For the Maritime Archaeology Trust’s Metal-Hulled Sailing Vessels project, generously funded by Historic England and Lloyd’s Register Foundation, volunteers are investigating the potential and significance of the collection of metal-hulled sailing vessels located within English territorial waters. However, every vessel needs ports, many needed tugs, and volunteer Roger Burns takes a look at a selection of ports worldwide and tugs associated with the project’s Metal-Hulled Sailing Vessels. Most of the images expand automatically when clicked.

Ports

Designated ports hold the registrations of all the project’s Sailing Vessels, and although some of the ships were “of a named port” prior to the Introduction of the Moorsom method by 1854, subsequently specific ports were used in the UK and abroad, often where the ship was owned.

Many ports, particularly where ship building featured, had dry docks used by Sailing Vessels to effect repairs when necessary. The project’s Sailing Vessels have visited nearly 450 ports worldwide; some were small, many large, with a mixture of coastal, estuarial and inland. Examples of inland ports are Limerick, some 40 miles from the mouth of the Shannon, and Calcutta, now Kolkata, on the Hooghly River some 80 miles from its mouth at the Bay of Bengal. Some ports, such as Ipswich about nine miles inland, required lighterage to offload some cargo before larger Sailing Vessels could dock. Morrison’s Haven, east of Musselburgh, was infilled in the 1920s and Redbridge Wharf, at the head of Southampton Water, is now a bird watching and children’s play area. The following selection of ports are neither specific for registration or repairs, but were frequently visited.

Glasgow

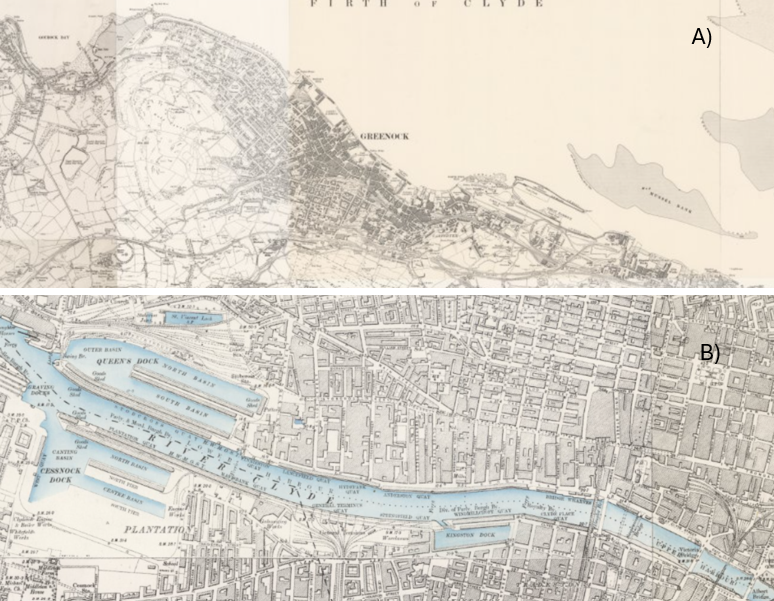

Dubbed as “The Second City of the Empire” in the late second half of the 19th century although Liverpool, Dublin and other places had similar claims. The River Clyde was the heartbeat and the city underwent massive expansion up to the First World War together with dredging and improving alignment of the river thus facilitating construction of larger ships but importantly accommodating larger cargo vessels enabling trade expansion. During this period, four large tidal basins and docks were constructed, named Kingston, Queen’s, Prince’s (also known as Cessnock), Rothesay (now infilled, opposite River Cart tributary) and Clydebank which was the original name of Rothesay Dock, Figure 1B. Additionally, quays were extended along both north and south banks as far as Partick and Govan. In the year to June 1914, over 10 million tons of cargo were handled by almost seven million tons of shipping. Infilled docks are now redeveloped. There was also Greenock Dock, Figure 1A, some 19 miles downstream of Queen’s Dock at the mouth of the river Clyde from where many of the project’s Sailing Vessels arrived and departed although some went upstream into Glasgow.

