Hallsands village, located in an Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty on the South Devon coast at Start Bay, about I mile north of Start Point, was until the last few years of the 19th century associated with fishing. From 1897 for the next 20 years, it suffered hardship, with its community progressively losing their means of fishing, culminating in losing their houses and belongings to the sea. This was brought about by removal of vast quantities of sand and shingle which had protected the precarious community for many, many decades. The result was that most inhabitants were forced to abandon their houses before they collapsed, but today the village has international renown within the Coastal Engineering fraternity, an example of the effect of coastal dredging when processes are not fully understood.

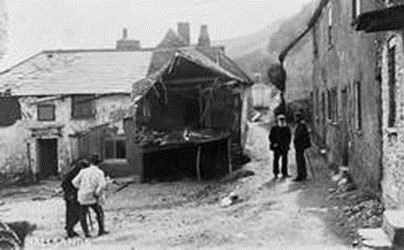

The early history of Hallsands is unknown, but a chapel has existed there since at least 1506. The village was at a cave known as Poke Hole, and probably was not inhabited before 1600. The village [1] grew in size during the 18th and 19th centuries, and by the 1891 census, it was thriving with 37 houses, a spring, a public house called the London Inn dating from 1784 with stables, a bakery, a greengrocer, and a population of 159. The nearest school was a 2 mile walk. Many of the men of Hallsands had other trades to supplement the living they made through fishing, such as tailor, carpenter and blacksmith.

Most residents of Hallsands depended on fishing for a living: crab fishing on the nearby Skerries Bank and seine fishing for mackerel and pilchards. The Leicester Chronicle reported in October 1842 that the “seins belonging to Hallsands secured the immense number of about 800,000 pilchards, which were rather small, fetching from 9d. to 18d. per hundred”. (Approx. £4 to £8 in 2017).

The environment of the village was sometimes harsh. Exposed to the weather and storms, but built on a rocky ledge above sea level and protected by the sand and shingle banks in front of it, the hardship was a way of life. The Devon Sea Fisheries Committee added to the difficulties, by passing bylaws[2] in the mid-1890s curtailing certain kinds of fishing, much to the annoyance of fishermen from Hallsands and the nearby communities of Slapton, Torcross and Beesands. Despite trawl nets being banned, some fishermen continued to use them. The Rev.Conrad Finzell of Stokenham wrote to the Dartmouth and South Hams Chronicle to report that continued trawl fishing had entirely crippled the crab fishermen of Hallsands and Beesands, where over 100 crab pots had been destroyed by nets in a three week period [3].

The Admiralty decided in 1895 that the Royal Navy dockyard at Keyham, Plymouth should be extended to accommodate the increasing size of modern warships. By 1907, Keyham, itself renamed as North Yard and now part of HMNB Devonport, had expanded greatly, requiring vast quantities of sand and gravel for its construction. Sir John Jackson, an established contractor for large scale civil engineering works including docks and harbours won the contract, and turned to a 1,100m stretch of coast off Hallsands for the materials needed, having secured a licence from the Board of Trade for removal of sand, shingle and gravel from below the low water mark in a designated area, without the villagers’ knowledge. The licence contained a clause that if the operation should damage the foreshore defences of the adjacent land, then the licence would be cancelled. Dredging started in April 1897, initially with a bucket-ladder dredger, later replaced by two suction-pump dredgers discharging into 1,100-ton capacity hopper barges for transport to Devonport. Soon afterwards, Sir John Jackson obtained a similar licence from the Office of Woods that permitted the removal of sand and shingle from the foreshore between high and low water marks, again without the knowledge of the villagers. A clause in this agreement stated that the work should be done in such a way that the land above the high-water mark should not be exposed to the encroachment of the sea.

By the end of May 1897, the removal of shingle at an average of 1,600 tons per day had altered the shape and angle of the beach, so much so that the low water mark moved until it was actually further inland than the old high-water mark. A Board of Trade Inquiry[4] was held on 10 June 1897 with reference to a complaint against the dredging made by the local MP, Mr F.B. Midmay, on behalf of the fishermen and villagers who feared that the dredging might destabilise the beach and thereby threaten the village. The inquiry[5] found that the activity was not likely to pose a significant threat to the village, so dredging continued, as the licence was not withdrawn, but Sir John Jackson undertook to pay the fishermen of Hallsands £125 a year while the dredging continued, together with a Christmas gratuity of £20. The payments were intended to compensate for the interference with fishing, not for any damage to the shoreline.

