MAT Volunteer Roger Burns has nothing but admiration, not to mention some awe, at the skill, bravery and exploits of the Royal National Life Boat Institution (RNLI). Modern craft are self-righting, advanced vessels of specialised design and construction suited to their intended purpose. But the early craft were sail and oar propelled and volunteers, amazingly, would often need to row through raging seas relying on manpower alone. These rescue missions would often result in the successful rescue of mariners in distress, but sadly, on occasion, volunteers would lose their own lives in the process. Roger takes a look at the tragedy of one such event, the ‘Salcombe Lifeboat Disaster’, when lifeboat William and Emma of Salcombe was called out to the Plymouth schooner Western Lass in 1916.

The RNLI, Saving Lives at Sea

The RNLI has a long history and heritage, having saved over 140,000 lives at sea since 1824. In 1854 its name changed from the National Institution for the Preservation of Life from Shipwreck to the Royal National Lifeboat Institution. Lifesaving, whether of seasoned mariners or holiday makers, has been interspersed with the loss of RNLI volunteers going to the rescue of others in difficulty, most often in challenging conditions. The RNLI volunteers are from many walks of life with understanding employers who are accustomed to their employees dropping whatever they may be doing when their alarm pagers go off. Prior to electronic aids, the Coastguard, as it still is, was a key link in the chain of emergency to the launch of the lifeboat. A list of 19th and 20th century instances where rescuers were lost can be read here. The design of lifeboats has evolved from sail and oars to petrol or diesel-powered craft. The RNLI’s timeline includes information on the development of lifeboats (https://rnli.org/about-us/our-history/timeline), with the William and Emma being an example of a type used in the late 19th and early 20th century.

The Lifeboat William and Emma

William and Emma was launched by Thames Ironworks & Shipbuilding Co. Ltd, Blackwall, London in 1904 for the RNLI. It was 10.67m long with 3.05m beam, sail and oar driven, and weighed 6.25 tons fully laden. It was a ‘Liverpool Type Pulling and Sailing non-self-righting Lifeboat’, manned by 15 crew, of whom 12 were oarsmen, plus the coxswain, second coxswain and bowman. Its sails were jib and two lug sails, shown in Figure 2. William and Emma cost £924, funded through a bequest (approx. £115k in 2020). It had two water ballast tanks and two drop keels, and each oar weighed 25lbs (11.4kg). The port oars were coloured white and the starboard oars were coloured blue – this simplified steering by calling the relevant colour to pull or back off because the rudder was not effective at maximum rowing speed.

The Fate of William and Emma

William and Emma had been called out on 27 October 1916 to render assistance to the Plymouth Schooner Western Lass, which, during a severe storm, had gone ashore and stranded in a sandy cove on Lannacombe beach near Start Point, Devon. Fortunately, the East Prawle Lifesaving Apparatus Company were able to rocket fire a line to the schooner and rescue its crew. Due to a faulty telephone line, this was not known in Salcombe and William and Emma set out with its crew of fifteen local men in a Force 9 gale to attempt a rescue. The crew didn’t learn that their help wasn’t needed until they reached the stranded schooner. They managed to return upwind to Salcombe but on their third attempt to cross the Salcombe Sandbar, they were hit by a massive wave and capsized. It was one of the worst cases in the RNLI’s history. Thirteen of the crew were drowned and only two survived. Having been stranded, the Western Lass was later salvaged and continued trading until 1927 when it again went ashore, this time at Cape Cornwall where it was wrecked without any casualties.

Salcombe Museum includes an excellent portrayal of the Salcombe Lifeboat Disaster, with models, photographs and eyewitness accounts, along with a section of William and Emma’s hull. Information about the disaster can also be found here at page 155, and here.

The BBC website tells a similar story, including information about the challenging tidal conditions at Salcombe Sandbar encountered by William and Emma. The website also includes an image of the ‘Salcombe Lifeboat Disaster’s’ Commemorative Centenary Plaque. More information about the plaque can be found here. Salcombe Museum displays a number of artefacts recovered from the disaster including those depicted in Figures 3 and 4.