Figure 1: Glasgow Docks

Fig. 1A: Greenock. Fig.1B: Upstream of Figure 1A

Source: Georeferenced OS Six-Inch, Ireland, Scotland, England & Wales, 1888-1915. National Library of Scotland. CC-BY (NLS)

Liverpool

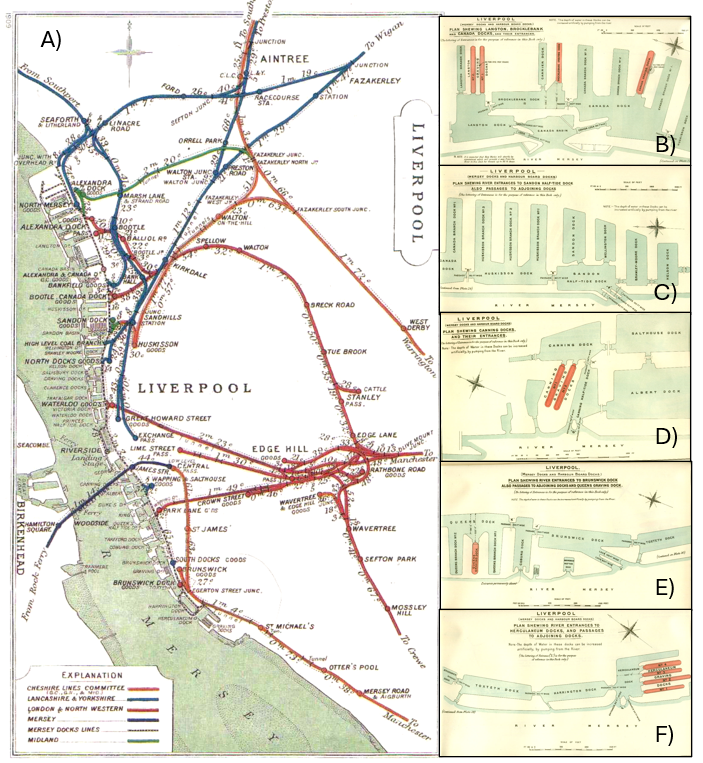

Birkenhead to Wallasey on the west side of the river Mersey had its own dock system, and this narrative refers to the east side of the river. Liverpool comprised up to 43 docks, of which 15 are now infilled with a further three reduced to inland canal boat depth; this array of docks comprised a 7.5 mile interconnected system which was the most advanced dock system in the world, enabling movements through the docks isolated from high tides in the Mersey. At its peak, the Mersey Docks and Harbour Company freight railway totalled 104 miles of track serving the docks and connecting with other lines, Figure 2A. Dock layouts are illustrated in Figures 2B to 2F.

Figure 2: Liverpool Docks 1909

Fig. 2A: Rail connections with the Liverpool Docks – Railways Clearing House, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig 2B: Liverpool – Langton, Brocklebank and Canada Docks. – British Admiralty, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2C: Liverpool – Sandon Half-Tide Dock with passages to adjoining Docks. – British Admiralty, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2D: Plan showing river entrances to Canning Dock – British Admiralty, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 2E: Plan showing river entrances to Brunswick Dock with passages to adjoining Docks – British Admiralty, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig 2F: Liverpool – Herculaneum Docks with passages to adjoining Docks – British Admiralty, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Always very busy, Liverpool port had and has extensive connections with the rest of the world, for passengers and freight, and was also home to several Shipping Lines. Three of the project’s Sailing Vessels were lost within the river Mersey, and a further four within 12 miles of it’s mouth.

