MAT team member Carley Divish talks about her work using photogrammetry, and how this 3D modelling technique can be used to bring sites and artefacts to life.

Working at the Maritime Archaeology Trust requires a variety of skills. Some of those can be taught, but some of them, like curiosity, are harder to come by. Thankfully, in my time at the MAT I have developed skills in photogrammetry, laser scanning, and processing those models well.

Photogrammetry is when you take a lot of photos of something, and an interactive 3d model can be made of it. You have to take photos from every side and every angle, making sure they overlap so that the computer can see how everything fits together. Laser scanning, also called structured light scanning, uses a special tool that has lasers taking photos of the object. It can be easier in ways than photogrammetry, because you can see immediately what pieces are missing and where you need to scan again, but you need the right scanner for the object size. I have never seen a site-wide laser scanner, so photogrammetry is the plan when we document sites.

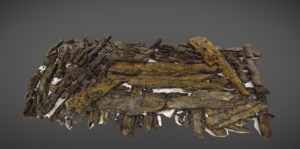

During my time, I have modelled anything from bronze placards from old vessels to wooden posts from the Bronze Age to entire sites underwater. Photogrammetry can be difficult with wooden artefacts because photos reflect light, so you need to get the artefact as dry as possible to remove reflection but keep it wet enough that it doesn’t dry out the wood and crack it. Metal artefacts aren’t much easier, however, because the metal reflects! Sometimes we spray the metal with a matte powder that rubs off but takes away the sheen. Laser scanning has the same issue, because lasers refract! All of that makes artefact photogrammetry a challenge, but a fun one. I get to figure out solutions to all of these problems on the fly. With photogrammetry, you have to turn an object upside down to take images of the bottom, then manually put the two models made from the upside-down photos and the right-side-up photos together. Sometimes that can be difficult too. Laser scanning has the benefit of matching those sides together for you! As long as the object is stable during a scan, you can flip it any which way then scan it again and the software figure the rest out for you.

When I do photogrammetry of an entire submerged site, that is where a lot of fun and extra challenge comes in. There is no object to turn around and upside down, so instead the focus is on hovering the same distance above the seabed, making sure the pictures are focused, and making sure the camera protection doesn’t leak. It is difficult in a different way, but honestly I find photogrammetry underwater much easier because stitching together an upside down object with its right side up model is a lot of work!

Even after the models are made, they are not done yet. We still need to colour correct, add backgrounds, add labels to important aspects, and make them more realistic. We have to go into image editing software and add texture back where we removed it, add shine back where it needs to be, and overall make the artefact look on the screen exactly like it does when you see it in person. That can take a lot of time and tiny adjustments. Then we can publish the models! We have all of our models on a website called Sketchfab, linked here, and you should go see the vast array of projects we have used this work with! Maritime Archaeology (@maritimearchaeologytrust) – Sketchfab

The hard part is only starting, however. After all that work taking the photos, colour correcting, processing, and shining up, we have to understand what the models mean. At the Trust, we think that photogrammetric models are really impressive, but do they matter if there is no reason to take them? We model sites that are changing, like Bouldnor Cliff, artefacts that will change (wooden ones), and anchors from the north sea that will never be seen again. These models document the fleeting nature of archaeology but also show change over time. When we at the Trust make models, all that effort needs to have meaning. We strive to work with the models and show them to people, to get meaning out of them, and to make them more than pixels on a screen. To make sure they matter to you, the people who support us.