MAT volunteer, Roger Burns, recounts the remarkable history of Steam Trawler Quail, including its involvement in the international 1904 Dogger Bank incident, sinking in the Humber in 1907, unexpected salvage and lengthening, and final sinking in 1915 having been requisitioned by the Admiralty as a minesweeper.

The Steam Trawler (ST) Quail

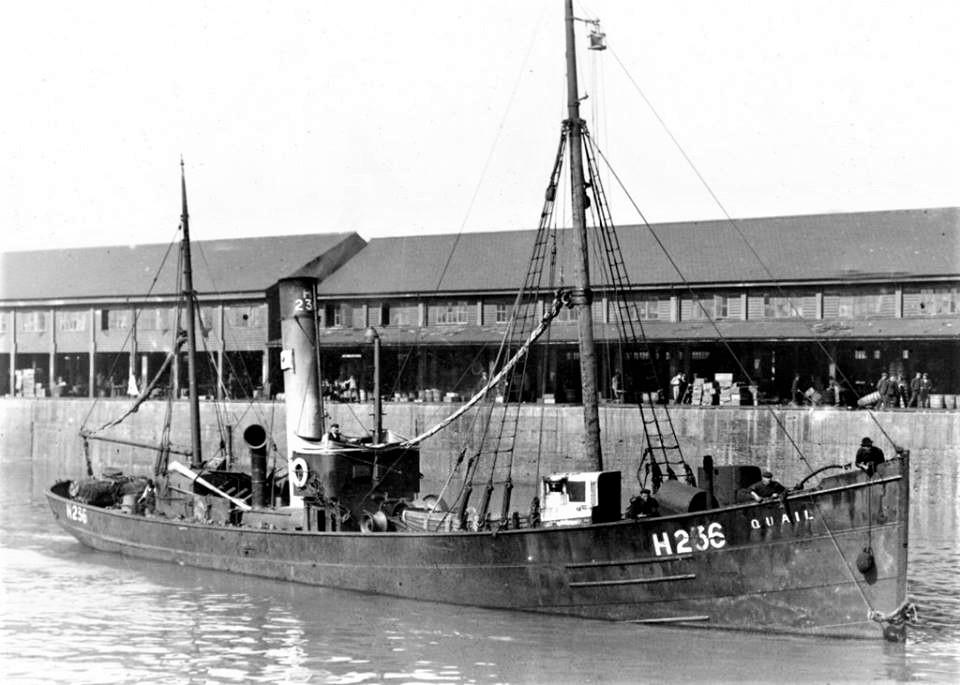

The iron-hulled trawler, ST Quail, was completed in July 1897, having been launched on 16 June 1897 by Edwards Shipbuilding of North Shields for Kelsall Bros & Beeching Ltd., originally of Manchester, but who 11 years later were based in Hull. Quail was driven by a single screw from a triple expansion, single boiler, steam engine of 41 hp built by N.E. Marine Engineering Co Ltd, Sunderland. It was 106 ft (c.32.3m) long, had a 20 ft 6 in (c. 6.25m) beam, an 11 ft (c. 3.35m) deep hold, and was registered with ON108531 at Fleetwood on 23 May 1897 with 144 grt. From 1899 it was registered at Hull as Fleetwood registry closed. As a fishing vessel, Quail was allocated a Fleetwood registration, FD179, between 21 July 1897 and 24 March 1899. This was changed to a Hull registration H236 on 12 April 1899.

An indication of the times and punishments for misdemeanours was illustrated in the Shields Daily News of 2 February 1904, which reported that “the second mate of the trawler Quail, of Hull, was charged with greatly delaying that vessel, after he had signed on to the voyage. Defendant was found in a public house, and efforts were made to induce him to fulfil his engagement, but he absolutely declined. The vessel was detained, with steam up, for fully fourteen hours, and £30 (approx. £3,700 in 2021) expense was incurred by the owners. The defendant was committed to prison for 21 days”.

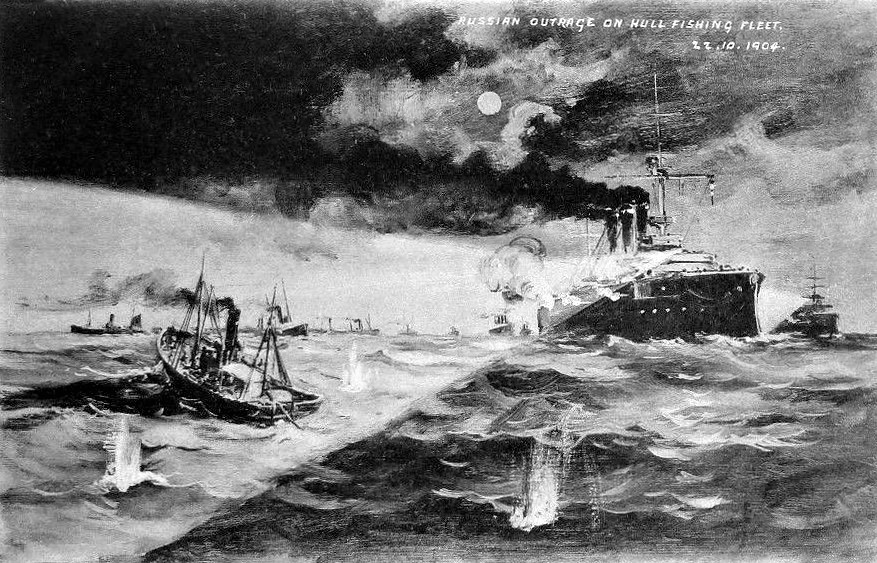

International Dogger Bank Incident

On the night of 21/22 October 1904, Quail was one of 59 trawlers of the Gamecock fleet that were fishing near the Dogger Bank in the North Sea. Unexpectedly, the trawlers came under fire from the second Russian squadron of the Pacific fleet, which was en route to the Far East to reinforce their 1st Pacific Squadron stationed at Port Arthur, and later Vladivostok during the Russo-Japanese War. The squadron, under the command of Admiral Rojdestvensky, had mistaken the trawlers for an Imperial Japanese Navy force.