London

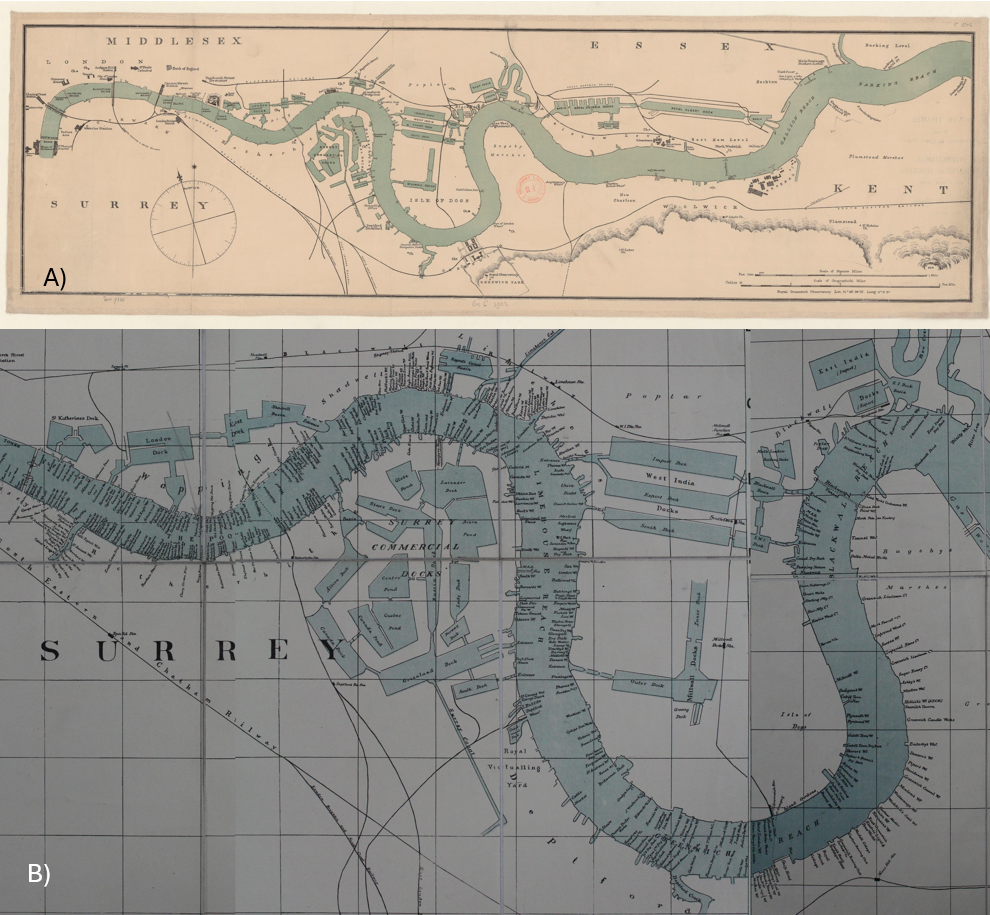

From the 12th century, marshland along the Thames began to be developed with embankments. Initially quays were developed, such as Figure 3B, and became known as the Pool of London which is the City of London or Southwark as known today. Space was becoming a problem, and in 1696 Rotherhithe’s Howland Dock was built, providing sheltered anchorage for up to 120 vessels, subsequently expanded becoming the Surrey Commercial Docks. Judged a success, this prompted creation of the following docks with opening dates; West India 1802, London & East India both 1805, Surrey 1807, Regent’s Canal Dock 1820, St Katharine 1828, West India South 1829 and mostly eastwards Royal Victoria 1855, Millwall 1868, Royal Albert 1880 and King George V Dock 1921, Figure 3A with expansion downstream of Tilbury. At one point, London was the world’s largest port including wet docks, dry docks and shipyards but in the 1960’s many progressively closed brought about by container shipping; cargo and passenger handling and general port facilities are now in the lower reaches at Tilbury, Purfleet, London Gateway, Canvey Island, Dartford, Northfleet, Greenwich, Silvertown, Barking, Dagenham and Erith. Greenwich was a regular arrival and departure point for the project’s cargo vessels. The docks’ history can be traced by visiting the Museum of London Docklands.

Figure 3: London Docks and Wharves

Fig. 3A: River Thames. From Westminster to Cross Ness 1895 – Bibliothèque nationale de France, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 3B: Thames wharf map 1905 Tower Bridge to Bow Creek – G. D. Evans, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

One of the project’s Sailing Vessels was lost east of Gravesend in the river Thames, and a further four in its lower reaches before the North Sea.

Newcastle N.S.W.