Disquiet continued. Over the next few years, there were more pleas for help, enquiries and damage. In November 1900, the villagers petitioned their MP about damage to the houses. At spring high tide, the sea now came within 1m (3ft.) of the village rather than the 21-24m (70-80ft.) it had been before dredging started. Cracks started to appear in houses at the south end of the village and the sea wall was undermined. Following another Board of Trade inspection, Jackson was ordered to provide new concrete footings to the sea wall and a concrete slipway for the boats, to compensate for the lack of beach.

There followed more damage to the sea walls which were built to protect the houses, and to the houses themselves. After much campaigning and protesting[6] by the villagers and their supporters, on 8 January 1902, the licence[7] to dredge was revoked. After nearly 5 years of dredging, around 650,000 tonnes of shingle were removed from the beach. In the years that followed, especially 1903, some houses suffered further damage, including the London Inn, which lost the kitchen, a bedroom and the cellars. In 1903, John Masefield wrote prophetically about the eventual demise of Hallsands in a poem[8].

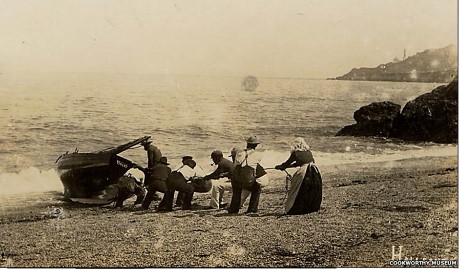

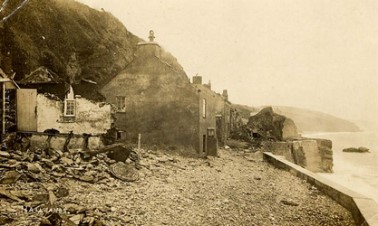

A new stronger sea wall was put in place in 1906 to protect the remaining 25 cottages and their 93 inhabitants. Although these numbers fell to 79, the sea wall contributed to the villagers’ feeling of security but this was shattered in a violent storm[9] which started on 26 January 1917. The fishermen, expecting worsening gales, storms and a high tide, hauled the boats high up in to the village street and battened them down. The children were evacuated to the Mildmay Cottages. At 8pm spring tides brought huge waves which crashed into the houses at roof height and destroyed the buildings behind the sea walls from above. The houses built on the empty chasms in the ledge collapsed and those on the rocks were battered by wind, waves and stones. The villagers feared for their lives.

By midnight, four houses were totally demolished and none survived intact. Amazingly, all 79 villagers survived and scrambled to safety during a lull in the storm at low tide. Dawn on 27th January revealed a devastating picture, and the sea was strewn with timber and broken furniture. The sea walls had held, otherwise many more houses, and possibly lives, would have been lost. It was likely that the next high tide would destroy all that remained so with the wind still raging, villagers worked to salvage what they could. On 28th January 1917, with the next high tide, the walls broke and the village was destroyed. Only one house remained in any way habitable, the highest in the village, that of the Prettyjohn family.

The Kingsbridge Gazette that day led with the headline ‘The beach went to Devonport and the cottages went to the sea’.

On 25 September 1917, The Board of Trade held an enquiry[10][11] at Hallsands, on the order of the Devon Sea Fisheries Committee, on behalf of the inhabitants of Hallsands, for compensation in respect to the damage recently sustained by the village from the sea. The Committee urged that compensation should be made to the sufferers out of national funds, and adequate protection afforded, but it would be impossible to construct the houses where they once were. A civil engineer, R Handsford Worth, conducted extensive survey of the coastline with respect to the dredging, and his work was often quoted at this and other Public Inquiries of the day for Hallsands.

Many families, having lost everything, relocated to neighbouring villages North Hallsands and Beesands to fight the long battle for compensation[12] which took seven years! This delay is encompassed in an article “The day the Sea came down the Chimney”[13] which relates the following:

In 1918 the Government appointed an inspector for a local inquiry. His conclusions were unequivocal: the dredging had caused the collapse. He recommended compensation of £10,500 (approx. £0.55m in 2017) to rebuild the village on safer ground. The civil servants were not impressed. The Assistant Secretary to the Treasury wrote:

“If we offer [a grant] at once we shall only be pressed for more – the Hallsands fishermen, as past history shows, are past masters in squeezing. One sympathises with them in the disaster which has overtaken them but a year or more has now elapsed and it is probable that by now they have managed to get homes and a livelihood.”

