lie the remains of a large Phoenix Caisson that was abandoned here in 1944. This caisson developed a crack during construction and would not have survived the journey to France. Instead, it was towed to its present location and abandoned. Research at Hampshire Record Office in Winchester showed that in 1960, the caisson was sold by the Admiralty. Initially it was due to be sold to SB Lunzer & Co Ltd., a London based company and removed. However this prompted protests from local residents and the Admiralty, no doubt somewhat surprised by this response changed the sale conditions. Instead of requiring the caisson to be removed, they now stipulated that it must remain undisturbed. This wasn’t exactly a good deal for Lunzer (who it is believed, were originally interested in the scrap value of the reinforcing steel), and if their history was often blighted by such poor value purchases, it may help explain their subsequent liquidation. The caisson lies on land held under lease by Langstone Harbour Board and in the absence of any other owner, it is most probably considered to be their property today.

Two more phoenix caissons survive not far away in Portland Harbour. In 1946, ten Mulberry Harbour Phoenix Caissons, reputedly used at Normandy, were taken to Portland. They were used as a breakwater and to provide shelter for the construction of the new Castletown Pier (now Queens Pier) and it was originally intended that all ten would be retained permanently, to create an inner harbour that could be used for berthing large Royal Navy destroyers.

However, in May 1953 the British Admiralty placed the Phoenix Caissons at the disposal of the Dutch government for use in dyke repairs in the wake of a massive storm in February of that year. Shortly thereafter, eight were re-floated and towed to Zeeland province. By July, six were in Zeeland, and two more were ready to be towed over. One of the first six caissons is believed to have run aground and was later used at Serooskerke. Four were used to block a dyke on the 6th and 7th November 1953 at Ouwerkerk. One was used at Kruiningen on the Scheldt estuary and another two at Dreischor (Stevensluis). The four caissons at Ouwerkerk were designated protected monuments in 1965 (although this may have been 2003 ). In 2001 they were officially opened as a museum dedicated to the 1953 floods.

However, in May 1953 the British Admiralty placed the Phoenix Caissons at the disposal of the Dutch government for use in dyke repairs in the wake of a massive storm in February of that year. Shortly thereafter, eight were re-floated and towed to Zeeland province. By July, six were in Zeeland, and two more were ready to be towed over. One of the first six caissons is believed to have run aground and was later used at Serooskerke. Four were used to block a dyke on the 6th and 7th November 1953 at Ouwerkerk. One was used at Kruiningen on the Scheldt estuary and another two at Dreischor (Stevensluis). The four caissons at Ouwerkerk were designated protected monuments in 1965 (although this may have been 2003 ). In 2001 they were officially opened as a museum dedicated to the 1953 floods.

The two caissons that were left in Portland today provide shelter for ships moored on the west side of Queen’s Pier. They were designated as listed buildings in 1997.

PLUTO was an ambitious plan to supply fuel to Normandy using an underwater pipeline. Knowing that vast quantities of fuel would be required to supply vehicles in France, Allied planners decided to lay a pipeline along the seabed of the English Channel, from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg. It was hoped that by mid-August 1944, PLUTO could supply 1 million gallons of fuel a day.

PLUTO was an ambitious plan to supply fuel to Normandy using an underwater pipeline. Knowing that vast quantities of fuel would be required to supply vehicles in France, Allied planners decided to lay a pipeline along the seabed of the English Channel, from the Isle of Wight to Cherbourg. It was hoped that by mid-August 1944, PLUTO could supply 1 million gallons of fuel a day.

In the event, PLUTO was not ready until late September and only managed to supply 700,000 gallons before the pipeline failed. By then Allied land forces had advanced well beyond Normandy. The Isle of Wight pipeline was abandoned, but a new pipeline from Dungeness to Bolougne was more successful.

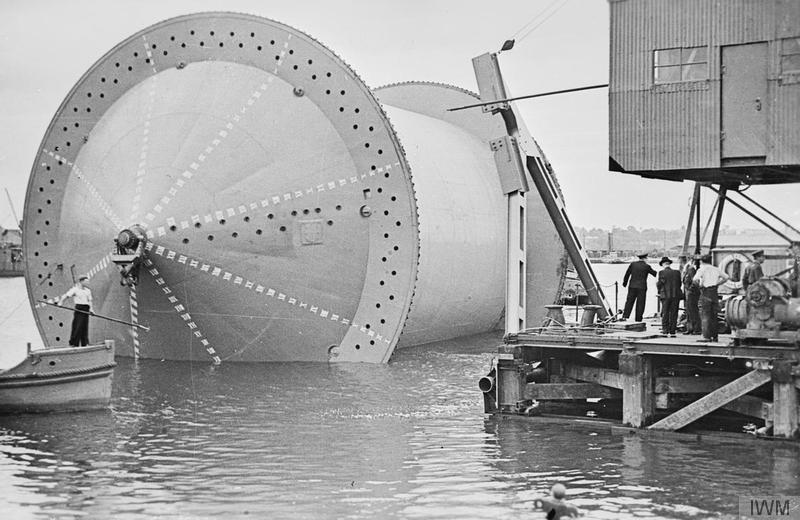

Fieldwork identified and recorded the remains of several sections of pipeline that had been laid between Lepe on the Hampshire coast, and Thorness Bay on the Isle of Wight. Several of these had been laid for training purposes and were recovered after the war. At the National Archives, previously unseen aerial photographs were discovered that appear to show the first trials of the ‘Conundrum’ pipe layer taking place off Hengistbury Head. The Conundrum, a huge ‘cotton reel’ that unwound the pipeline onto the seabed, was later used to lay the pipeline to France.

Fieldwork identified and recorded the remains of several sections of pipeline that had been laid between Lepe on the Hampshire coast, and Thorness Bay on the Isle of Wight. Several of these had been laid for training purposes and were recovered after the war. At the National Archives, previously unseen aerial photographs were discovered that appear to show the first trials of the ‘Conundrum’ pipe layer taking place off Hengistbury Head. The Conundrum, a huge ‘cotton reel’ that unwound the pipeline onto the seabed, was later used to lay the pipeline to France.

The genrous funding from Hampshire County Council through their Hampshire Commemorates grant scheme and the New Forest National Park Authority through the New Forest Remembers: Untold Stories of World War II project, enabled a travelling exhibition to be displayed in a variety of locations along the south coast of Hampshire. For those unable to see it at the time, the panels are reproduced below.