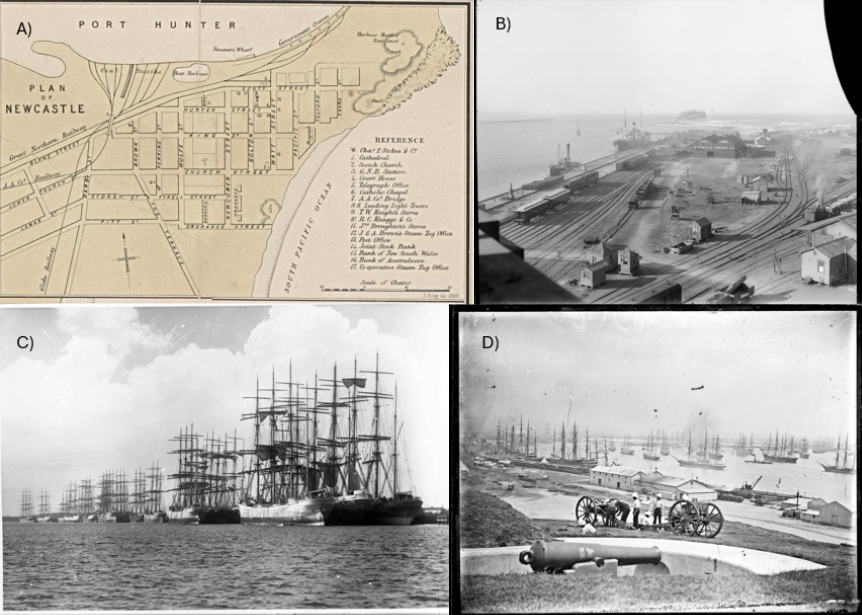

Now the world’s busiest coal export port, coal has long been exported from Newcastle, and several of the project’s Sailing Vessels are listed with incoming unidentified cargoes and with coal exports from Newcastle to many locations. Newcastle’s harbour, now named Port Hunter, dates back to the first recorded shipping movement in 1799 and was first dredged in 1859 transforming the mud flats and small channels over time to a large deepwater facility. An iron and steelworks was established in 1911 attracting further Government investment including rock blasting, and general reclamation for additional port facilities. This long period of port enhancement coupled with extensive commercial trading has created a legacy of heritage buildings and other objects which are now the subject of a Heritage and Conservation Register. It is estimated that to present in excess of 200 vessels have foundered entering or leaving the port and embracing a wide area inland up river and off shore. In Figures 4A and 4B, railway sidings to near dockside are evident, crucial for delivering coal and other goods. Figures 4C and 4D illustrate the large numbers of Sailing Vessels visiting the port.

Figure 4: Newcastle, New South Wales.

Fig. 4A: Plan of Newcastle, 1868. Part of a larger map – Allan, D. T., Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4B: Nobbys & entrance to harbour from Customs House, Newcastle NSW, 1906 – State Records NSW, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig 4C: Sailing ships at Stockton Wharves, Newcastle, New South Wales, 1895. – Australian National Maritime Museum on The Commons, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 4D: Newcastle Harbour from Fort Scratchley, Newcastle, 1890. Gun in foreground appears to be an RML 80pdr – Ralph Snowball, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

San Francisco

Prior to the opening of the Panama Canal in 1914, ships voyaging to the west coast of America were required to negotiate the notorious Cape Horn, where adverse winds could delay transit for several weeks, and seasonal icebergs were another challenge. None of the project’s Sailing Vessels are recorded as using the Canal, although Panama City on the North Pacific coast was an occasional port of call. Many ports were visited on the western American coast, one being San Francisco adjacent to the iconic Golden Gate bridge opened in 1937 and under which all project vessels would have passed if it had been built, many with export grain cargoes to Europe. Lying on the western edge of San Francisco Bay was a former anchorage named Yerba Buena, and in 1847 this area was changed to San Francisco and development of wharves began followed in 1867 by the start of seawall construction which took several decades before completion including from 1890 a systematic series of switchyards for trains serving the port. The Embarcadero Seawall was built between 1879 and 1916, greatly increasing cargo vessel traffic. The earthquake in 1906 caused fires too and further port development started. Competition from Los Angeles in the 1920’s and containerisation introduced in mid-20th century which led to Oakland on the opposite shore becoming the primary cargo port has seen the demise of San Francisco as a port, but providing tourist attractions of its historical piers.

Figure 5: San Francisco Docks

Fig. 5A: View from Space Shuttle Columbia of San Francisco Bay Area during STS-58 1993 – Jonhson Space Center.National Aeronautic and Space Administration.government/Space Shuttle Earth Observations Photography/Earth From Space/low resolution.

