In the late 19th Century, many physicists in Europe, America and elsewhere were investigating and experimenting with radio waves. One of these was the Italian, Guglielmo Marconi, who came to England at a young age. He went on to found the Marconi company, which established the Lizard Wireless Station in 1900. There, he conducted further experiments and transmissions to prove that radio waves can travel around the curvature of the Earth. Thus, this small wireless station was at the forefront of the emerging technology. Volunteer John Davies delves into the Lizard Wireless station, and how it revolutionised communications with ships. You can learn more about wireless stations in our booklet First World War Wireless Stations of the South Coast of England, created as part of our Forgotten Wrecks of the First World War project.

Guglielmo Marconi, the man

Guglielmo Marconi was born on 25th April 1874 in Bologna, Italy, into a wealthy family, with his mother being of Irish descent. He was mainly educated at home and later developed an interest in science and electricity. He then studied at the Livorno Technical Institute, working on radio waves, based on earlier works by Heinrich Hertz and Oliver Lodge.

He realised that radio waves could be used as a form of communication when it was not possible to use a land-line wire, such as signalling to ships at sea and between ships. He approached the Italian Navy to progress his ideas, but was turned down. With his mother’s British connections, he decided to move to England in1895, at the age of 21.

Figure 1: Guglielmo Marconi

Source: Wikicommons

He continued his experiments and testing such that in 1897 he was granted his first Patent on wireless technology. In 1899, he founded the Marconi Maritime Telegraph Company in London. His further work is discussed below, but in 1909 he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physics, shared with Karl Braun.

During the First World War, he joined the Italian Navy and worked on their communications. After that, he developed his ideas further, sending short wave signals to his beloved yacht Elettra in the Cape Verde Islands in 1923 and off Lebanon the following year. He passed away on 20th July 1937 in Rome.

Establishment of his companies

His first company was not financially successful, mainly due to the difficulty in persuading shipping companies and the like to take up his ideas. He joined forces with his cousin, Jameson Davis, in 1897 to found The Wireless Telegraph and Signal Company. They carried out experiment and test transmissions, achieving a range of 66 miles (106 Km) by the end of 1899. However, the financial results were still poor.

In February 1900, the company re-organised and changed its name to Marconi’s Wireless Telegraph Company Limited. A new Managing Director, Major S. Flood Page, was appointed.

For many years, Marconi had thought that wireless communications would be very important to shipping. At this time, the end of the 19th century, vessels could only communicate with the shore or other ships by means of flags or semaphore, which needed clear lines of sight. Thus, Marconi and Flood Page felt that this would be their future and set up The Marconi International Marine Communication Company Limited in April 1900. This company, MIMCo, was to put equipment and operators on board merchant vessels and charge fees for their service.

In addition, it would be necessary to have shore stations, to send messages between passing ships and their owners in London or elsewhere. Eight shore stations were to be set up at prominent coastal locations around the UK, including St. Catherine’s Point on the Isle of Wight and on the Lizard Peninsula in Cornwall.

Setting up the Lizard Wireless Station

In order to find a suitable site, Marconi and Flood Page went down to Cornwall in August 1900 and stayed at The Housel Bay Hotel, which was south east of the Lizard village. About half a mile to the east of the hotel was the Lloyds Signal Station, which communicated with ships by flags run up a mast.

The local landowner was Viscount Clifden and he was approached by Flood Page to lease to MIMCo “ a plot of land in the wheat field adjoining the hotel”. The signal station would comprise a small building for the apparatus and suitable masts, sited near Bass Point.

Figure 2: Lizard Wireless Station

Source: Petewotton, Wikicommons

A local builder, George & Sons, dismantled a Great Western Railway hut at Lizard village and re-erected it at Bass Point. Even today, there is still a cupboard inside the hut with GWR on its hinges. The size of this timber building was 33ft x 11ft (10m x 3.3m), with four rooms. The wooden mast was brought from Dovercourt in Essex, in three sections 60ft (18.3m) long, which was then erected to form a mast 150ft (45.7m) high, with numerous guy wires.

Marconi and his team then began installing the apparatus, as shown in Figure 3. Later, a second building was put up at the western end, as a store room.

Testing and Transmissions

On 18th January 1901, the team began testing the equipment. Marconi arrived on 23rd January, having made arrangements that the station at St. Catherine’s Point would send morse signals on that date. The transmissions and receipt of the signals at the Lizard Wireless Station were successful. The distance the signals travelled was 196 miles (315 km) – more than twice the previous one.

However, this feat was not made public until 11th February that year. Later, Marconi referred to this as his “first little miracle”. This success spurred Marconi on in his quest to transmit a signal across the Atlantic. To achieve this, his company began building a much larger station at Poldhu on Angrouse Cliff, north of Mullion.

After 23rd January, the Lizard station received signals from several ports along the south coast of England and also from northern France. The Lizard station’s call sign was LD (Poldhu’s was PD) and testing showed that its daytime range was about 50 miles (80 km) and up to 100 miles (160 km) at night. This was adequate to communicate with passing ships out of sight of land. A few years later, the call sign was changed to MLD, due to the proliferation of new stations needing call signs.

