MAT is delighted to be taking forward a project assessing the remains of Metal hulled sailing vessels within English Territorial Waters. Thanks to funding from Historic England we are exploring the history and significance of these vessels. Volunteers are involved in undertaking this research. We hear from Jack Thorode, a Masters Student from Southampton University, who spent his professional placement with us researching two of these vessels.

A period of rapid change

During the 19th century, along with practically all elements of life, the ships of Europe underwent rapid change. The industrial revolution enabled coal-mining, iron-smelting, then steel-working on scales incomparable to anything previously. In the 15th century, western countries had adopted the three-masted square sail rig for their oceangoing vessels and despite subtle changes, the basic form of ships remained static for centuries. Then from the first decades of the 19th century, iron ships were launched from British yards and soon after in 1837 the first sea-going steamer: the Rainbow. The Royal Navy gives a good example of how quickly technology changed. The first metal-hulled warship, HMS Warrior, was launched in 1860, a year after their last wooden warship, HMS Victoria. Then in 1871 came the first warship that carried no sail, HMS Devastation (fig. 1). In a very short time the size of naval and merchant vessels, the speed they could travel and inventions such as radio transformed the maritime world into one far more recognisable to what we see today.

Figure 1: Royal Navy warships show the speed of technological change.

1.A : HMS Victoria (1859), Wikicommons.

1.B: HMS Warrior (1860), Wikicommons.

1.C: HMS Devastation (1871), Wikicommons.

Iron hulls and steam engines had made their appearance together and after inventions such as the expansion engine, screw propulsion and the Suez Canal, the engine eventually sealed the fate of many sailing routes. Nevertheless, sailing ships evolved alongside their self-propelled cousins in this period and contributed in important ways to the changing face of the 19th century. Longer steam passenger services required their routes to be supplied with fuel by sailing colliers, and more remote trade routes such as the guano trade from Chile was operated by sailing ships into the early 20th century. Particularly for Britain, metal-hulled sailing vessels represented an important development in the economy of the empire.

Economic significance

Maritime trade was the backbone of the British empire. In the first half of the 19th century, ever increasing demands for emigration and imports of Australian wool, Chinese tea or American tobacco was supplied by British-owned vessels only. However, after the repeal of the Navigation Laws in 1849 this monopoly was lost.

Having innovated industrial processes, Britian was ahead of its rivals in metal production. As a country very resource-rich in coal and iron, yet by then extremely poor in timber, iron-hulled clippers helped British shipyards keep up with new American competition. Additionally, iron-hulled ships weigh less than a third of a similar timber vessel (steel hulls are lighter by 15% still). This is due to a simplicity of structural integrity. Beyond a certain length any sea-going vessel risks being broken in two by heavy seas. This had been overcome previously by heavy diagonal framing but with a price paid in weight and therefore agility and speed. Due to the greater strength of iron, longer yet lighter hulls became possible and greater sail could be carried on iron masts and spars before dangerous strain was put on the structure.

Ships with increased capacity, decreased voyage times and an ability to weather heavier seas were instrumental for the British to overcome the challenges of an evolving world in the 19th century. Any time of rapid change produces unique objects from technological dead ends or links in the chain which are rapidly outdated by their successors. Warrior was decommissioned 1883, having gone from cutting-edge to obsolete in just 23 years. Although perhaps not as dramatic, the form of the metal-hulled sailing vessel was a relatively short-lived product of technological evolution which is an often-overlooked feature of the British Empire.

The Metal Hulled Sailing Vessels Project

The Metal Hulled Sailing Vessels (MHSV) project is examining the potential and significance of the archaeological remains of these sites within English Territorial waters. Research is taking a similar approach to that used for the previous MAT project with a guided pro-forma system – Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War:

The projects share a focus on vessels which are often overshadowed by their contemporaries as well. As much information as possible is gathered about a specific vessel from a large range of online sources. When possible discrepancies are cleared up, and information is presented in a clear and standardised record form. The types of information gathered includes structural details as well as the ship’s career and the crew, including any loss of life. By telling the stories of their construction, voyages and their disasters, we can establish contact with the human element of an important mercantile tradition which built our modern world. We can learn about their lives and empathise with them while recording and making easily accessible information for future researchers.

Charlwood

The vessel I was first tasked with researching, SV Charlwood, is a three-masted barque, 60 metres in length and 10 metres in breadth. It was launched in 1877 and performed many voyages between Europe and South America, it was during one of these voyages in 1891 when disaster struck. About twenty kilometres south of Plymouth Charlwood was struck amidships by the steamer Boston. It was a mighty collision. Charlwood was almost split in two and the situation was exacerbated by the fact that the ship foundered so quickly that the lifeboat was still in the process of boarding when it was capsized by its davits. It was half past 4 in the morning during a dark October night with a strong easterly breeze, the bitter cold doesn’t bear thinking about. Fifteen of the twenty-two onboard lost their lives including the Captain, his wife and his son. The remainder, including the captains 13-year-old daughter, were saved by boats lowered by the Boston and a passing schooner, the Albion.

When researching for Charlwood I was able to go straight to the archaeology itself, all thanks to the work of the dive group Plymouth Sound Divers. Their website and dive reports were perfect for getting acquainted with the physical remains as they are today and provided invaluable information on the condition of the site as well as brilliant photographs of structural elements and cargo. You can view the images here.

Kate Thomas

This vessel shares many similarities with Charlwood. They were both built by Doxford W. and Sons in Sunderland, registered in Liverpool, and foundered after a collision, in this case with 19 lives lost. They are structurally similar also, although Kate Thomas has four masts instead of three and is correspondingly longer, at almost 80 metres (fig 2.).