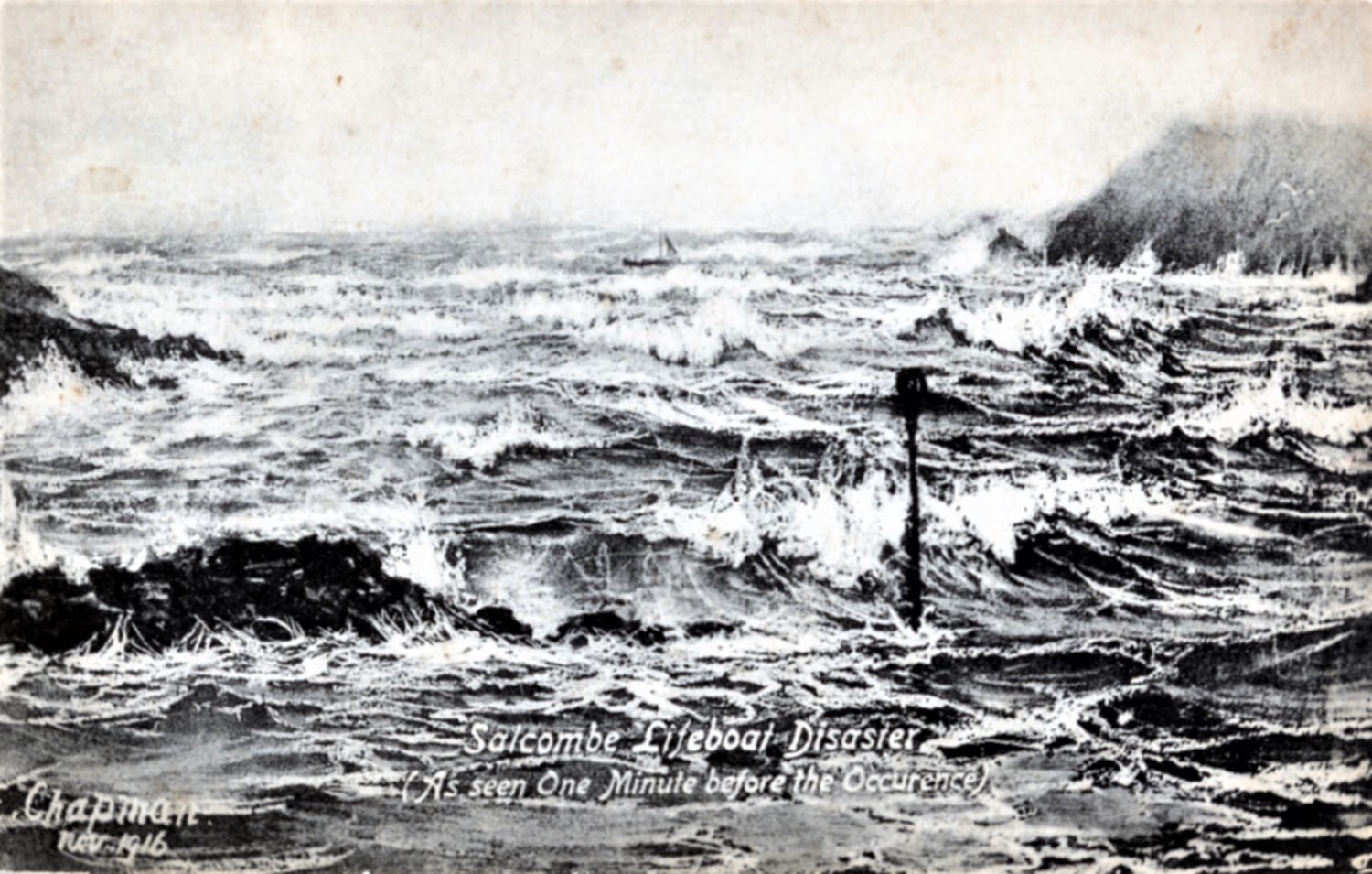

The perilous weather conditions at Salcombe Sandbar at the time of the disaster can be seen in Figure 5. This image is endorsed “Salcombe Lifeboat Disaster (as seen one minute before the Occurrence)” and was apparently taken by local photographer, Edward Chapman.

A detailed and comprehensive Board of Trade Wreck report about the disaster can be read here.

The William and Emma centenary was recorded in a series of YouTube videos. A flotilla of RNLI lifeboats commemorating the disaster can be watched here. There was also a church service, highlights of which can be watched here. The full service can be watched here.

Acknowledgements

MAT appreciates the assistance of Roger Barrett, curator of Salcombe Museum, who agreed to the use of the two museum artefacts in Figures 3 and 4 and confirmed that the Western Lass was salvaged and continued trading.

We hope you enjoyed reading about the tragic story of RNLI Lifeboat William and Emma. To read more fascinating tales, accounts and explorations of maritime history, please visit our blog. You may also like to explore the Shipwreck Centre & Maritime Museum’s blog.