The wireless equipment in the Lizard station

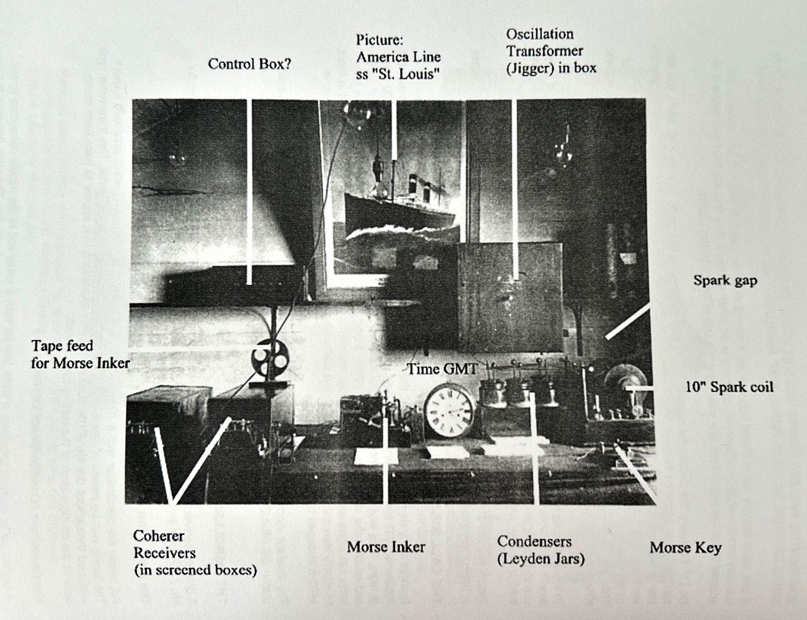

There were several items of apparatus installed on or above a desk in the building. These are shown in the photograph and are as follows:

Figure 3: Apparatus in the hut

Source: The history of the Lizard Wireless Telegraph Station or Marconi’s “First Little Miracle”, David H. Barlow

The Transmitter – a 10inch (25cm) induction coil and interuptor to produce a spark. Capacitors and a transformer were used for tuning, before the signal was fed to the aerial.

The Capacitors – these were Leyden Jars, each comprising a large cylindrical glass jar coated inside and out with foil. The inner layer was connected to a central metal rod, whilst the glass acted as a dielectric. Six of these jars stood in a wooden tray and the outer layers of them was connected by a brass strip. Initially, all six jars were connected in parallel to a “plain aerial”.

To increase the frequency, only three of the Leyden Jars were used in circuit and a primitive form of tuning was used. This was an aerial transformer, known as a “jigger”, where the inner rods formed the “hot”, or aerial, side and the outer foils were connected to earth.

The Aerial Transformer or Jigger – this formed the inductance side of tuning the transmitter. The primary windings were on a fixed board and the secondary ones were on a slider. By moving the slider, the ratio between the two could be varied. The secondary coil had a number of tappings to alter the turns ratio.

The Coherer Receiver – this piece of equipment was to receive incoming signals. It comprised a small glass vacuum tube loosely filled with granules of nickel (90%) and silver (5%), with silver plugs at each end and connecting wires. An incoming signal would make the particles “cohere”, thus forming a circuit between the two plugs. However, the grains then needed to be separated, ready to receive the next part of the signal. Marconi invented a vibrating mechanism to do this.

The coherer operated on a relay, which caused a morse inker to work. The coherers were not consistent in performance because that depended upon the tightness (or otherwise) of the packing of the granules. They were superseded in 1902 with a magnetic detector and multiple tuner.

In common with other coast stations, the Lizard station would keep a listening watch on 500 kHz.

The Morse Inker – A paper tape was pulled through the inker by a clockwork mechanism and a pen marked the incoming Morse signal onto it. The operator would then transcribe this into English text.

Earthing – this was achieved by setting about ten steel plates 6ft x 3ft (1.8m x 0.9m) into the ground around the hut.

Electrical Power – Power was generated by a 1.25 HP oil engine and a 0.5 kW dynamo in one room, feeding the accumulators in the next room. These were sixteen large cells of the Chloride type.

Later developments

Soon after the Lizard Wireless Station became operational, Marconi began constructing a much larger station at Poldhu. That was located at Angrouse Cliff, north of Mullion on the Lizard. This was to be the station that sent the famous Morse “S” to St. Johns in Newfoundland on 12th December, 1901.

The Lizard station was used in the testing of the output from the Poldhu station, whose call sign was PD. Further testing was also done on the use of variable capacitors.

A Royal Visit

In July 1903. The Prince and Princess of Wales, later King George V and Queen Mary, visited the Poldhu Station, then travelled down to the Housel Bay Hotel for lunch. After that, they walked the cliffs and saw the Lizard Wireless Station.

Take over by the General Post Office

During the early years of the 20th century, there was a considerable increase in wireless traffic at all the coast stations and the Post Office saw that this would be the future. In autumn 1909, it took over most of the Marconi coast stations, although the Lizard kept its Marconi operators to maintain communications with shipping in the English Channel. These operators also continued carrying out experiments for the Marconi company. The call sign was changed to GLD.

Emergency call “SOS”

The Lizard Wireless Station was the first one to receive an SOS call, on 18th April 1910 at 12.52a.m.. This was from an American freighter, SS Minnehaha, which lost her way in thick fog and became stuck on Seal Rock, Bryher, Isles of Scilly.

Last Days

Lizard Wireless Station closed in 1913, after a new station opened at St. Just, named Lands End Radio. This took over the GLD call sign.

Modern Times

In 1996, the National Trust took over the site and restored the buildings. The transmission and receiving equipment was re-constructed for public display. This is open during the summer, usually12 – 3pm, run by volunteers.

The other, western building has been converted into a holiday cottage.

Conclusion

The Lizard Wireless Station made significant contributions to the development of wireless communications, thus leading eventually to today’s modern systems of broadcasting, radar, the internet and mobile phones.

Acknowledgements

The History of the Lizard Wireless Telegraph Station, by David H. Barlow

The Institute of Engineering and Technology

Radiomuseum.org

The National Trust