In fact, most of them were still living nearby, renting rooms, overcrowding the homes of their neighbours or even sleeping in the ruins.

Embarrassed by its findings, the Government refused to release the report until, sometime after the Second World War, it was passed with other documents to the Public Records Office, where it has remained unnoticed for half a century.

In May 1918, a lower payment of £6,000 (approx. £0.3m in 2017) was made as a “full and final settlement” of all claims. As inflation reduced its value, the committee administering the grant tried in vain to access the new funds allocated for council housing. In August 1922, they were forced to admit defeat, and work began on a development of just ten houses, which still stand today in the ‘new’ village of North Hallsands. The remaining money was insufficient even to pay for these, so the former homeowners were forced to borrow and pay rent for the rest of their lives.

Only one house was left standing on 27 January 1917, on the road leading down to the village. It was owned by Elizabeth Prettyjohn who stubbornly refused to leave, and lived there with her chickens until her death in 1964, aged about 80 years. She acted as a guide to visitors who came over the years, curious to see the remains of the village. Today her house is used as a summer holiday home.

Another famous Hallsands resident was Ella Trout and her sisters Patience, Clara and Edith. When their fisherman father, William, became sick, Patience and then Ella gave up school and operated his boat which was the only source of income for the family. William died in 1910 when Ella was 15 years old. On the 8th of September 1917, after the Hallsands disaster, Ella was out in the boat crab fishing with her 10-year-old cousin William, when they saw the SS Newholm struck by a naval mine one mile south of Start Point. Along with William Stone, another fisherman in the vicinity, they rowed to the scene and helped rescue nine men. In recognition of her bravery, she received the Order of the British Empire. The sisters, with compensation for the destruction of their cottage at Hallsands and their own earnings, built Trout’s Hotel on the cliff above the deserted village. The Trouts ran the hotel successfully until 1959.

Another poem[14], by Susan Wicks, was written about Hallsands and published in 2003.

In 2006, the world premiere of an opera[15], Whirlwinds, based on Hallsands was presented at Gateshead.

A viewing platform[16] overlooking Hallsands, was erected by South Hams District Council and signage is incorporated into the South West Coast Path. In May 2012, it was reported that a 200 tonne, 10 m-long section of coastal cliff had collapsed damaging a stone barn and threatening the stability of the popular cliff-top viewing platform. Whilst this was a relatively small failure by national standards, the inhabitants of the two remaining houses in the village were evacuated amid fears that the access route to these houses would be undermined. As a result of the damage to property, the need for evacuation measures and a well-documented history of coastal erosion in the area, the BGS Landslide Response Team visited the site to assess the landslide. The viewing platform was subsequently reopened, declared safe.

In 2015 the campaign for commemoration of Hallsands at 100 years received the backing of Blur frontman Damon Albarn[1], who had owned a property in Hallsands for 15 years and who credited the village with inspiring his successful Gorillaz album Plastic Beach, which was released in 2010.

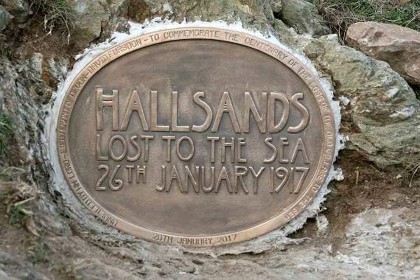

In January 2017, a 100-year memorial[17][18][19][20] was held and a plaque was erected.

Geology and Coastal Engineering

During the dredging and after, a civil engineer, R Handsford Worth, conducted extensive survey of the coastline with respect to the dredging, and his work was often quoted at Public Inquiries of the day. Hallsands has become internationally one of the world’s best known coastal erosion sites due to the circumstances of the loss of the village, and is an exemplar of the effect of coastal dredging when processes are not fully understood.

It should be noted that the storm of 1917 was particularly destructive due to the gale direction, north easterly, and the offshore Skerries Bank during north easterly winds was of primary importance creating wave energy impacting on Hallsands stretch of coast.

Sir John Jackson.

Throughout the saga, Sir John Jackson had apparently provided funds under the terms of his contract, but these were regarded as insufficient based on the damage created by the dredging. He owned, apart from his contracting operation, Westminster Shipping Company. In 1918, Sir John Jackson’s luck finally ran out. A parliamentary inquiry[22] found him guilty of overcharging the nation on war contracts. He resigned from parliament in disgrace and died a year later.

Researched and writtern by Maritime Archaeology Trust Volunteer Roger Burns.