Vessel History

HMS Impregnable was a 2nd rate ship of the line. 2nd rates, typically carrying 90 to 98 guns, were developed in the late 17th century as a cheaper alternative to the larger 1st rates. They were still sufficiently large to serve as flagships, and took their place in a navy which utilised the smaller 3rd rate 74 gun ships as the backbone of the fleet.

HMS Impregnable was ordered in 1780 and was built at Deptford between 1781-1786, with a gun deck length of 177ft, breadth of 49ft and a depth of hold of 21ft. Impregnable‘s career was dominated by escort and transport duties, but it saw action on several occasions. The largest action the ship was involved in was the Glorious First of June (or the Third Battle of Ushant) in 1794, the first and largest fleet action between the Royal Navy and the French Atlantic Fleet during the French Revolutionary Wars. The ship was also involved in several other minor engagements with the French during the course of the wars.

In October 1799, Impregnable, under the command of Captain Faulknor, was escorting a convoy of ships from Lisbon to Britain. When the convoy reached St. Catherines Point, Faulknor signalled for the merchant ships to head for shore and Impregnable began the run in towards Portsmouth. Command was handed to the Master, Michael Jenkings, for this final leg of the journey. The wind from the south strengthened and the ship was soon travelling along at 10 knots. It was now 6pm on Friday 18th October 1799 and darkness was falling. Jenkings, aware that the Princessa Shoal lay ahead, ordered crewmen to the wheel and the leadsmen to the chains.

Faulknor warned that they were going too fast and suggested that Impregnable should spend the night in open water instead of trying to reach Portsmouth, but Jenkings was confident with the speed and the position of the ship. As darkness fell though, he was finally forced to acknowledge that they would have to anchor. All sails were ordered in and Impregnable swung round into the wind with its bow to the south east. The anchor went out, but only a third of the cable followed before the ship struck the seabed.

The anchor dragged and the stormy conditions prevented any attempts to stabalise the ship with a kedge anchor. The rudder was also soon beaten off. The masts were cut away, but the ship rode into shallower water and a distress cannon was fired. The storm mean that no ships from the dockyard could risk coming to there assistance. Initially it was hoped that the vessel could still be saved, but dawn of the Saturday morning found Impregnable lying with its bow to the north-north-east and taking on water. Jenkings now realised just how far off course they had become and vessels from the dockyard began salvaging the guns.

Sunday saw the guns, shot and powder removed, along with water barrels, provisions and anything else to lighten the ship’s load. By Monday morning however, the pumps could not keep up with the volume of water in the hull and soon more seawater poured into the ship. All the crew were taken off and shipwrights began to strip the vessel. The shipwrights were not the only ones stripping Impregnable though, prompting an official warning from the Navy, printed in the Hampshire Telegraph. On 6th November 1799 the ship was sold to a Portsmouth merchant who stripped what was left. Newspaper adverts for regular sales of parts of the wreck appeared until May 1800 when all of the accessible remains must have been salvaged.

Of the 19 Naval ships wrecked in 1799 the Impregnable was considered the biggest loss. As a result the navy was short of larger ships and decided to reverse the order for HMS Victory to be converted into a hospital ship. Impregnable’s loss secured Victory’s survival.

History of Investigations

The thorough stripping of Impregnable meant that anything that could be reached down to the lower hull was removed. Almost 200 years after slipping under the waves the wreck was rediscovered in 1981; an expedition lead by Rex Cowan and Richard Larn, involving local divers John Broomhead and Arthur Mack discovered the remains using a magnetometer. Later in the 1980s the site was rediscovered by the 308 Sub Aqua Association Club, who recovered a small number of objects from the site. From the late 1980s it is thought that the site was not dived frequently, although it is listed in the Dive Wight and Hampshire.

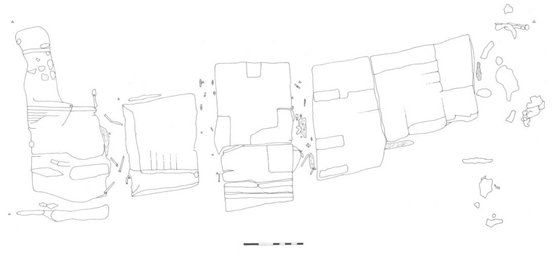

The Impregnable site was the focus of the initial Maritime Archaeology Trust Eastern Solent Marine Archaeology Project (SolMAP) in 2003 when a site plan was created. The wreck lies in around six metres of water and its main features are four large concreted mounds of iron ballast bars and lower hull remains. These have not been disturbed since the wrecking and represent an unusual opportunity to research the ballasting of Naval vessels. Copper bolts which once held the ship’s hull timbers together protrude from between the mounds of iron. A sketch produced by John Broomhead and made available for study by Arthur Mack, appears to show the site has not significantly changed since 1981; the mounds of concreted iron ballast are still prominent, but in 1981 there were many more copper pins in position along with more cannon balls covering the ballast mounds.

While initially looking relatively unassuming this site is revealing interesting information on late 18th century ballast and the types of archaeological material that can be preserved in this environment. A particularly interesting discovery was the extent to which an impression of the hull timbers, now degraded away, has been preserved by the iron concretions. This information should make it possible to study characteristics of the timbers even though they have long since disappeared.

The survey in 2003 included monitoring of seabed levels adjacent to the ballast blocks, recording of a feature identified through geophysical survey lying 12 metres to the south of the site (possibly part of the stern of the vessel), completion of section drawings of the upstanding remains, detailed investigation of the position of individual ballast bars and a timber assessment by dendrochronlogist Nigel Nayling.

Since then, the Trust has returned to the site to develop an understanding of the structure through enhanced survey to gain detail of the ballast bars within the mound and create section drawings. A small number of artefacts have been raised from the site to aid research.

The levels of seabed deposits around the site have been monitored on return visits since 2003, in order to assess any changes and their potential impacts. The remains are in a seabed which consists of shingle and trends demonstrate that seabed levels along the north east edge of the site are relatively constant with fluctuations in other areas. Some areas of the site are affected by the actions of burrowing crabs and lobsters which remove sediment from beneath the structure to create their homes. The exposed remains are relatively robust and there appears to be little overall change to the site since 2003.

In 2010 further monitoring was undertaken as part of the Eastern Solent Marine Archaeological Project, supported by the Archaeological Atlas of the 2 Seas project, and the site was also one of the subjects of the Heritage Partnership Agreements project, the report for which can be found here.