Fig. 5B: A rare 1869 U.S. Coast Survey chart or map of San Francisco Peninsula. – United States Coast Survey, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig 5C: On the wharves, San Francisco, 1900. – National Archives at College Park, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig 5D: Fort Mason wharves construction, San Francisco, 1910 – English: NPGallery, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

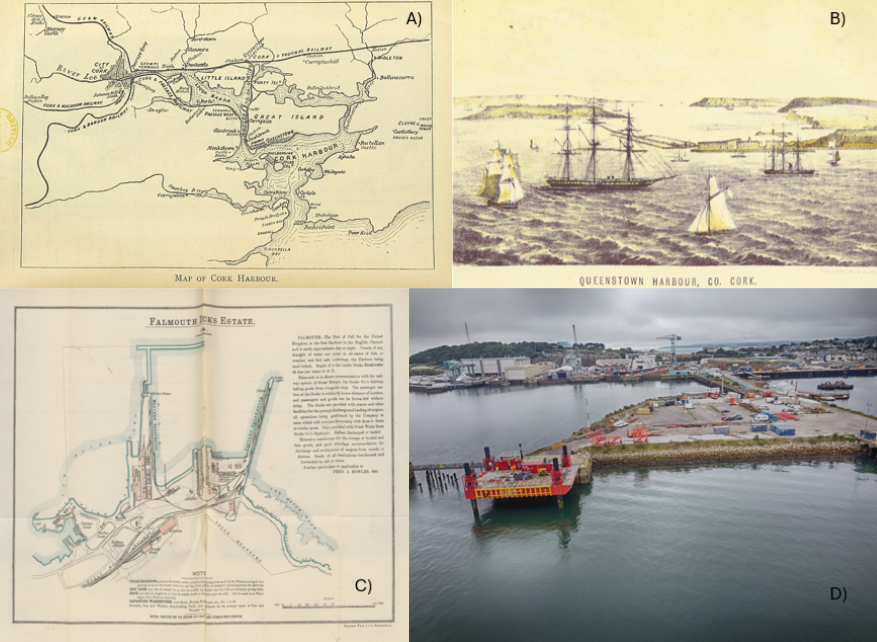

Queenstown or Cork or Cobh and Falmouth

These two ports are included as they were frequent destination “for orders” ports from North and South America, illustrating the then practice of cargo owners sometimes being unsure where their cargoes, often loaded weeks or months previously, would be sold and would ascertain buyers nearer the anticipated time of arrival of the ship, and therefore to which port the ship should be directed.

Cork, on the southeast of Eire, was originally a Royal Navy port from the 1750’s but was changed to Queenstown in 1849 with the visit of Queen Victoria, and then changed to Cobh in 1920 during the Irish War of Independence. Most of the project vessels knew it as Queenstown with its large natural harbour, and it was of course whence the Titanic departed in 1912, the harbour being featured in Figures 6A & 6B.

Figure 6: Queenstown and Falmouth Docks

Fig. 6A: Queenstown and the Places around Cork Harbour. A handy guide, etc. 1895 – The British Library. CC0 1.0

Fig. 6B: Queenstown Harbour, CO. Cork. 1871 – Image extracted from page 307 of The new Hand-Book of Ireland; an illustrated guide for tourists and travellers, by GODKIN, James – and WALKER (John A.). Public Domain.

Fig. 6C: Falmouth – English Channel Ports and the estate of the East and West India Dock Co. … Reprinted from the London “Daily Telegraph”. 1884 – The British Library, No restrictions, via Wikimedia Commons

Fig. 6D: Falmouth Docks by Kernow Skies, 2021 – Kernow Skies, CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Falmouth on the Fal Estuary is the deepest in Europe, the 3rd largest natural harbour in the world, and is sheltered with the Docks on the northern shore of Pendennis Point. A Packet Service to Spain and Portugal started in 1688 alongside cargoes mainly to Mediterranean ports. The Falmouth Docks Company began in 1858 with construction of docks including a graving or dry dock and localised dredging where necessary and connections to the rail system. Dock construction has extended into the mid 1950’s. Twelve of the project’s Sailing Vessels were lost between the Lizard and Falmouth, eight of which were wrecked on the coast.

Tugboats

The first steam tugboat was the Charlotte Dundas in 1803. Steamers of this era were paddle steamers which, if small, were unsuited to the open sea, and although they were built into the 20th century, screw operated tugboats became the norm for towing Sailing Vessels. In the project, nearly every vessel was towed at some point, usually into or out of port and not infrequently considerable distances between ports. Generally, towing was necessary, especially for the large Sailing Vessels, due to adverse winds but often the big “French Cape Horners” having delivered cargo to UK, Ireland or Europe were towed with a small skeleton crew to a French port prior to their next long distance voyage. Towing to a port for repairs was also necessary consequent on storm damage. Modern tugboats are reasonably compact but the late 19th century screw powered tugboats were quite long and these were iron or steel-hulled to withstand towing stresses, such as Figure 7.