Quail was not hit but three British fishermen died, a number were wounded, the trawler Crane sank, and five were damaged. In the darkness, confusion abounded, even to the extent of some Russian fire being directed at their own ships. A “No Sound” video of the fleet back in Hull is here. The newspapers referred to the incident as the Dogger Bank Case, and political tensions ran high, which led to an International Commission of Enquiry that reported on 26 February 1905. The fishermen eventually received £66,000 (approx. £8.6m in 2021) from Russia in compensation and a memorial funded by public subscription was erected in Hull in 1906. More on the incident may be read here.

Stranded off Spurn Head then Sunk in the Humber

On 9 December 1906, Quail was stranded on the Middle Binks off Spurn Head at 01.30 and was towed in a disabled condition back to Hull a few hours later by the tug, Humber. The next incident was much more serious, and again the story featured in the newspapers. The Quail had left Hull for the fishing grounds on 19 August 1907 but due to the weather had anchored in the Humber off Killingholme, with most of the crew asleep in their bunks. The Wilson liner SS Dynamo en route from Hull to Antwerp collided with Quail, which sank within 30 minutes. Quail’s skipper, William Richard Lewis, and the third hand, John Nicolini, both lost their lives. Lewis was trapped in his cabin and Nicolini drowned trying to reach the Dynamo, which had saved the seven survivors of Quail’s crew. Both left a widow and young family.

The Globe of 22 August 1907 carried the following report:

‘IMPRISONED IN A SINKING SHIP.

SEAMAN’S THRILLING STORY.

Harry Wiley, the mate of the ill-fated Hull steam trawler Quail, sunk in the Humber after being run into by the Wilson liner Dynamo, was interviewed yesterday by a representative of the ” Daily Mail,” to whom he gave the following account of his thrilling experiences.

“I had turned in about three-quarters of an hour,” he said, “when I was awakened by a violent concussion, which made the vessel tremble from end to end. Before I had scarcely time to realise what was happening, I saw water rushing into the cabin from all sides. My comrades had fled, and I tumbled out of my berth and made for the cabin door as quickly as my legs would carry me. The weight of the water, however, kept it closed. I pulled at it desperately, but I could not move it, and in a very few moments the water had reached my waist, and I got on the cabin table to see if there was any possibility of escaping from my prison by way of the skylight. The water still continued to come in from the sides of the ship, and to save myself from drowning I had to keep standing on the cabin table; but even there I was compelled to stand as erect as possible on my toes, so as to keep the water from getting into my mouth. My head was in the skylight top, where I had only a chance of a mouthful of air. Several of mates, thinking perhaps some of us remained inside, tried to break the iron bars of the skylight, and though I could not signal to them through the thick glass, I could feel the vibration of every blow they struck. Then their hammering ceased. They had given up, and either left the ship to save themselves or come to the conclusion that, with the cabin full of water, those that remained were already drowned. It was a horrible moment when their hammering ceased and I was left there alone.

“I had nearly given up altogether, and once slipped from my foothold, but was fortunately borne again to the surface, where I caught hold of the projecting ledge of the framework. I held on to it for some time like grim death, wondering and watching for what was to happen next. I thought I should never see land again. My heart sank within me, and I was beginning to despair, when I noticed the water began to ebb. We had apparently sunk in shallow water. Down and down it went, and with every inch my hopes grew stronger. I was chilled to the bone, but I held on, and presently was able to again reach the cabin door. By degrees I pulled it inwards—one inch—then two —then three—until it came open wide, and the water rushing out carried me with it in safety to the upper deck. The force of the water was so great that my feet never once touched the steps of the companion-way. The vessel was deserted, but I could see the Wilson liner nearby, and presently they saw me and sent a boat to fetch me, and with my comrades, who had given me up for lost I was taken back to Hull”.’

A few days later, a diver searched for the skipper without success, but his body was later recovered when the vessel was salvaged. In October 1907, a comprehensive Board of Trade report found that “the collision and loss of life were caused by (i) the Quail being anchored in the middle of a particularly dangerous part of the fairway (ii) Her lights being rendered difficult of identification, owing to the bright lights at the new Immingham Dock works (iii) The absence of a vigilant look-out on board the Dynamo”.

The Quail was salvaged as it was causing a danger due to its position. This was the first time this had happened in the Humber. Then, unusually, it was lengthened at Goole by about 3.2m, given a new wheelhouse, and re-registered, with its grt increased from 144 to 162, and the nrt doubled to 61, putting out to sea once more on 10 March 1908.

Shortly afterwards, Clara Ada Nicolini, widow from the collision, with two dependent children, was awarded compensation of £192 11s to 10 April 1908 and £9 14s for funeral expenses (approx. £23,000 and £1,150 respectively in 2021).

Quail’s Final Four Months

In November 1914, ST Quail was hired by the Admiralty, renamed HMT Quail III, armed with 2×3 pounders, allocated a Pennant number of 645, and deployed as a minesweeper as of February 1915 operating out of Portland. Late on 22 June 1915, Quail III collided with the tug Bulldog seven miles SSW of Portland Bill and sank at 23.40. There were no casualties and Quail III came off the register on 11 November 1916 as a total loss.

We hope you have enjoyed reading about the remarkable history of Steam Trawler Quail. Thank you to MAT volunteer, Roger Burns, for your research and dedication in putting this together. Please go to our blog for more fascinating accounts of vessel history and other maritime archaeology topics.