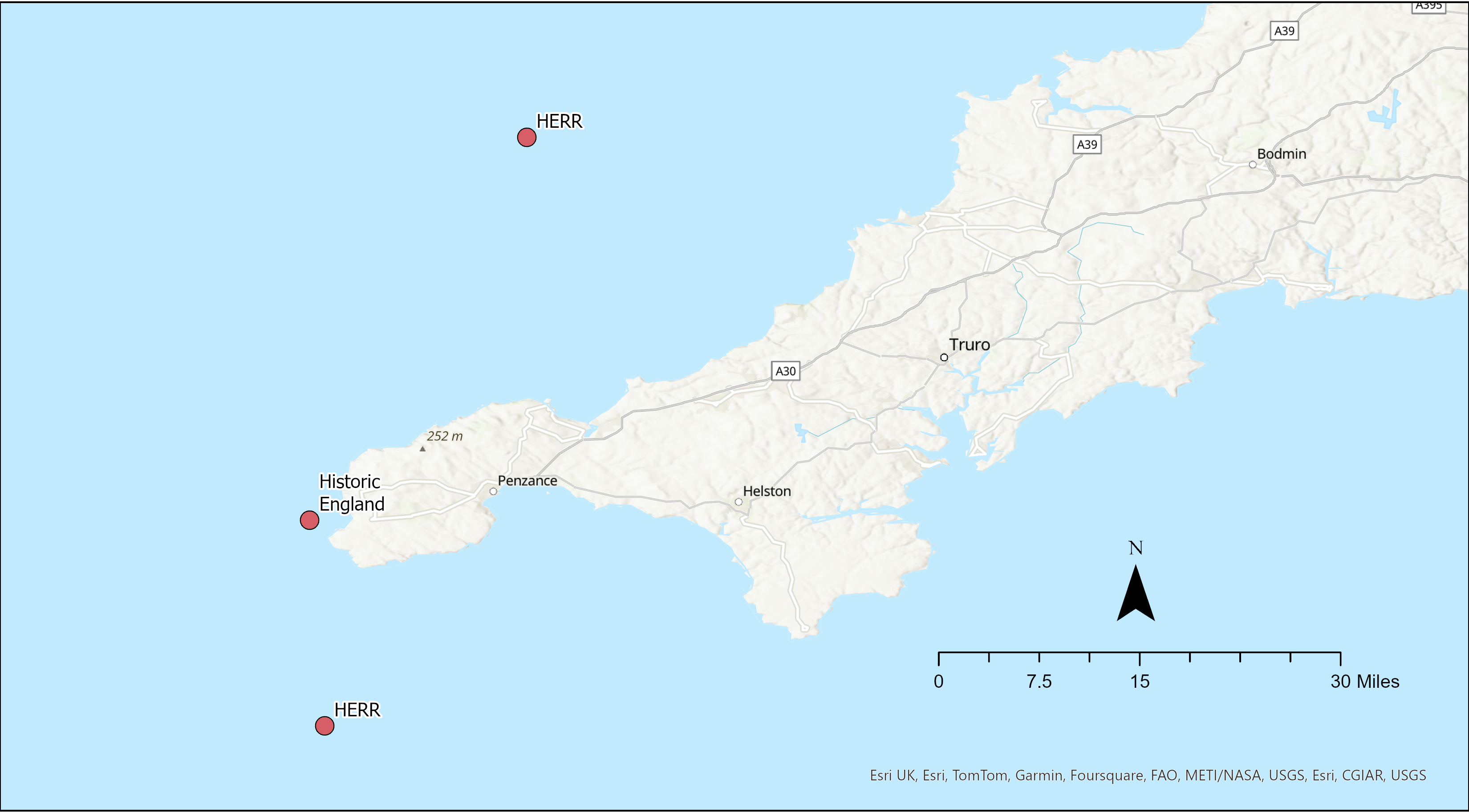

The first problem I encountered when researching Kate Thomas is a perfect example of the more pragmatic aim of the MHSV project: to clear up discrepancies. In this case the discrepancy is a pretty substantial one – the location of the wreck. Authorities on the location conflict to a considerable degree (see fig. 3). Descriptions of the wrecking event sometimes point to the northern most location, sometimes to just off Land’s End. While some claim to have found a wreck in the latter location with a magnetometer signature that would be given by Kate Thomas, Royal Navy divers have searched the area without success. In the absence of any positive identification of a site (for example through the recovery of a ship’s bell as is the case for Charlwood) the problem may remain unresolved for now.

Figure 2: Kate Thomas (launched 1885), Source: Wikicommons

Figure 3: Authorities conflict over the location of the wreck of Kate Thomas. The UKHO and Historic England gives co-ordinates 50.087417, -5.735417, whilst the HERR actually have two other possible locations on record for the site.

The future

One of the most important qualities of humankind is the ability to learn from the past to influence our future. In the quest for net-zero carbon, the shipping industry is one of the most challenging sectors. Many avenues for reducing emissions are being explored and one is a return to the metal sailing ship, albeit in a far more modern form than the traditional rigs of the 19th century.

By keeping in touch with our past, particularly during a time when we had changed the way we live so significantly, we stand a far better chance of learning from our ancestors to help make informed decisions for descendants.

Further Reading

Here you may read about one of the earliest radio stations used for communication to ships: https://maritimearchaeologytrust.org/the-lizard-wireless-station/